In the last decade, the painters Ali Banisadr, Dexter Dalwood, Catherine Howe, Pat Steir, Philip Taaffe, and Suling Wang, along with one exceptional digital animator from London named simply Quayola, have produced remarkably strong painting as a result ot their immersions in the history of painting and other cultural forms. Whether the artist is painting a still life (Catherine Howe), a battle scene (Ali Banisadr), a landscape (Suling Wang), a hybrid of popular and art history (Dexter Dalwood), or digitally programming chance algorithms in the production of video paintings (Quayola), each of these painters is redefining the meaning of History Painting with a specific ideological intent. As for those painters who have used art history as a departure for their work for decades, (Pat Steir and Philip Taaffe), they can be seen producing some of their most spectacular work today as derived from the remnants of art and cultural history. Whether or not the new emphasis on art history originated as a consciously-deployed Conceptualist-styled defense against the proscription of painting pronounced by artists and critics of the 1970s and 1980s is a subject of debate. But either way, the strategy of premising painting in art history seems to have proven successful in anchoring the painterly productions of at least the seven artists featured here.

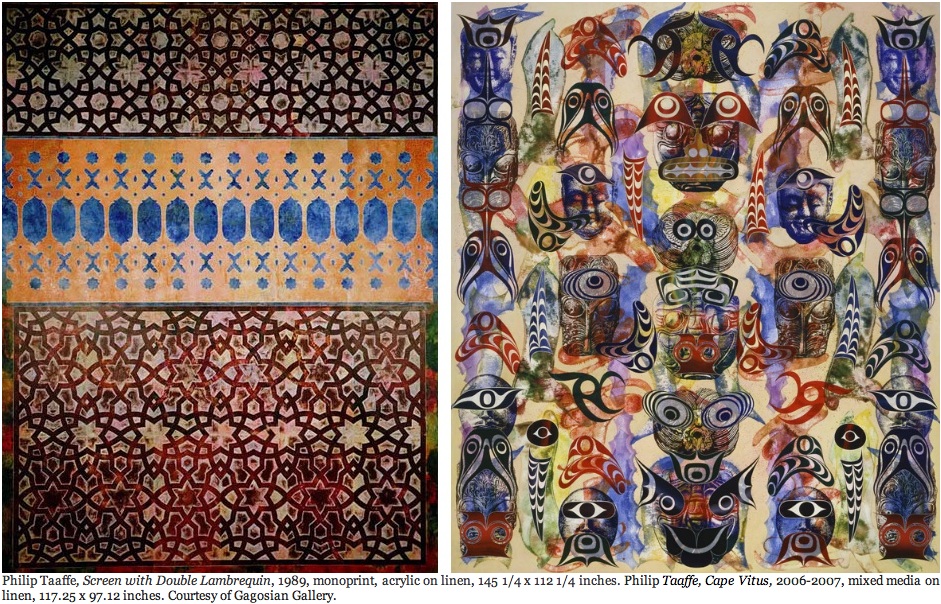

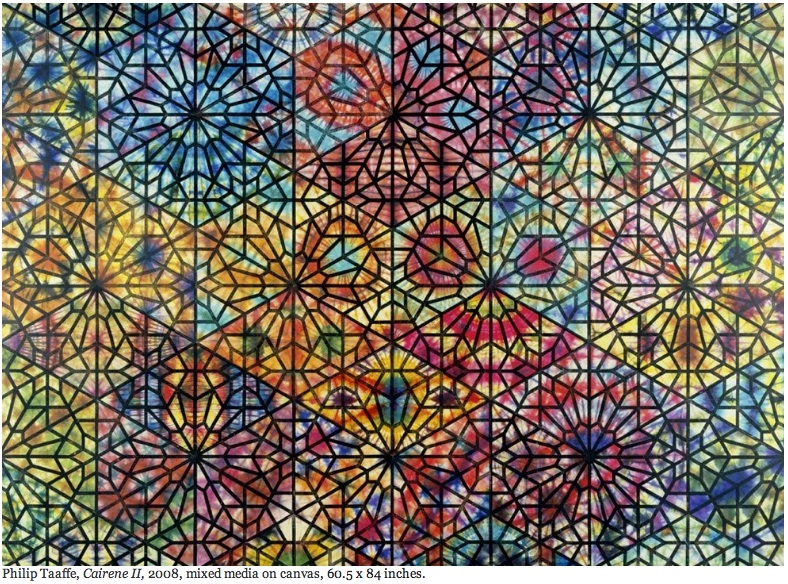

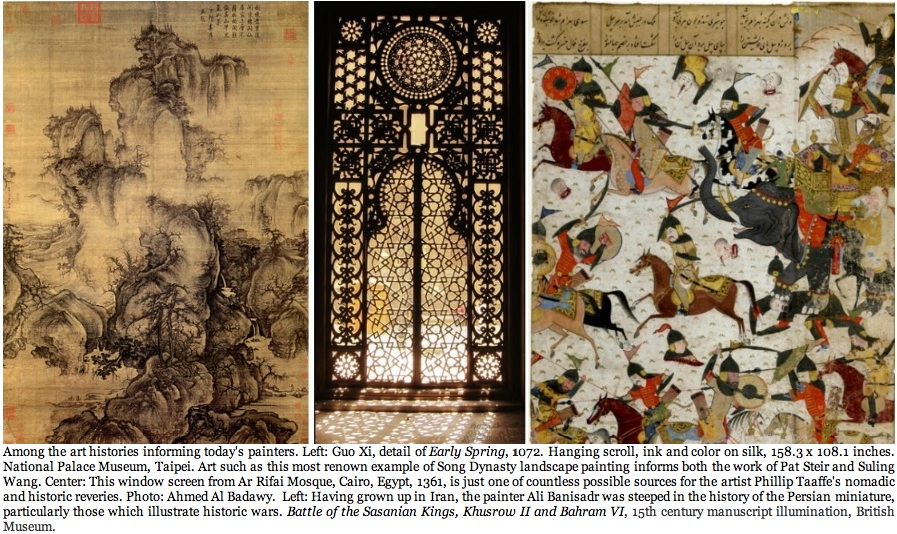

Pat Steir and Philipp Taaffe are two artists who stand out for not only enduring the decades of painting's neglect, but for also advancing their own brands of painting throughout the 1980s and 1990s by citing cultural histories as the central contextualization and function of their work. In the late 1980s, Taaffe initially achieved recognition for his superficial identification with Neo-Geo painting, which ironically appropriated formalist art to advance social theories of power and dissent. Although Taffee scavenged for richly endowed visual motifs among the architecture and ornament of the Mediterranean, North African and Asian cultures, it was his initial interest in grafting such motifs onto iconic forms and structures identifiable with the heroic modernist painters Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Beverly Pepper and Victor Vasarely that gave him credibility as one of the new ironic post-conceptualists. It also helped that at a time when Western intellectuals were being influenced by the new global, post-colonial cultural studies that Taaffe sought out and assimilated non-Western, pre-colonial motifs into his paintings and prints.

