What Would Mark Twain Have Thought of Common Core Testing?

In his autobiography and in Tom Sawyer, the author skewered the test-centered teaching of his day. It's not hard to imagine what he would have thought about an exam that grades student essays via computer.

I've been teaching high school English in Illinois for over 20 years, but have only recently come to believe that I am complicit in a fraud. For nearly a decade, I have dutifully prepared college-bound students for the rigors of the ACT and the Advanced Placement (AP) English Literature and Composition exam. Even though I believe there's an undue emphasis on testing in our current school culture, I have considered this preparation an important part of my job because these tests are important to my students both academically and financially. But I question what, if anything, the new Common Core test—which will include writing components graded in part by computer algorithms—will have to offer my students.

I am not alone in my skepticism about the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) exam, which rolls out next year. Criticism has come from the left, led by Diane Ravitch, a former assistant U.S. secretary of education who has become one of Common Core's most vehement opponents. Conservative pundits like Glenn Beck have railed against it, too. Even Louis C.K. has an informed opinion.

My kids used to love math. Now it makes them cry. Thanks standardized testing and common core!

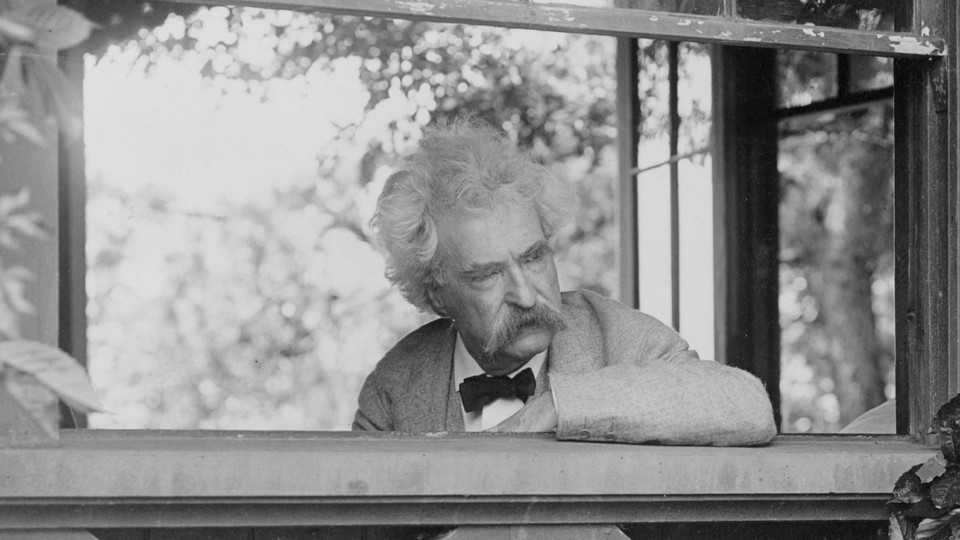

— Louis C.K. (@louisck) April 28, 2014It's not hard to guess what another great American satirist would have had to say about the Common Core curriculum. Mark Twain had an abiding concern with education, and he treated formal schooling derisively in his writings. His 1917 autobiography describes his education in the mid-19th century, at the dawn of the public school movement; his acerbic portrayal of Mr. Dobbins in the school scenes of Tom Sawyer is based on Twain’s remembrances of his own teachers and experiences. In one scene, set on Examination Day, Twain mocks the vacuous nature of writing instruction as he shows Tom Sawyer's classmates reading their essays aloud: “A prevalent feature in these compositions was a nursed and petted melancholy; another was a wasteful and opulent gush of ‘fine language’; another was a tendency to lug in by the ears particularly prized words and phrases until they were worn entirely out.” The examinations come to an abrupt halt when Tom and his friends hide in the garret, lower a cat on a string, and watch it snatch the wig off the teacher's head.

In 1887, Twain penned an introduction to English as She is Taught, a parody of sorts written by a Brooklyn school teacher who had crafted together her students’ most outlandish and misinformed answers. Twain quotes his favorite passages: “The captain eliminated a bullet through the man’s heart. You should take caution and be precarious. The supercilious girl acted with vicissitude when the perennial time came.” His real target isn't the writing itself but the school system that gave rise to such disjointed answers. "Isn't it reasonably possible," he asks, "that in our schools many of the questions in all studies are several miles ahead of where the pupil is?—that he is set to struggle with things that are ludicrously beyond his present reach, hopelessly beyond his present strength?" He notes, for example, that the date 1492 has been drilled into every student's memory. In the book's essays, it "is always at hand, always deliverable at a moment's notice. But the Fact that belongs with it? That is quite another matter."

