Censorship of the Internet in China is a heavily studied but little-understood process, driven by both private networks and government employees and having effects that are hard to measure. To better understand it, a group of researchers tested censors and filters by attempting to post over a thousand bits of content on various social networking sites. They found that there was an aggressive pre-filtering process that holds a high number of submissions for review before they're posted—and that the results are actually undermining China's censorship mission. The filters tend to hamstring pro-government content as often as they block anti-government writing.

Part of the authors' process involved setting up a social media site of their own within China to see what standards they would be subjected to and what tools they would have to use in order to comply with the country's censorship requirements. They found that sites have an option to install automated review tools with a broad range of filter criteria. Censorship technology is decentralized, they wrote, which is a technique for "[promoting] innovation" in China.

Most research that has been done on Chinese censorship is largely based on what posts exist on the Internet at one point and then do not at a later time, indicating that they were pulled by censors. While that behavior is easily observed, there is another layer to the censorship system whereby users' posts get held for review by censors before they're made public. This new study attempted to figure out what sort of posts would get held for review, what would eventually make it through, and what might escape suspicion at either the posting or review stage, only to be removed later.

For the experiment, the authors created two plant accounts at each of 100 Chinese social media sites, including heavyweights like Sina Weibo and Sohu Weibo. The accounts posted about a variety of current events, such as a mother who "self-immolated to protest China's repressive policies over Tibet." All of the posts were written by native Chinese speakers and were based on existing posts, both ones that were eventually censored as well as ones that were able to stay online.

The posts were categorized in two ways: content that mentioned collective action (for instance, "corruption") or not, and posts that were pro- or anti-government. After creating the posts, researchers monitored them to see which of five paths they took through the Chinese censorship system. The posts could be published immediately and stay online; they could be published but later removed manually by a censor; they could be held for review and then allowed after a censor's approval; or they could be held for review on publication and never posted if a censor found them too problematic. An account could also be blocked from posting again after a publication attempt. In total, the team submitted 1,200 posts across the various social media networks.

After monitoring the posts, the authors found that 66 of the 100 social media sites used some kind of automatic filter that would quarantine posts based on their content or user profile for review. Forty percent of the 1,200 posts received that treatment. "Of those submissions that go into review, 63 percent never appear on the web," the authors wrote.

This means that out of 1,200 submissions, there would be about 302 posts (around 25 percent) that an outside observer would never have known were subjected to censorship—the only parties who know about them were the poster and the censors. More generally, between 20 and 40 percent more posts that were trying to incite collective action were censored than those that were not attempting to incite, regardless of the topic they were discussing.

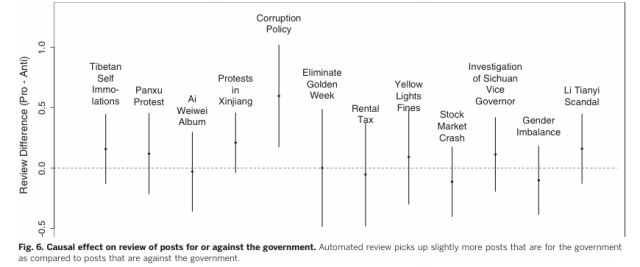

The most significant findings about the automated review tools that most sites use, though, concerned how bad they were at helping the censorship cause. "If there exists a nonzero relationship here, it is that submissions in favor of the government are reviewed more often than those against the government," the authors wrote. "Not only is automated review conducted by only a subset of websites and largely ineffective at detecting posts related to collective action events, it also can backfire by delaying the publication of pro-government material. "

One example of this phenomenon could be seen in posts about President Xi Jinping's December 2013 visit to a certain steamed-bun shop in Beijing—a typically innocuous event. Eighteen percent of posts about the visit that were critical of Xi were censored, compared to 14 percent of posts that were favorable and 21 percent of posts that just described the event. The overaggressive filtering was caused by the fact that pro-government posts are just as likely to include language about collective action as anti-government ones, triggering a review and slowing down that wonderful establishment-positive prose from spreading across the Internet.

The authors also experimented with posting about a variety of events to see if they could feel out what types of talk or items would trigger the filters. They found that posts about corruption, posts that included specific names of Chinese leaders, and posts about organizing action either on the Internet or "on the ground outside the Chinese mainland" (e.g. "Demonstration," "go on the streets") were hit the hardest. But again, the effect was just as heavy on pro-government as anti-government posts.

While the study can't see absolutely everything that Chinese censors might have touched—a post that was not automatically filtered and was then manually reviewed and left alone would have escaped notice—it brings to light a normally obscured layer of the opaque censorship process. If the Chinese government is interested in promoting innovation in censorship tools, it appears that software that doesn't muffle the government's biggest proponents is an area that's ripe for disruption.

Science, 2014. DOI: 10.1126/science.1251722

Reader Comments (37)

View comments on forumLoading comments...