As Taaffe's work gradually assumed the aura of the new cultural nomadism being advanced by critics like myself in the late 1980s and early 1990s, he showed more confidence in directing attention specifically to the authentic Islamic art and architectural histories of Cairo, Fez, Istanbul, Isfahan, and other historical Islamic centers. By the mid-1990s, Taaffe clearly had become a nomadic ideologist collecting and conjoing historical motifs derived from the traditional cultures of India, China, Japan, and the various nations of Africa and the Mediterranean. Taaffe by all appearances had become so enamored with making the nomadic assimilation of world art-historical motifs the basis of his prints and mixed media paintings, that he easily became the most capaciously nomadic artist of the last two decades.

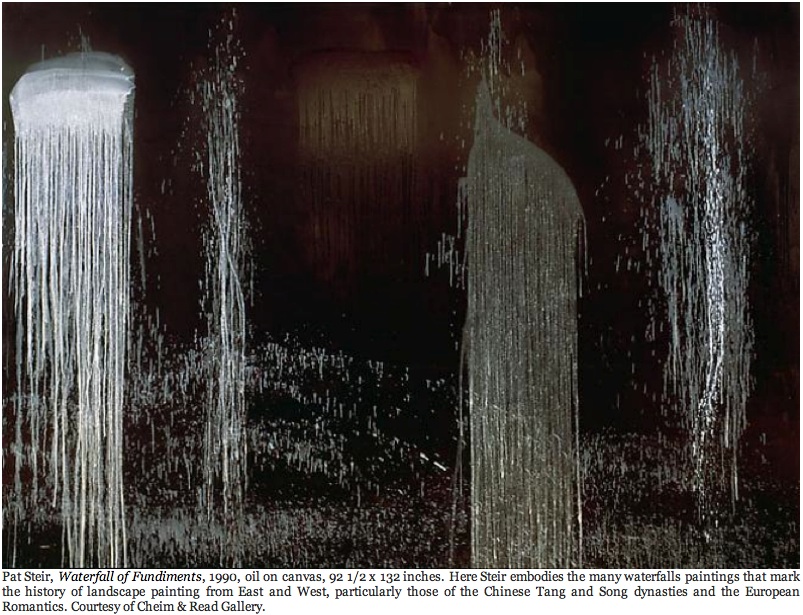

Throughout the years that Conceptual Art dominated the art press, Pat Steir remained committed to authentic, non-ironic painting, though even her waterfalls paintings, in their attachment to Abstract Expressionism, doubled as ironic citations of Chinese art history. Steir's attachment to painting may be credited as the reason why her formidable accomplishments were not always commended with the critical approbation they deserved. But by the mid-1990s, critics became more acutely attuned to Steir's excursions into the history of Chinese, Japanese and Tibetan painting that informed thirty years of her work. The majority of this period was devoted to a series of waterfalls and mist paintings born from Steir's interest in the painted scrolls of the Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1269 CE) dynasties. By thinning her paint to the consistency of a wash, keeping it restrained, flat, and ungraduated, as if it were an ink, Steir evoked the pictorial surfaces of Tang and Song landscapes, though as if seen up close through a zoom lens tightly framing only the representation of waterfalls. Steir also explored the full spectrum of vibrant color in her Lhamo series, in which she had turned to centuries-old Tibetan Tonka paintings for chromatic cues.

