FKT Up? Kilian Jornet’s Insane New Sport

With warp-speed ascents that include the Matterhorn (1:56) and Denali (9:43), ultrarunner turned alpinist Kilian Jornet Burgada is the king of the endurance world's latest obsession: fastest known times. And now he plans to run up Everest.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

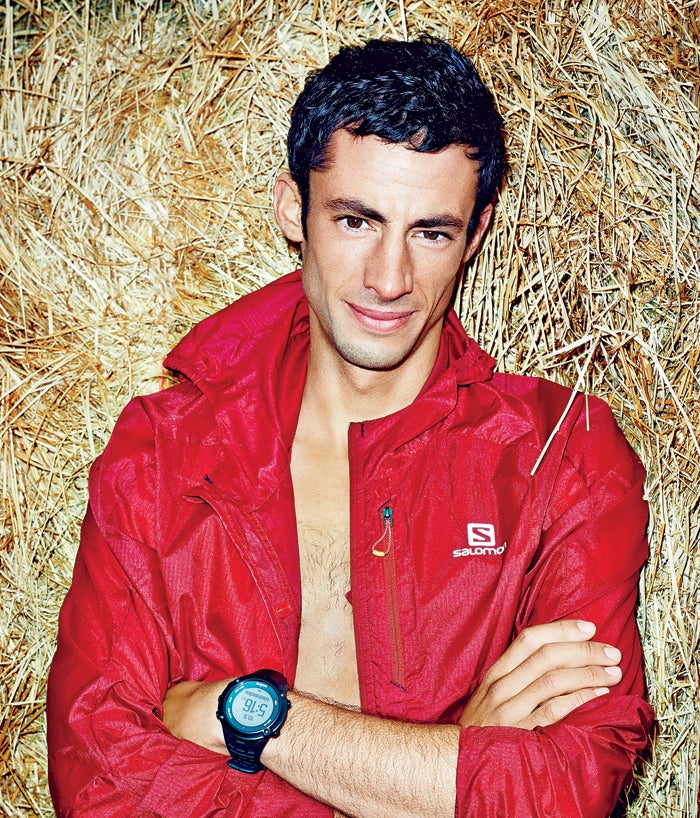

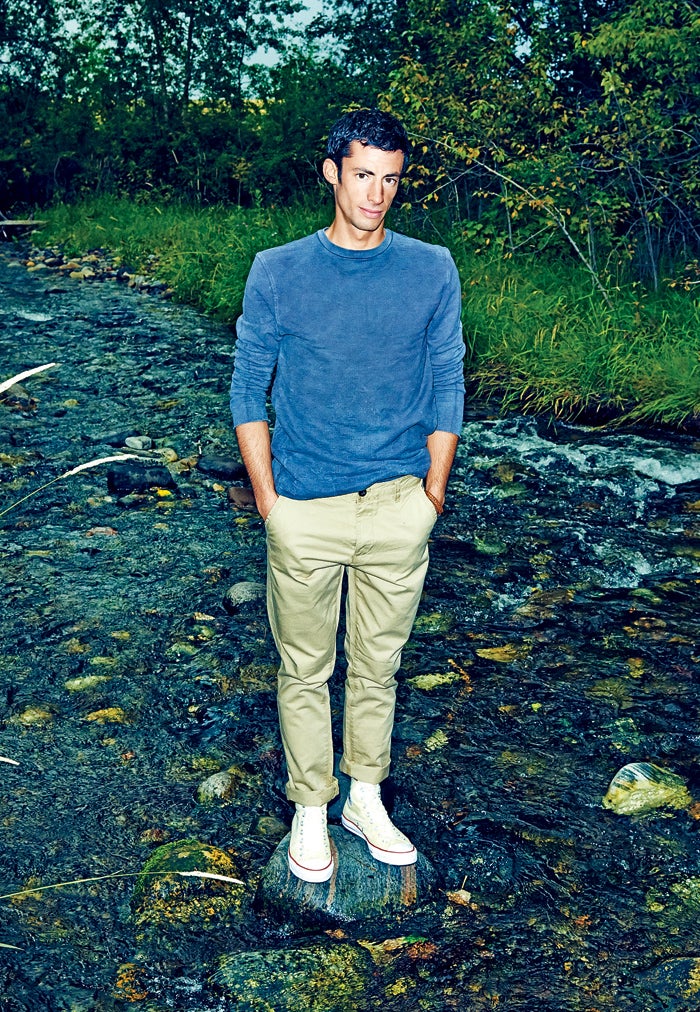

If you think it’s scary to race Kilian Jornet Burgada, the 27-year-old Spanish ultrarunning beast, try dating him.

One September morning in 2013, Jornet set off for a light and fast climb in the French Alps with his girlfriend, 27-year-old Swedish trail runner Emelie Forsberg. To her competitors, Forsberg sort of is Jornet. She’s gorgeous and charming and superstrong, and like him she arrived as a young nobody and now reigns alongside him as a world champion and frequent event winner in the Skyrunner World Series, a collection of some of the hardest mountain races on the planet. She’s also a world-class ski mountaineer, but when she joined Jornet for that morning run, Forsberg got a taste of something new—fear.

