- India

- International

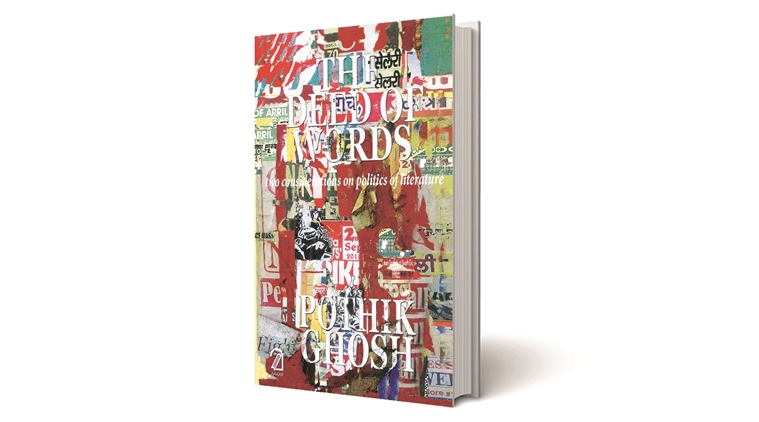

Left to Write

What is the politics of literature? A critical study of two Indian writers attempts to answer.

Name: The Deed of Words: Two Considerations on Politics of Literature

Author: Pothik Ghosh

Publisher: Aakar Books

Pages: 143

Price: Rs 450

If a writer is involved in a political movement, do these two roles, that of a writer and an activist, inhabit her as “two indispensable alterities” of her indivisible and “individual self”? Or do they “co-exist” “separately” “within the same individual, and thus in no apparent relation with each other”? In The Deed of Words, a critical study of the works of the Bangladeshi writer, Akhtaruzzaman Elias, and the Hindi writer, Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh, Pothik Ghosh explores a fundamental question — what is the politics and use, if any, of literature?

Both Elias and Muktibodh were avowedly Leftist, as Ghosh examines their works through the prism of Alain Badiou’s concept of subtraction. The French philosopher is among the most prominent figures in the last few decades to have argued for the revival of communism.

Ghosh charts his course by making a series of assertions about art. At first, he states that a writer’s love for literature and her engagement with radical political movements lead to “separated” and “non-relational coexistence” of these two selves. He then argues that the terms of reference should not be the “use of art for politics”, but the “use of politics in art”. Such a method, he proposes, introduces novelty in art, what Badiou elsewhere termed “subtraction” and explained by citing the works of Paolo Pasolini.

Ghosh’s rigour in building his argument is remarkable, his scholarship impeccable. For that alone, this slim book

deserves serious consideration. Yet, it is difficult to agree with his contention that “poetry becomes political not by being a poetry of politics”, or “poetry for politics”, but “only when it tends to be poetry in politics”.

If politics is an intervention in the affairs of the world, art, in itself, is a political act. The moment someone

decides to express her anguish or love, even hatred, in a poem or a novel, that marks a political mediation, even a protest. It could assume an almost imperceptible form, but an artistic expression amounts to an inestimable intervention in human affairs.

Similarly, an artist need not be separated from the activist within. Contrarily, these two “selves” feed and nourish each other. By arguing for an essential political self of a writer, the radical Ghosh legitimizes almost the similar contention of the right wing when it had denounced all the writers who had returned their awards last year. The right termed these writers “anti-national”, refusing to accept that the act of writing can be inherently political, and returning the awards is its inevitable corollary. The left and the right rarely accords the sovereign space literature demands by virtue of just being literature. They wish it to be a means to some greater end, whereas a piece of art could be an end in itself.

In furtherance of his praise for Muktibodh’s “historicity”, Ghosh targets the Hindi literature’s Nayi Kahani (New

story) movement and terms it a “self-enclosed world of static strangeness and unfamiliarity”. That’s an erroneous claim that has been repeated by several Leftist critics before Ghosh. It ignores that the Nayi Kahani brought into focus the alienated Indian, who had found her sense of time and space being appropriated by colonial forces, whose self was fragmented beyond recognition. This movement was as much a registration of a historical fact, as Muktibodh’s angst-driven poems were. Generations of critics have juxtaposed Muktibodh with other Hindi writers, in an attempt to establish the former’s artistic superiority on the basis of his social concerns. In another continent, and in a not-so-dissimilar context, Marxist critic Georg Lukacs tried to assert Thomas Mann as being greater than Franz Kafka. The verdict of history has been obvious.

Badiou elsewhere said that the “world is made not of law and order, but of law and desire”. In art, desire takes myriad hues. A critic, more than an artist, is expected to identify and chart out the constitution of this desire.

More Lifestyle

Apr 26: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05