Although Steir's compositions were composed from no more that thinly-hued washes allowed to cascade down a vertical canvas, the rhythmic intervals between each downpour came to echo the mountain contours found in Tang and Song landscape paintings. In this sense, Steir mimics a natural history in which the contours of mountains come to support waterfalls and determine the water's course, even as the water perpetually rasps out the contours and furrows of the mountain.

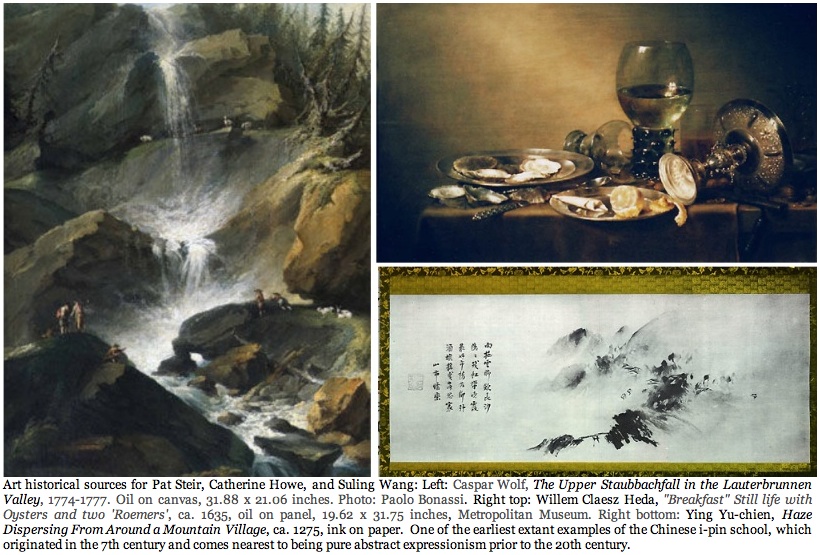

Even Steir's decision to close in on the waterfalls rather than articulate the contours of rocks and gullies is informed by art history. The flat, frontal emphasis she favors is derived from Romantic painting made in the last decades of the eighteenth century, from whence we can coherently compare certain of Steir's paintings to the Swiss artist Caspar Wolf, when he painted mountains and waterfalls frontally and parallel to the picture plane while radically depicting a spatial ambiguity that, in the words of the art historian Jean Clay, "makes the foreground seem unstable and floating." Some watercolor paintings of waterfalls by J.M.W. Turner also appear to inform Steir's work of the 1990s and 2000s, particularly those that bring the wall of the mountain and waterfalls so close to the frontal plane of the canvas that they reduce the illusionistic three-dimensional recession to almost nothing.

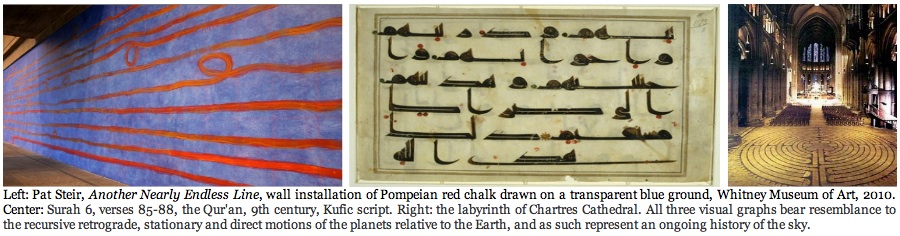

In 2010, Steir has turned to the historical motif of the nearly endless line. It's a motif that harkens back to mystery cults of Crete in bearing resemblance to the thread that Theseus unwinds as he circumnavigates the labyrinth in search of the Minotaur. Considering that the labyrinth was analogized with eternity among the stars, and commemorated with the constellations (Taurus, Ariadne's Crown), the nearly endless line becomes a metaphor for the soul, psyche, or spirit believed to fill each living thing and tying them together in the nearly endless continuum that is the sky.

Steir's 2010 Whitney Museum installation, Another Nearly Endless Line, seems to derive from a more empirical history, the same history that is the source for the myth informing the design of the Cretan labyrinth. It is also a history of the sky, though this time a history long documented by astronomers and astrologers. I'm referring to the observed retrograde, stationary, and redirect motions of the planets relative to the Earth's orbit. The seemingly erratic motion of Mercury is thought the most likely astronomical history informing the myth of the Minotaur's labyrinth. Both Steir's Another Nearly Endless Line, and A Nearly Endless Line, installed at the Sue Scott Gallery in New York, certainly bear uncanny resemblance to graphs of Mercury's direct-retrograde-stationary-redirect motions in the sky -- and which from the earth appear to be labyrinthine in changing directions a total of seven to nine times per year. The ancients came to represent these back and forth passings of the Earth by Mercury as a circuit of recursive swings enclosed by a circle (the orbit of the planet around the sun), and which became a symbol for the Cretan Labyrinth of the Minotaur. Since then the symbol of labyrinthine motion has cropped up in the symbology of the world, from the circular maze set into the floor of Chartres Cathedral to the illuminated manuscripts of the Qu'ran.