After hours of scrambling in little more than running shoes and technical pants up the Frendo Spur, a classic mountaineering route ascending icy 50-degree pitches above Chamonix, France, heavy weather set in just below the summit. They lost time searching for the right route, causing Forsberg to struggle. “I became so cold, and I couldn’t focus my thoughts very well,” she recalls. “I was stressed and felt trapped.” They called for help, and a pissed-off rescue team rappelled down and got them to safety. “I’m very angry when I see the continued rise of sneakers despite our requests,” the rescue chief fumed. “Mountain practice must be undertaken with adequate equipment.”

Jornet was grateful for the help, but he has made a habit of ignoring such warnings. In 2012, he was inches away from his idol—Stéphane Brosse, the legendary French ski mountaineer—when Brosse fell to his death as the pair attempted a speed crossing of the Mont Blanc massif. Jornet bounced back from that tragedy by going even higher, lighter, and faster. He recruited another Frenchman, Mathéo Jacquemoud, for a speed attempt up and down Mont Blanc in the summer of 2013, but this time his partner suffered minor injuries when he fell into a small crevasse on the descent. Unable to keep the pace, Jacquemoud told Jornet to race on alone, and Jornet still broke the record. A month later, a solo Jornet bagged another: round-tripping the Matterhorn in less than three hours. In June of 2014, he raised the stakes again, setting off alone in falling snow and racing up and down Denali—a climb that typically takes two weeks—with an ultralight ski-mountaineering setup. He finished in 11 hours 48 minutes, nearly five hours faster than the previous mark.

All of it—the meagerly equipped assaults on expedition-size peaks, the close calls with close friends, the thrill of microsecond choices on crumbly shale atop fall-and-you-die ridges—has positioned Jornet as the breakout star in a movement most people don’t even know exists but will be hearing a lot about soon: FKTs. Fastest known times.

FKTs have no rules, no schedules, and often no witnesses. You pick a spot, you pick your moment, and you go. No waiting around for race day, no packet pickup or starting waves, just the challenge of blitzing down a classic trail or inventing your way through rarely traveled wilderness as fast as you can. Since Jornet set the speed record on Kilimanjaro in 2010 (7 hours 14 minutes round-trip), seeking FKTs on iconic trails and peaks has become de rigueur among ultra-endurance athletes as an exercise in cred building. FKTs seem like a new idea, but they’re really a throwback to the glory days when all the sport’s races were just a glimmer in an enduro freak’s eye. Before there was Western States, there was Gordy Ainsleigh wondering if he could run 100 miles as fast as a horse. Before there was Badwater, there was Al Arnold setting out alone to see if he could jog 146 miles across Death Valley in 130-degree heat.

Jornet relies on his own body fat for fuel. During his almost 12-hour Denali circuit last June, he consumed a half-liter of water and a single energy gel.

FKTs don’t win you Olympic medals or official recognition. In most cases, no one will know or care if you set a new one—no one except you and your friends, those fellow believers who scamper all night into the wet, buggy, coffeeless woods to hand you a burrito as you flash by in the dark. When ultrarunner Jenn Shelton’s partner bailed halfway through last summer’s bid for an FKT on the 223-mile John Muir Trail, Shelton was startled to come around a bend and find Scott Jurek waiting. The elder statesman of ultrarunning had gotten word that she and her partner were struggling, so he grabbed his gear and bolted into Yosemite to pace her home. She finished in four days and nine hours, good for second-fastest female and a lifelong bond of respect. “One of the worst nights of my life, spent with one of the best motherfuckers I know,” Shelton later tweeted.

Expect the growing FKT movement to shed its scrappy, unpublicized existence next spring. That’s when Jornet will head to Mount Everest without oxygen, carrying only the slimmest survivalist’s pack of food, water, and protective gear, and attempt to lay down a new record on the world’s most scrutinized peak. Jornet hasn’t settled on his precise route or starting point yet, but he does have a time in mind: 20-some hours up, 35-ish back down. Bottom to top to bottom in one weekend.

Jornet’s emergence as a crossover star in the high-risk sport of alpinism comes as little surprise to anyone paying mild attention to trail running over the past decade. He’s been Sky Running world champ six of the past seven years while also dominating the most prestigious ultra races—Western States 100, Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc—and more than a dozen smaller muscle flexers, including the Pikes Peak Marathon and the World Championship of Ski Mountaineering. During his debut at last summer’s Hardrock 100, considered America’s toughest ultrarunning course, he threw back a midrace tequila shot and dillydallied at an aid station because he was lonely and wanted the second-place runner to catch up and keep him company. Socializing complete, he surged off to crush the course record by 40 minutes.

You can retire with a trophy case like that, but Jornet insists he’s still apprenticing. He has no coach or specific training plan, preferring instead to disappear into the mountains every day for seven or eight hours, usually alone but often stopping to quiz random hikers and climbers about approaches and conditions. “It’s important to keep your ears open,” he tells me during a Skype call from his summer base in Chamonix. “You need to be humble.” And humbled, as he was during the rescue with Forsberg. “This sport is about improving, not winning,” he explains. “You never learn from victory.”