Ten years later, in Following the Equator, Twain compared the instructional methods in American asylums for the “deaf and dumb and blind children” to those used routinely in Indian universities and American public schools. As a friend of Helen Keller and a champion of her education, Twain was familiar with the methods of asylums; he'd convinced his friend H.H. Rogers to finance her schooling at Radcliffe in 1896. In Following the Equator, he chastises public schools for emphasizing rote learning and teaching “things, not the meaning of them.” He applauds the “rational” and student-centered methods of the asylums, where the teacher “exactly measures the child’s capacity” and “tasks keep pace with the child’s progress, they don’t jump miles and leagues ahead of it by irrational caprice and land in vacancy—according to the average public-school plan.” In contrast, Twain quips, “In Brooklyn, as in India, they examine a pupil, and when they find out he doesn’t know anything, they put him into literature, or geometry, or astronomy, or government, or something like that, so that he can properly display the assification of the whole system.”

The Common Core standards and their assessment tools would have given Twain plenty of fodder for his sardonic wit. The first “anchor standard” for writing at the grade 11–12 level declares that students will “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” This goal will be assessed by Pearson, one of America's three largest textbook publishers and test-assessment companies. Pearson will, at least in part, be using the automated scoring systems of Educational Testing Services (ETS), proprietor of the e-Rater, which can “grade” 16,000 essays in a mere 20 minutes.

Les Perelman, a retired M.I.T professor, has earned a reputation for exposing the flaws of what he calls "robo-grading." In an April interview with The New York Times, he claimed that ETS privileges “length and the presence of pretentious language” at the expense of truth, stating, “E-Rater doesn’t care if you say the War of 1812 started in 1945.” He watched the e-Rater return high scores after he submitted nonsensical passages—for instance, the claim that “the average teaching assistant makes six times as much money as college presidents ... In addition, they often receive a plethora of extra benefits such as private jets, vacations in the south seas, starring roles in motion pictures.” These sentences hardly adhere to the stated goal of “valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence” of claims. Perelman observes, “Once you understand e-Rater’s biases … it’s not hard to raise your test score.” Tom Sawyer's classmates would have quickly figured out how to game this system—just as they gained favor with Mr. Dobbins by parroting “prized words and phrases” in their Examination Day essays.

Twain would also likely have been suspicious of the profit motives behind the new scoring system. PARCC's contract with Pearson, awarded earlier this year, could be worth more than $1 billion over the next eight years, according to a recent Politico article. In a quote in a May Politico story, John Cohen, president of American Institutes of Research (AIR), argued that the contract seemed to have been designed specifically for Pearson: By the time the bidding began, Pearson had already been working on the first year of the project, and the company was the lone bidder on the lucrative contract. The business deal also came shortly after Pearson had announced a major collaboration with Microsoft—a fact that prompted Diane Ravitch to insist, in a recent Huffington Post article, that "[Gates's] role and the role of the U.S. Department of Education in drafting and coercing almost every state to adopt the Common Core standards should be investigated by Congress."

Twain was fascinated by technology, and was thought to be the first author to submit a typewritten manuscript for publication, in 1882. He was also wary of the business interests that often propel new products. At the end of the 19th century, he was lured into investing in the Paige Compositor—an intricate automated typesetting machine that promised to revolutionize the publishing industry at a time when type was still laboriously set by hand. (Think the Victorian Period’s potential equivalent of the word processor.)

By some accounts, Twain poured $200,000 into backing the machine and its inventor, James W. Paige. The scheme nearly ruined him financially, and the invention never panned out, in spite of Paige’s many pleas, promises, and repeated requests for more cash. The 2010 released edition of Twain's autobiography includes this startling remark about Paige: “If I had his nuts in a steel-trap I would shut out all human succor and watch that trap till he died.”

Twain’s frustration with Paige seemed to influence A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court: The protagonist, a 19th century industrialist named Hank Morgan, lands in Arthurian England and comes up with a scheme to modernize Camelot's military. He deceives Arthur and obfuscates the wizard Merlin. The end result is disaster: 25,000 royal subjects die after Morgan constructs an electric fence and Gatling guns using 19th century technology that none of them, including Morgan, can operate responsibly.

As Twain found out at great personal expense, the mere promise of progress is insufficient when the stakes are high. In the case of the Common Core standards, what's at stake is the future of America's students, teachers, and entire public education system. At the very least, Twain might have joined the push for greater transparency in testing methods. As M.I.T.'s Perelman put it in an April Boston Globe column, after he was denied access to Pearson's scoring system, “even toasters have more oversight than high stakes educational tests.”

In Twain's writings, he returned again and again to a simple theme: Education should be practical and meaningful. When high marks on exams are the goal, students end up focusing on isolated facts and writing in what Twain described in Tom Sawyer as a "wasteful and opulent gush." He would have almost certainly had something to say about essay-grading software and corporations that refuse to reveal their testing methods. With so little transparency, and with so many dollars and futures at stake, Twain might have condemned an “assification of the whole system” that wields its technology as recklessly as Hank Morgan infiltrated Camelot.