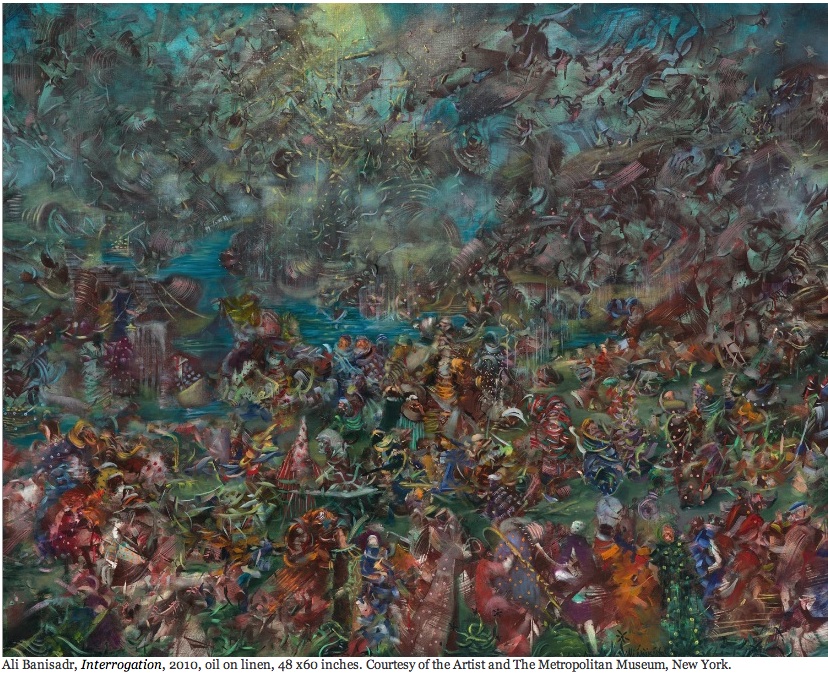

Ali Banisadr traces his interest in international history to Tehran, 1980, the year that the artist was four years old and the Iraqis invaded Iran. As bombs fell around his home, Ali retreated into hiding places from which he drew pictures of monsters. Today Banisadr sublimates his childhood trauma in a series of panoramic paintings that by all appearances consolidate a grand history of warfare with abstract citations of diverse painting histories, including Italian Futurism, Russian Constructivism, Abstract Expressionism, and the Persian, Mughal, Ottoman and Arab miniature paintings developed from the 13th century on. With such an array of cultural references, Banisadr's painted gestures can as justifiably evoke a clash of turbaned 13th-century warriors on horseback as they can recall a rendition of Hieronymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1480-1505), or a host of nude saints by El Greco raining from the skies in a style comparable to that of Adolph Gottlieb or Willem de Kooning. In turning cultural and historical manifolds in on themselves, Banisadr registers brightly among the more sophisticated of the new culturally-nomadic painters.

Remarkably, despite their pictorial obfuscation (perhaps analogous to reconstructions of receding memory), the compositions are immediately recognizable as human crowds, and hence the sites of sociology and history. Considering that History Painting as a genre is near synonymous with the battle painting for many viewers, it seems fitting that Banisadr's most spectacular compositions are comprised of pictorial arrangements of figures that appear to charge through and leap across great expanses of geography, time, and culture. For many viewers, the blur of the paint strokes evoke compositional comparisons with cinematic portrayals of battles, migrations, and assembled crowds--as if the filmsLawrence of Arabia, Blackhawk Down, or Gandhi were played on fast forward (or in reverse!). It's the pitched angularities of the painted "crowds" (which really are no more than adeptly applied squiggles in paint) that effect the illusion of fighting, or when more rounded and evenly spaced, the coordination of balletic figures across expansive sets. Despite that many of the compositions evoke a charge into chaos, Banisadr's abstractions manifest a balanced and perspectival order presiding throughout massive human assemblies -- what are really no more than fields of recursive lines, shadings, and intervals.

Catherine Howe has produced her generation's most sumptuously inviting yet socially-decadent conflations made in the name of painterly reflection. For the last twenty years she has painted some variation of expressionist figuration, usually with readily-apparent allusions to art history. Her most recent work, shown last spring at the Thomas Von Lintel Gallery in New York, applies the notion of expressionist entropy to her own singular rephrasing of the epoch of still life paintings issued in 16th- and 17th-century Netherlands and Flanders, the most famous being categorized under the rubrics of vanitas and pronk painting.

Howe especially lingers over exquisite portrayals of beautiful objects, both man-made and organic, envisioned by the Dutch and Flemish masters to convey the transience of life on earth. In this respect Howe disregards the severe and blunt vanitas paintings of skulls and decay in favor of over-ripe and peeled fruit, liquors languishing in food- and lipstick-smudged glassware, and the blooms of flowers showing the first signs of their demise to come. But above such significations, Howe esteems "the moment" that will endure forever in art, and like the Dutch vanitas painters, instead of choosing to memorialize the peak of beauty, she captures the lingering evidence of the party that has just ended, yet is still felt by its revelers in the flush of night-long intoxications. The pronk still lifes are especially valued by Howe for their extravagantly-rendered, shimmering-to-the-point-of-ostentatious details, thereby inviting the lurid sensibilities of the contemporary expressionist painter to exploit their reinterpretation in an orgy of sensual overindulgence.