Already, his trial and error approach has given him the most daunting and versatile skill set in endurance sports. Take his chainring: while growing up in the Pyrenees as the son of a mountain guide, Jornet developed different gaits for different types of terrain. On steep climbs, when everyone else is walking, Jornet straightens his back and downshifts to a pitter-patter that look like he’s running in place. In fact, he’s using elastic recoil from rubbery leg tendons to get extra uphill bounce.

Additional findings from the Jornet lab:

Fat is your friend. He was one of the first ultra-runners to reduce his calorie intake on long outings, relying instead on body fat for a more dependable, nearly inexhaustible fuel source. During his almost 12-hour Denali circuit, he consumed a half-liter of water and a single energy gel.

Cross-training helps you cross over. Unlike many burnout-prone ultrarunners, Jornet does much more than log endless miles on trails. He skis all winter, runs all summer, and climbs in between. He’s as comfortable on skins as he is on ropes, as quick with an ice ax as he is on switchbacks. Changing things up opens his eyes to new techniques. Ski mountaineering, he discovered, translates to raw foot speed: “You build leg strength, so you can take longer steps running downhill.”

For focus, add fun. Jornet competes nearly every week of the year—25 races on skis, 15 on foot—which forces him to stay sharp and in the moment. But the more he races, the more joyful he gets: in his first Western States, Jornet was going head-to-head with the two favorites when he leaped off a rock and clicked his heels like Fred Astaire. “Was that on purpose?” I ask. He laughs. “Yes, you have to make some fun. What we do isn’t serious.”

“That’s something I’ve got to learn from him,” says Dakota Jones, a 24-year-old Colorado trail-running savant who joined the rare league of Jornet beaters in 2012 by passing him to win the 45-mile Transvulcania. “The week before Hardrock, he ran like five hours on the course every day. Crazy! But he’d never been there before and wanted to check out the scenery.” Jornet confirms his no-taper approach: “Such beautiful mountains! I went out, met people, ran the summits, the rivers. It’s a shame if you just go there to race.”

Jornet remains cagey when asked about the details of his Everest FKT attempt. He wouldn’t elaborate on his gear or fueling strategy, but he did divulge one tantalizing detail. To make his bid more “logical,” as he put it, Jornet plans to start much lower than 17,600-foot Base Camp, where previous record seekers have launched. Instead, he’ll begin in one of the villages below (he won’t say which one), adding another 14,000 feet and a marathon’s worth of mileage to his ascent.

“Whoa!” says Marshall Ulrich upon hearing this plan—which is saying a lot. Ulrich, 63, is O.G. FKT, a grandmaster of both mountaineering and ultrarunning, with a résumé even more daring than Jornet’s. (Doubt it? Find someone else who has run all 450 miles around the circumference of Death Valley without support, reached all Seven Summits on his first attempt, and summited Everest and run the 146-mile Badwater in the same summer.) Marshall was a seasoned mountaineer when he first climbed Everest, and it still took him five weeks. “Most people take days to hike in to Base Camp to acclimatize, and it damn near kills them,” Marshall says. “But he’s running up? Wow.”

From a risk-management standpoint, it’s tricky to decide whether Jornet should be cheered on or waved off. He’s the Rocketeer, always aiming higher and never sure if his crazy invention will bring him back from the clouds or explode in midair. If he succeeds on Everest, you can count on a generation of ultrarunners suddenly honing their ski-mountaineering skills, pulling on their skimpy base layers, and charging into the Death Zone seeking similar records on the world’s highest peaks. When asked if this kind of daredevilry could leave a lot of people seriously FKT, Ulrich doesn’t hesitate.

“I think it’s fantastic,” he says. “This guy doesn’t flinch at shit. He’s super smart and has an unbelievable amount of experience for his age. He’s reserved, not cocky. I suppose he has an unbridled adventure voice speaking to him all the time.”

Ulrich’s prediction: “He’s going to kill it.”

Christopher McDougall (@mcdougallchris) is the author of the bestseller Born to Run. His new book, Natural Born Heroes, will be published in April.

Faster, Higher, Crazier

Kilian Jornet isn’t the only one setting FKTs. He’s just leading the pack.

- Grand Canyon (rim-to-rim): Rob Krar: 2h, 51m, 28s; May 5, 2012

- Matterhorn (round-trip): Kilian Jornet: 2h, 52m, 2s; August 21, 2013

- Grand Teton: Andy Anderson: 2h, 53m, 50s; August 22, 2012

- Kilimanjaro (ascent): Jornet: 5h, 23m, 50s; September 28, 2010

- Teton Grand Traverse: Rolando Garibotti: 6h, 49m; August 26, 2000

- Denali (round-trip): Jornet: 11h, 48m; June 7, 2014

- Long Trail: Jonathan Basham: 4d, 12h, 46m; September 7-11, 2009

- Appalachian Trail (supported): Jennifer Pharr Davis: 46d, 11h, 20m; June 15-July 31, 2011

- Appalachian Trail (unsupported): Matt Kirk: 58d, 9h, 38m; June 10-August 7, 2013