How Better Relations With Cuba Might Affect American Baseball

Two months after President Obama announced plans to restore diplomatic ties, an MLB official mentioned the possibility of holding spring-training games in Cuba.

Sunday marks the start of the Major League Baseball's spring training, in which the league's 30 teams play a month's worth of exhibition games to determine the composition of their final rosters. All of this year's games will be played in Florida and Arizona, as is the case every year. Soon, however, spring training might expand to a surprising destination: Cuba.

Speaking to reporters on Saturday, MLB Player's Association chief Tony Clark divulged that the league considered holding exhibition games in the island nation this year before ultimately deciding against it. “I will say to you it is conceivable somewhere down the road that there may be a spring training game played in Cuba, but it is hard to tell at this point in time," Clark said.

The statement comes just two months after President Obama announced that the U.S. would seek to normalize ties with Cuba. And while this process will not occur overnight—the two countries have not yet established embassies in their respective capitals—the coming rapprochement between Cuba and the United States will have a pronounced effect on the sport of baseball.

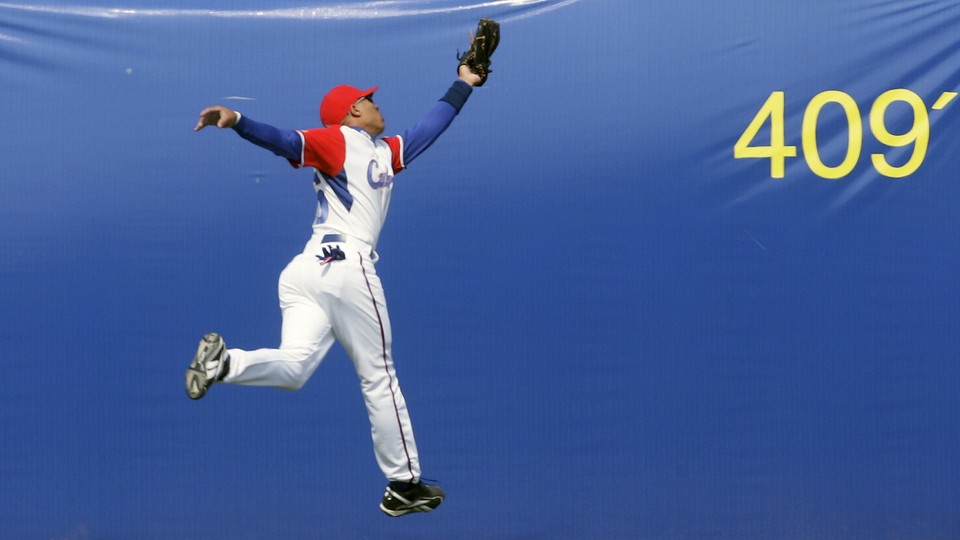

Cuba is no stranger to the game. Baseball arrived on the island in the 1860s, right around the time American leagues began to professionalize, and by the early 20th century Cuban leagues were regarded as the peers of those in the United States. And, unlike Major League Baseball, Cuban leagues permitted racial integration. According to historian Roberto Gonzalez Echevarria, the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers chose to hold spring training in Havana in part because Jackie Robinson, baseball's first black player, had encountered so much racism in Florida.

This cultural exchange ended abruptly in 1961, when the U.S. imposed a trade embargo on Cuba. Since then, the two countries have played baseball in almost complete isolation from each other. Nearly all of the Cuban players who have played in the major leagues since then were forced to defect from their homeland, occasionally in harrowing circumstances—Yasiel Puig, a Dodgers outfielder who defected in 2012, endured extortion at the hands of people smugglers. Last year, a total of 19 players from Cuba appeared on major league rosters—a group that includes stars like Yasiel Puig, Jose Abreu, and Jose Fernandez—at the beginning of spring training. (The Dominican Republic and Venezuela accounted for 83 and 59, respectively, of the MLB's 853 players.)

Should normalization proceed without interruption, it's easy to imagine that one day, Cubans will be as numerous on Major League rosters as players from the Dominican Republic and Venezuela are now. That day, for logistical as well as ideological reasons, is a ways off. But even baby steps—like potential regular spring training games in Havana—have generated a lot of excitement.

"There is intrigue," said Clark. "There is interest. I'm very interested to see what happens here."