Howe's overindulgence in sensuality, however, is intended to seduce us into lingering long over the thought that both expressionism and vanitas-pronk paintings place emphasis on the immediacy of observed nature. She regards the visual hedonism unleashed in such paintings to be the sustaining grasp on what otherwise would be an ultimately uncontrollable and altogether vain pursuit of pleasure. In her re-enactment of the Dutch and Flemish sense of the visceral, she intuits that painting expressionistically allows her to visually sustain the feeling of being vitally alive, even if for only a moment. "Despite that I'm slipping away," she wrote to me in an email, "I have this acutely felt moment." Naturally, such a desire to prolong the ecstasy of painting would draw Howe to art history, considering that history prolongs our sense of the moment "slipping away from us." Of course, it can be claimed by some theories of time that "the moment" is never "really" slipping away as much as it is transforming, perpetually, as an eternal "moment" of the present.

Before Howe revealed to me that she perceives an affinity exists between expressionism and vanitas painting that can be found in the valuation of the sustained moment, I never associated the two genres as sharing a credo for painting of the moment. Their styles are nothing but acutely different on the surface. Expressionism shows none of the pain-staking patience and technical skill required of the vanitas still life painter. The vanitas paintings give little room for the neurological idiosyncrasies of the individual painter to spread out. It is this foresight that graces Howe with an empathy for two styles that are best coincided, if not reconciled, by bringing history to expressionism, the mode of painting-in-the-present least accommodating to historicism.

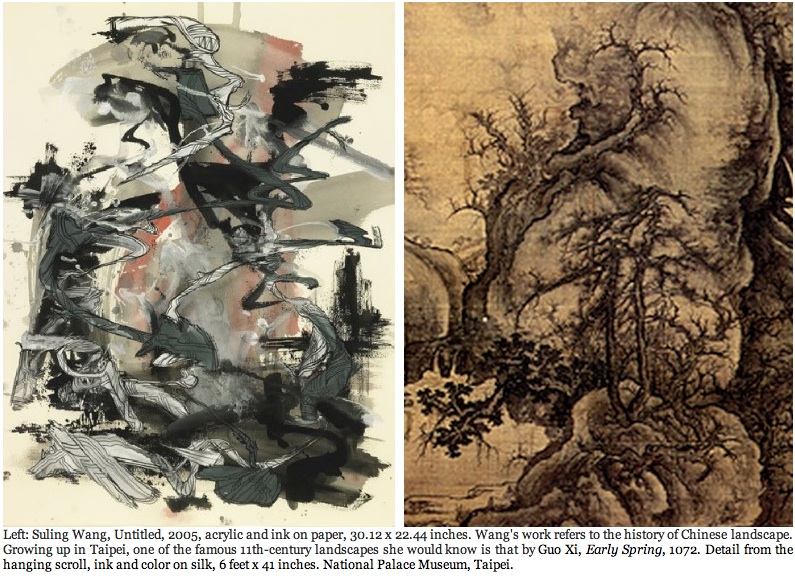

Like Pat Steir, but with a deep sense of ancestral heritage, Suling Wang reaches back to the Chinese Song, Tang, and later dynasty painters who thought of painting as thought-in-action. Born in Taiwan, it is only natural that Wang perpetuates a principle memorialized by the 12th-century commentator, Chang Yen-yuan, when he writes: "Painting perfects culture, governs human relations and explores the mystery of the universe. Like the rotation of the seasons, it regulates the rhythm of nature and man." In the shadow of such an overarching aesthetic ideology, it is little wonder that Wang would be interested in reprising principles and styles of Chinese art.

Westerners generally don't realize that Wang's abstract paintings not only reprise abstract expressionism. She is also citing the contributions of such ancient Chinese artists as those known as the i-p'in or "untrammelled class" of Tang Dynasty painters (618-906 CE). Some centuries later, the haboku or "flung- and splatter-ink" painters of Japan, who influenced both the art of Taoism and Zen Buddhism, would also take up the innovations of these rebels from across the sea. In the West, Abstract Expressionism is generally proclaimed the great American contribution to late modernism, just as in Japan, the haboku artists of Japan received much recognition for their own splattered ink-scapes. Strictly speaking, however, both schools resemble the much earlier innovations of the i-p'in painters and their followers. The reason that this history isn't better known is because the i-p'in painters of China were viewed as radicals of their day, and thus as potentially devastating to Chinese orthodoxy.

Other of Wang's paintings evoke the Tang Dynasty innovation of p'o-mo, the broad movement of a brush heavily diluted with thin ink and the pronounced splotches it produces across its material support, often creating shapes without clearly recognizable contours. Wang's gestural paintings in this respect aren't as closely related to the existentialist marks of the abstract-expressionist as they are to the free-form splashing technique that the p'o-mo painters, whose interests in painting landscapes only took on the vaguest contours of mountains and rocks serendipitously, while betraying their very real technique as an application of a few quick brush strokes that were not so easily recognizable as mountains and rocks. Such historic paintings were achieved with very wet applications of ink onto silk spread out over the floor.

