The Satanic Temple is in a battle with the state of Florida. Last holiday season, the Department of Management Services, an arm of the state government, allowed religious groups to construct displays of faith in the central rotunda of Florida’s infamous Capitol Building. First a Christian group erected a nativity scene that endorsed Christianity. Then an atheist group hung a winter solstice banner celebrating the Bill of Rights and freedom from religion. Inspired, another atheist built a Festivus pole made of beer cans, and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster added a small pile of holy noodles to the capitol’s halls.

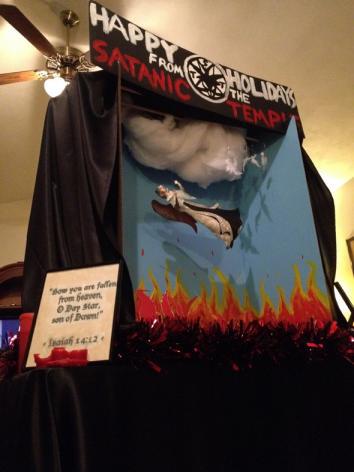

Under current First Amendment law, the capitol had no ability to turn down any of these groups; once the government opened the door to one religion, it had to let them all in. But when the Satanic Temple applied to erect a display featuring an angel falling into a pit of fire, officials turned it down. The display, they explained, was “grossly offensive during the holiday season,” and was barred from display in the capitol. Now, with Christmas around the corner, the temple is reapplying, asserting its constitutional right to include its display alongside the others. And this time, it’s bringing a legal team.

How did the Florida Capitol, the symbol of the state’s exceedingly conservative governor and legislature, become the center of a constitutional showdown launched by Satanists? Surprisingly, the fault lies squarely with the Supreme Court’s most conservative justices. In their quest to let the government endorse and sponsor mainstream religion, they accidentally granted groups like the Pastafarians a constitutional right to force the government to advertise their beliefs.

The seeds of the current Satanist showdown were planted in 1984, when the city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, argued that it had a right to fund blatantly religious Christmas displays using taxpayer money. Five conservatives on the Supreme Court agreed, holding that the First Amendment (which bars the government from making any laws “respecting an establishment of religion”) did not forbid the city from financing religious displays. Writing for the court, Chief Justice Warren Burger ruled that the image of Christ in a manger was merely a “celebration of a public holiday with traditional symbols” and thus served “legitimate secular purposes.” (When the dissenting justices pointed out that the court had placed deeply holy figures on the same spiritual level as “Santa’s house or reindeer,” Burger scoffed, “Of course this is not true.” He did not elaborate further on his reasoning.)

Five years later, a similar issue reared its head after the city of Pittsburgh placed religious displays—including a Hanukkah menorah and a nativity scene—in the Allegheny County Courthouse. A badly splintered court ruled that the nativity scene endorsed Christianity in violation of the Establishment Clause, because an angel held a banner that proclaimed “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” (“Glory to God in the Highest”). The majority was also troubled by the scale of the nativity display; it was placed on the “grand staircase” of the courthouse, lending the impression that the city held it in special esteem. Six members of the court, however, ruled that the menorah didn’t unconstitutionally endorse religion. Placed outside the courthouse, next to a Christmas tree and a sign saluting liberty, the menorah was, in the eyes of the court, merely a celebration of “the winter-holiday season, which has attained a secular status in our society.”

The implicit message of the Allegheny case was that cities can allow, and even finance, religious displays on government property—as long as the city doesn’t appear to be favoring one religion over another. In most cities, these rulings have led to an all-comers policy; if officials permit every applicant to construct a religious display, after all, they can hardly be accused to preferring a specific religion. For a while, the policy was tacit and loose. Most cities probably assumed that they retained the ultimate right to refuse a religious display that strayed too far from their sense of decency.

Photo by Doug Mesner.

But then the Supreme Court stripped that right from them—in another ruling that was initially billed as a conservative victory. The case, Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, dealt with a student who wanted UVA to give him money to print Christian magazines. The state university refused, insisting that its own rules forbade it from funding sectarian publications. But the five conservatives on the Supreme Court ruled that UVA’s decision violated the Christian student’s free speech rights. Once UVA decided to start funding student publications, such as newspapers and magazines, the court held, it had to fund all publications, regardless of the content.

Rosenberger was a complicated case, but the upshot was simple: If the state opens a forum for a certain category of expression, it doesn’t get to choose who can express themselves or how they get to do it. Even if that expression conveys offensive ideas in an odious manner, the state can’t censor it.

When Rosenberger first came down, many liberals bemoaned it as a loophole through which Christians could obtain more government funding. It may well be—but it’s also the Satanic Temple’s best shot at getting its display in the Florida Capitol. State officials claim that, because they were generous enough to open up the space to religious groups in the first place, they retain the final authority over who gets to display what. Rosenberger says: absolutely not. If officials didn’t want the Satanic Temple erecting a display in the capitol rotunda, they shouldn’t have let religious groups in in the first place. Now that they’ve opened the gates, they have no right to stop the stampede.

So far, the Satanic Temple hasn’t heard back from state officials, though it filed its application—and a legal notice from its counsel, Americans United for the Separation of Church and State—in October. On Nov. 6, Americans United sent a follow-up letter, informing the state that if the temple’s application wasn’t answered by Friday, Nov. 14, it will consider the application to have been denied. The application went unanswered, and so the temple, aided by Americans United, is preparing a lawsuit against the state for a violation of the temple’s First Amendment rights. Under the current constitutional regime, the temple appears to have a slam-dunk case.

At that point, Florida might like to argue that the temple’s quest is really just a ruse, a ploy to bring attention to the absurdity of state-sponsored religion. But the state will be barred by Supreme Court precedent from making such an argument—thanks, once again, to a conservative ruling. In the recent Hobby Lobby case, the court considered the claims of Christians who said they believed that IUDs cause abortions, even though they emphatically do not. The court’s five conservatives refused to even consider the plaintiffs’ sincerity, simply taking it on faith that their protestations were genuine. This credulity sets an interesting precedent and puts the court in something of a bind: It would look terribly unjust for the justices to trust Christian plaintiffs while skeptically interrogating non-Christians. With Hobby Lobby, the court may have inadvertently stripped itself of the ability to question plaintiffs’ beliefs whatsoever—unless the justices want to flagrantly favor Christian plaintiffs.

Under this set of conservative precedents, the fiercely Republican state government in Florida has essentially no legal argument against the Satanic Temple—or the Pastafarians, or any other professedly religious group that wants to tout its faith with a display in the state capitol. (In our post–Hobby Lobby legal landscape, even secular humanism is considered a religion, because secular humanists say it is.) The Supreme Court was supposed to guard the wall of separation between church and state. Instead, reactionary justices helped to tear it down.