Tasmania’s loggers and forest activists still talk bitterly about “the bad old days”.

“A logger turns up to work in the morning and finds that someone’s been on site and defecated in his helmet, or urinated in the billy, or put excreta up under the handles of his machines,” is how Terry Edwards, the head of Tasmania’s logging industry association, remembers it.

Death threats to his home became unremarkable. “I personally don’t get too worried about it,” Edwards says. “But when I have a young family and they’re picking up the phone … it’s getting to the point where it goes too far.”

Sally Meredith joined a blockade to stop a logging road in 1990. She remembers being alone at the barricade with two other women when a convoy of timber workers approached. Drunk and furious, they pelted the women with rotten eggs. She takes a deep breath. “Somehow we have to stand back from the emotional intensity of it because I think it brings on sickness,” she says.

In 2008, loggers were caught on video swarming a protester’s car, attacking it with sledgehammers. They demanded the 22-year-old driver get out, and when he didn’t, he was dragged from the car and beaten.

And so it went for more than three decades in Tasmania, a tree-by-tree battle between activists and timber workers that tore apart the Apple Isle.

And then in 2010, Greg L’Estrange, the boss of the state’s biggest logger, Gunns, famously declared the industry had been “out-thought and out-played”. The market had turned in favour of cheaper plantation fibre from Asia and South America. Years of savvy campaigning had seen Tasmania’s products branded “conflict wood”. Gunns was getting out of native forests.

Adversaries in the timber industry and environment movement suddenly found themselves sitting around a table trying to secure an improbable peace. Within three years, shortly before the Tasmanian Forestry Agreement (TFA) was signed, then-deputy premier Bryan Green made an announcement: “The war is over.”

But what took three years to negotiate was undone in three hours on 2 September this year, when the newly elected Liberal government of Will Hodgman achieved its first major legislative accomplishment: tearing up the “job-destroying” TFA.

His resources minister, Paul Harriss, told parliament that “Tasmania’s forestry industry, and the use of our forest assets for economic gain, is not something of which we should be ashamed”.

Echoing the calls of the prime minister, Tony Abbott, for a “renaissance of forestry in Tasmania”, Hodgman’s government removed 400,000 hectares of native forest from reserves, designating it “future potential production forest land” – available to be logged in six years’ time.

A further 1.1m hectares of forest has been opened to the “speciality” wood sector, who harvest what might be considered the state’s rarer boutique timbers, among them myrtle, sassafras and huon pine, reputedly the oldest tree in Australia.

In parallel, the Hodgman government is pushing anti-protest laws aimed squarely at the environment movement. Under the proposed legislation, protests that disrupt business operations or block access to worksites would be punishable by fines of up to $100,000. Repeat offenders could face three months in jail.

Last week, the UN special rapporteur on freedom of opinion, David Kaye, warned the laws would “chill expression and people speaking out”. His colleague Michel Forst, the UN rapporteur for human rights defenders, described the bill as “shocking”.

Sally Meredith’s hair now is whiter than in the photographs on her kitchen table. She’s pictured mostly in thick eucalypt forests, standing with a gang of other protesters, their faces smiling or set in fierce determination. “We were young and passionate then,” she says.

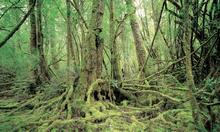

She lives deep in the Wielangta forest, about an hour east of Hobart, in a house that her partner, Mark Agnew, built himself from recycled timber. The thickets of mighty eucalyptus trees that surround the property roil with the sounds of wildlife and a piercing, heavy wind. Wombat burrows pockmark the back garden and pademelons routinely bound up to the window. The edenic vibe is broken only by a flimsy badminton net strung in the backyard.

This article includes content hosted on tasmania360.com. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as the provider may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

Their move to Wielangta in the early 1980s coincided with advances in logging technology, among them cable logging, whereby a great mechanical arm was strung high above a patch of forest and winched felled trees out from inhospitable landscape. It allowed previously unreachable parts of the forest to now be shorn clear. “Suddenly whole hillsides were gone in a matter of months,” Meredith says.

Blue ribbons took on a horrible significance. They would be tied to trees to mark out an area that was set to be chainsawed. Ribbons began to appear all over Wielangta. In 1990, Meredith and Agnew drew up placards, recruited two others, and went to block a proposed logging road.

“And they stopped,” she says. “They stopped that road being bulldozed just above the reserve. That was the first political action.” For the next fifteen years, Agnew would look after the couple’s two daughters, while Meredith joined protests around the state. “Having lived in this exquisite place for a number of years before logging really really went into top gear, we couldn’t just stand by,” she says.

The signing of the peace agreement, which put Wielangta into reserve, was “an extraordinary moment”, she says. “To drive to and from our place and not encounter log trucks, not encounter log trucks anywhere in the state, was a sheer pleasure, really.”

In six years, the forest will again be open to logging. The protests, the blockades, the bitter conflict – “it’s all going to come back again I think”, Meredith says.

A framed axe hangs on Terry Edwards’ office wall. As chief executive of the Forest Industries Association of Tasmania, he led the industry’s peace negotiations with the unions and environmentalists. “It was surreal in a lot of ways,” he says of sitting across the table from his old enemies. “The level of mistrust on both sides was something that was quite palpable.”