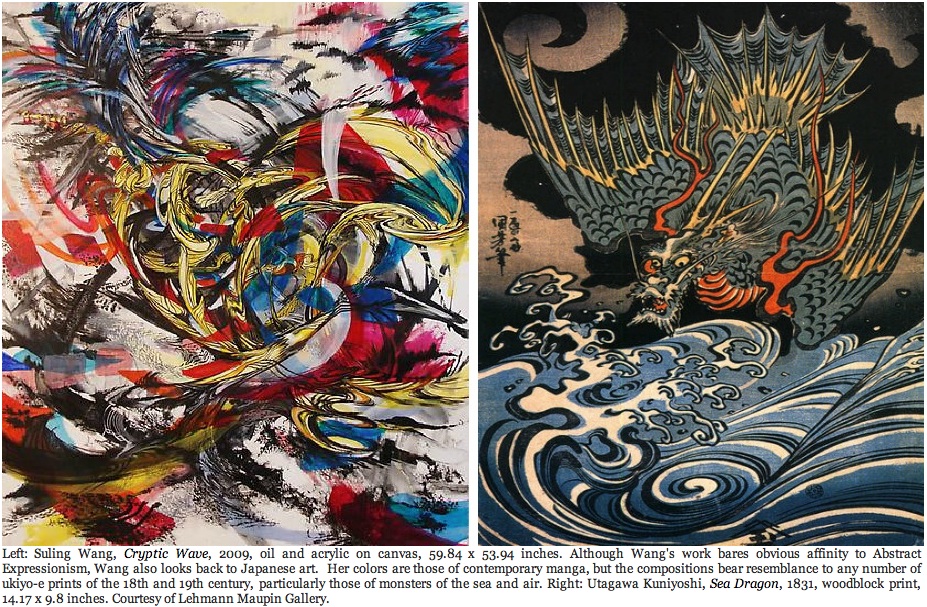

Wang has also lived extensively in London, and she cites as influences the art of Disney, Japanese manga, and the ukiyo-e prints of Japan's Edo period. In those paintings that are most difficult to identify a single or dominant art history, multiple histories may be functioning at once, producing a dynamic visual tension, but also a historical paradox, given that the principles from which these artistic movements derived were in ways antithetical. In this regard, Wang exemplifies how contradictory and oppositional principles may cancel each other out logically, they can be made to cohere and coincide with a unity when applied judiciously in a visual composition.

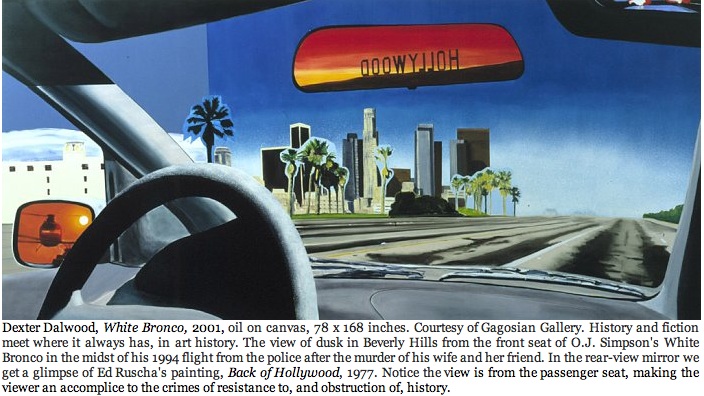

Dexter Dalwood is the most diligently reflexive of the history painters, having made a career of questioning by example of his art historical pictures both the construct of history and our public participation in the perpetuation of historical narratives that very often are supported by only the most circumstantial evidence and cultural prejudice. While the painted techniques and styles that Dalwood settles on for each painting changes according to the historical narrative being depicted or embodied, the greater body of his work might be thought of as orbiting around two distinct conceptual nuclei -- each with its own gravity of narrative. The first conceptual orbit is made around the history known to a wide, sometimes global, audience from either the news or from written historical accounts. The second orbit is made around a lesser-known art-historical reference. When the two orbits coincide, Dalwood has made a pun, though usually one only the art cognoscenti will get--though often it takes some explanation. Whatever the success of the pun, Dalwood's conflation of popular and art history reinforce whatever doubts we hold about how a consensus on history is formed and handed down to us largely on faith.

White Bronco, 2001, is the kind of painting that we can easily enjoy for its punning use of art history, however cynically the pun reflects not just the skepticism surrounding the notion that history is a product of expert consensus based on evidence. It also reflect the skepticism that follows the notion of verifiable truth, particularly when such truth is claimed for a reconstruction of events in time entirely removed from our experience.

Dalwood has painted the view from the passenger seat of O. J. Simpson's infamous SUV, the same vehicle Simpson made his flight from the police for the alleged murder of his wife, Nicole Brown Simpson and her fiend Ronald Goldman. Most of us know Simpson's White Bronco from having seen it on live television or video footage, but Dalwood here presents us the privileged view from the passenger seat at the moment that Simpson finally stops to be apprehended after twenty LAPD vehicles and police and news helicopters were furiously in pursuit of the Bronco on the freeway. Through the windshield we see the oncoming dusk ahead, but it is from the rear-view mirrors that we see, to the left, the News Helicopter from which the famous footage has been filmed, and above the windshield, sight of the sun setting not on the Hollywood sign as we all experience it in on a visit to Beverly Hills, but as it has been painted by Ed Ruscha in his iconic 1977 painting, Back of Hollywood.

In the real flight, the passenger seat is empty, but by putting the viewer in the seat of the white Bronco, Dalwood is making the viewer an accomplice to the crime of resistance and obstruction, if not the murder itself, depending on what the viewer believes about Simpson's guilt. The point is, in all history portrayed in art, the viewer is made a participant in the act of conflating history and fiction by the simple act of complying with the re-enactment.

