-

The stamped handle of a jar from the kingdom of Judah in the first millennium BCE. These stamps are associated with particular monarchs and political regimes, all of which are associated with specific dates in the historical record.Oded Lipschits

-

You can see the jar handles jutting out of the sides of the jar, with small stamps on them. By analyzing the alignment and density of metals in the ceramics, geoscientists can determine the orientation and intensity of the geomagnetic field at the time of firing.Oded Lipschits

-

Another jar handle. The concentric circles are associated with a monarchy that ruled in the 8th century.Oded Lipschits

Earth's geomagnetic field wraps the planet in a protective layer of energy, shielding us from solar winds and high-energy particles from space. But it's also poorly understood, subject to weird reversals, polar wandering, and rapidly changing intensities. Now a chance discovery from an archaeological dig near Jerusalem has given scientists a glimpse of how intense the magnetic field can get—and the news isn't good for a world that depends on electrical grids and high-tech devices.

In a recent paper for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an interdisciplinary group of archaeologists and geoscientists reported their discovery. They wanted to analyze how the planet's geomagnetic field changes during relatively short periods, and they turned to archaeology for a simple reason. Ancient peoples worked a lot with ceramics, which means heating clay to the point where the iron oxide particles in the dirt can float freely, aligning themselves with the Earth's current magnetic field.

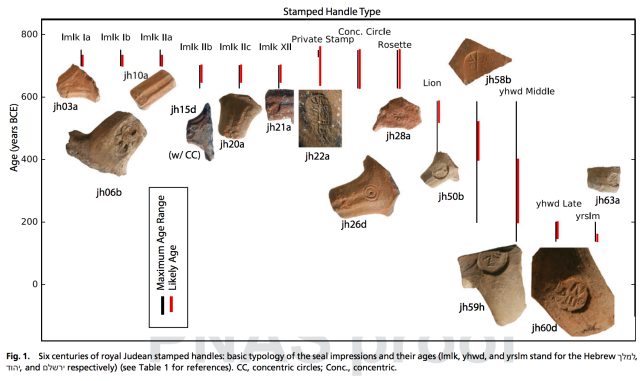

A handful of pottery shards in the ruins of Judah gave them the perfect guide to the history of the Earth's magnetic field. During the 1st millennium BCE, the kingdom of Judah was a bustling urban civilization, full of markets, bureaucrats, and scholars. They used an ancient lunar calendar system, and chroniclers noted the years of each new political regime as well as other significant social changes. At Tel Socoh, in Judah, there was a small industry devoted to the production of storage jars, and the artisans there carefully stamped the ruling monarch's symbols into each jar's handle. When archaeologists compare historical records with these symbols, it's relatively straightforward to get an exact date for a jar's manufacture. Luckily for geoscientists in the 21st century, jar handles tend to survive longer than other bits of pottery.

By analyzing the orientations of the metals in a set of these jar handles with dates from 750 to 150 BCE, the scientists were able to see traces of the geomagnetic field's behavior. What they found was startling. Sometime late in the 8th century BCE, there was a rapid fluctuation in the field's intensity over a period of about 30 years—first the intensity increased to over 20 percent of baseline, then plunged to 27 percent under baseline. Though the overall trend at that time was a gradual decline in the fields' intensity similar to what we see today, this spike was basically off the charts.

Writing in The New Yorker, Lawrence University geologist Marcia Bjornerud points out that this geomagnetic spike is far bigger than anything geoscientists had believed possible. "Both the height and the sharpness of the spike they recount push up against the limits of what some geophysicists think Earth’s outer core is capable of doing," she explains. "If the eighth-century-BC geomagnetic jeté is real, models for the generation of the magnetic field need significant revision."

The researchers note that this geomagnetic spike is similar to another that occurred in the 10th century BCE. Data from the 10th century spike and this 8th century one indicate that such events were probably localized, not global. That said, they write that "the exact geographic expanse of this phenomenon has yet to be investigated, and the fact that these are very short-lived features that can be easily missed suggests that there is much more to discover." They compare the scope of these spikes to the South Atlantic Anomaly, a region where the planet's Van Allen radiation belt dips down near the surface of the planet, trapping radioactive particles and causing problems for satellites cruising nearby.

Ancient peoples like those in Judah would not have been troubled by a localized geomagnetic field spike, but people in the same region today would call it a disaster. A fluctuation of such intensity could leave the planet far less protected from solar storms that overload electrical grids, destroying transformers and causing widespread blackouts. We often think of the post-industrial age as one where humans control nature. But in some ways, advanced technology has made humanity more vulnerable to the vicissitudes of our planet than our ancestors were.

PNAS, 2017. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1615797114

Listing image by Oded Lipschits

reader comments

99