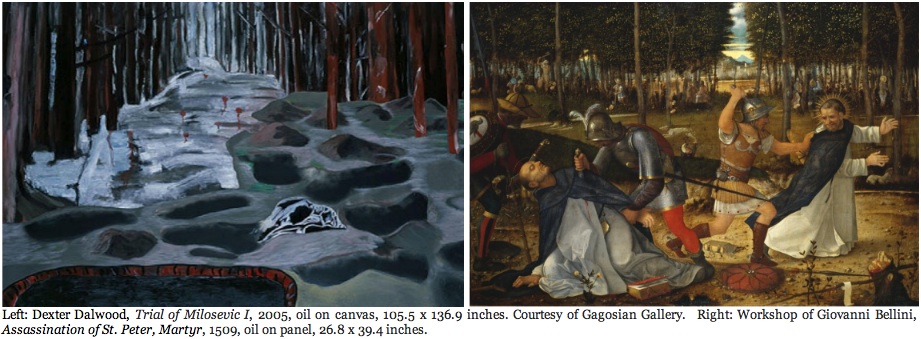

Dalwood's Trial of Milosevic I, has a more forceful, if subtle, gravity pulling us in. It too is arrived at by conjoining political history and art history. At the time that the former President of Serbia and architect of ethic cleansing, Slobodan Milošević, was defending himself against charges of war crimes at the five-year trial in the Hague, Dalwood was at work on a series of paintings based on Giovanni Bellini's painting, Assassination of St. Peter Martyr, that hangs in the Courtauld Institute Galleries in London. On the Courtauld's Art and Architecture site, in an interview with John-Paul Stonard, Dalwood attests to having been drawn to the Bellini painting because it depicts "a European atrocity, an execution in a wood -- which seemed to be somehow universal. Executions continue to occur in woods ... mass graves found in woods." In another artistic era, a painter treating the subject of the tens of thousands of people slaughtered and raped in the rural areas surrounding Kosovo, Croatia and Bosnia would approach the subject directly and with moral indignation. But the lingering predilection for irony and art historical citation and analogy prompted Dalwood to instead paint his own commentary on the massacres. To begin, Dalwood enters history through a portal opened in the woods by Bellini five centuries earlier. It's a contrast in styles and beliefs that attests to how fashions in art and thought have complicated the representation of history in painting significantly.

We might ask whether it is indicative of the desired restraint of some of the new historical painters in vogue that Dalwood chose to paint the newly discovered graves in the woods of Kosovo (Or Croatia or Bosnia), or that it is his interest in drawing analogies between historic and popular art forms, in this case the vogue for CSI-styled TV that compelled him to paint the wood as a crime scene with many of the hidden graves opened and others further in the background tagged with red markers, not unlike those seen on CSI and countless TV imitations. The point is that, for those of us divorced from direct involvement in the historical events being depicted and contextualized by the artist, the reality of the history portrayed is no more certain than a fictional narrative, the product of an author, director, editor, et. al. To underscore the human condition of our inevitable and rightful doubts about history even further, Dalwood has chosen world-renown cases in which many key questions remain unanswered. Both the O. J. Simpson trial and the Hague trial of Miloševic ended without sufficient proof of guilt concluded, and thereby without convictions for their infamous defendants, despite that the overwhelming majority of public opinion on both men holds them guilty.

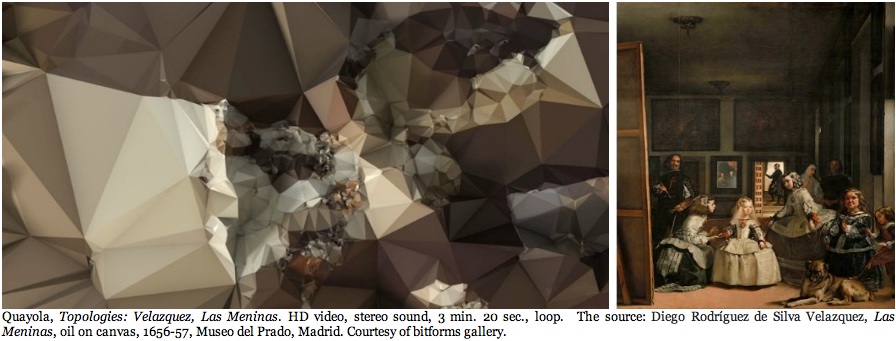

By including the London-based digital artist Quayola in a survey of painting, I must first explain why I consider his work not just video, but also painting. After all, the work is definitively occupying a picture plane experienced either on a computer, an HD flatscreen, or projected onto a wall or screen. Still, many of us fous not on the pictorial function, but on the medium we know as video. But such conventionalism neglects that significant artists of the last century argued that the use of light as a medium is more truly two-dimensional than the application of paint on a surface -- what many rigorous artists claimed is actually sculpture, given that both paint and its support are three-dimensional. We know from the work of Dan Flavin, Marian Zazeela, and James Turell that light can be presented as a formal component of both painting and sculpture as defined by the intent of the work as either conveying two or three dimensional information. In Quayola's case, the use of software to establish algorithms that convert and project color and light as a picture, is by definition a kind of dematerialized painting, as the Dada, Surrealist and Fluxus artists pointed out when they introduced random and pre-programmed operations into the artistic process. Then, too, animation has always been a kind of kinetic painting and needs little justification.

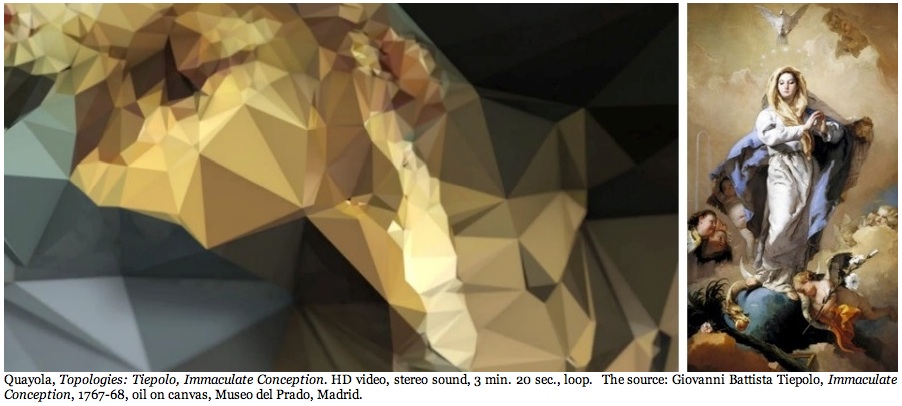

Having grown up in Rome, Quayola has a rich sense of what history means in terms of the layering of successive periods of time, both conceptually and in the archeology of objects. Anyone who has visited the city knows that Rome is also a city of unparalleled convergences, for our purposes the convergences of multiple styles of art experience. Within a short walk, often within a single neighborhood, the visitor to Rome is apt to experience the pre-classical, classical, romanesque, gothic, renaissance, mannerist, baroque, rococo, neoclassical, romantic, and modernist within moments of one another. It should come as no surprise then, that Quayola, when commissioned by the British Film Institute and onedotzero, should have conceived a work such as Topologies, in which he by means of algorithmic manipulation, transforms images of Las Meninas (1656) by Velázquez and The Immaculate Conception (1767) by Tiepolo into abstract animations that effect the illusionistic folding and unfolding of the two paintings. Although the loops of both unfoldings are no more than 3:20 minutes long, we infer from the experience that the possible variations of folds is unlimited.

Quayola has elegantly crafted a new model of painting, one we've been anticipating since the beginning of modern painting and cinema. In essence, Quayola inherits the mantle of Cezanne, Picasso, Braque and Leger in extending the cubist predilection for showing multiple, if fractured, perspectives in a single image simultaneously. His extension, of course, is made in time, but also in sound. Specifically the soundtrack that plays in the space. As somewhat of a media purist, at least in early innovations, I prefer that the work was silent. But as it turns out, the soundtrack is structurally instrumental in generating the work's visual permutations. To convey why sound and math are so important to Quayola's structural process, I'll quote the bitforms gallery press release that accompanied the work's installation in May-June of this year. "In each panel," the release states, "hundreds of thousands of polygons and points comprise a wire frame core that mathematically contorts and regenerates, driven by a soundscape that visually is determined." After viewing Topologies, I went to MoMA to look at the art of Cezanne, the Cubists, and the Futurists, and imagined the same temporal process of permutations applied to them. The continuity, though making Quayola seem conservative in extending a movement already over a century old, is no less a significant paraphrasing of the logic of Cezanne's painted canvases. It's a logic that Cezanne implies every time he painted a stroke on a canvas in a manner that conveys he has entered a different point in time in the picture plane each time he applies a brush stroke, just as each experience of an object in the world is a different experience of that object no matter how similar the object by appearance remains. Quayola also reportedly cites Kandinsky's observation that "Time is an inseparable quality of my primary experience with an object."

All of this confirms that Quayola has his feet planted firmly in modernist ideology, which translates as modernist history. The challenge he has yet to confront is making such ideology pertinent to the present day activities of artists. So long as the art world perpetuates the myth of the avant-garde as a prerequisite for its accolades, renown, and assimilation into artistic canons, Quayola will have to show us how his algorythms unfold sight of the future.

No doubt our reluctance to leave behind history to instead paint pictures or abstractions free from historical reference indicates that we are still in some mid-stream of our re-evaluation of painting begun in the 1960s. This was, after all, the period we called postmodern, with painting having seemingly come to its logical finality and exhaustion at the end of the modern era. Now the preoccupation with looking back at the history of painting is what follows.

If we instead follow the lead of the art critic Thomas McEvilley, we might come to understand that this is just one more cyclical development. In fact, McEvilley sees it as one of many past modernisms followed by postmodernisms -- or what, always in retrospect, historians have called classical periods followed by post-classical periods. McEvilley cites the ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Greeks, Romans, Indians, and Renaissance Italians as all having produced modernist and postmodernist epochs. And we may, through his example, easily imagine the modernisms of China, Japan, Persia, Turkey, Nigeria, Peru, and Mexico among others doing so. Modernism was our classical period; postmodernism and whatever we wish to call our present global, nomadic and relativistic development, is our post-classical phase. And though we may for the moment be preoccupied with histories of painting, history itself shows us that the post-classical periods similarly predisposed to looking back rather than looking forward is what eventually leads to a new forward-looking classicism. And one that includes a rich diversity of painting.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.