Like the environmentalists, he faced additional pressure from elements on his own side, who believed any talks with the green movement were a heresy. “It’s been pure ideology at both ends of the spectrum,” he says.

Months of skirmishes and debate around the table eventually grew a grudging respect, “a sense that the people on the other side are fair dinkum and prepared to take on board your ideas and not just simply dismiss them”.

“A couple of times after we finished late at night we’d go and have a beer together. Just a couple of beers, and then go home,” Edwards says.

When Hodgman was elected in March and pledged to scrap the TFA, Edwards was initially resistant, asking the government not to act with “unnecessary speed” and to consult the peace deal’s stakeholders.

Last month he relented, backing the new forestry regime for essentially pragmatic reasons. “As a lobby group we’ve got to be able to work with the government of the day, regardless of their political persuasion,” he says.

“Now do you work with a government by saying, ‘your policy is crap’, or do you work with them and say, ‘how can we help you make your policy position work in the context of everything else going on in the bigger environment outside?’”

Bizarrely, the industry’s advocate now finds himself in the position of trying to salvage some of the conservation outcomes from the TFA. “Dialogue got us to where we were. We had then an external force, being the government, who wasn’t interested in dialogue, and just said, this is our policy position,” he said.

“I think just talking to people who agree with you becomes quite an insular conversation after a while. You’ve got to consider to economic, the social, the environmental. I always look at it as a stool. If you take one leg off a stool, it won’t stand.”

Edwards is no tree-hugger. He just knows how to read a balance sheet. What convinced the timber industry to sit down with environmentalists in 2010 was a recognition that the market for wood had fundamentally changed.

Plantations in Africa, south-east Asia and South America had come online and flooded the solid wood and woodchip markets with cheap, plentiful supply. The Australian dollar rode the mining boom to parity with the United States. Years of market-focused activism by environmental NGOs had also succeeded in muddying Tasmania’s brand, raising the spectre of boycotts and bad publicity among the industry’s biggest customers in Japan.

According to analysis by the progressive think-tank the Australia Institute, nearly 40% of Tasmanian forestry businesses disappeared in the five years to 2011, and the number of jobs in the industry nearly halved to about 3,400. When the global financial crisis sent the housing construction market around the world into a tailspin, the game was up.

Tearing up the TFA doesn’t alter the tough economic climate, Edwards says. “There are challenges … I don’t think the industry in terms of demographics will grow.” Rather he hopes to see Tasmanian forestry “consolidate”, and build a mill to process chipped wood in Australia, instead of sending it to mills overseas.

A little logo depicting a scrawled tree, the seal of the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), will also be essential to the industry’s future. Without the council’s certification of Tasmania’s forest management practices, foreign markets spooked by the bad old days could stay out of reach.

Environmentalists say it’s an application blatantly threatened by the prospect of opening 400,000 hectares of native forest to loggers.

That’s a serious concern for the company that succeeded Gunns as Tasmania’s biggest logger, Ta Ann. “Markets are beyond politics. At the end of the day, we need to listen to what they’re saying,” Evan Rolley, Ta Ann’s CEO, tells Guardian Australia. “Those markets are saying ... our preference is FSC certification,” he says.

Ta Ann has made its own deals with green groups, pledging not to harvest wood from any areas outside those agreed in the peace accord. Some of the same environmentalists who used to target Ta Ann’s sites have now visited its Japan customers three times to stump for the company’s green bonafides. The tearing up of the forestry agreement has put that cooperation at risk, Rolley says. “Frankly, we’ll need to figure out the ways that we can continue to work together.”

Tasmania’s major green groups are plotting their next steps. Phill Pullinger, forests campaign director at Environment Tasmania, one of the signatories to the peace deal, warns against any “knee-jerk responses”.

“We know that partly, what’s driving the Liberal government here is wanting to drive divisions and conflict and hatreds in the Tasmanian community. We don’t want to act in a way that buys into that, when most Tasmanians want to move on,” he says.

But the door appears closed to further negotiations. The Hodgman government has created a ministerial council to advise on the future of the state’s forestry industry. No environmentalists have been invited.

And for a harder core of forest activists, such as Jenny Webber, that’s just fine.

Webber is more likely to be found clashing with loggers and organising blockades than sitting around a negotiating table. She works closely with another activist, Miranda Gibson, who recently spent 449 days living in a 400-year old eucalypt tree in state’s Tyenna Valley.

Now a campaign manager with the Bob Brown Foundation, Webber felt her cause was betrayed when the state’s major green groups, Environment Tasmania, the Australian Conservation Foundation and the Wilderness Society, signed the peace deal.

“It completely undermined everything we were doing,” she says. “When we first got involved in the treaty, I thought we were all on the same page for a transition from native forests to plantations.”

But when the green groups compromised, allowing limited native forest logging, Webber balked. “That’s not something we are willing to move on.”

The Hodgman government’s pro-logging drive has confirmed her view that negotiations with the industry are impossible, and that only direct action can secure her aim, a complete moratorium on logging native forests.

The “hare-brained” idea of negotiating peace is now “well and truly over”, she says.

“Peace is when you’ve got a protected forest and you don’t have this foreboding feeling that someone is about to arrive with bulldozers and trash it. That’s what I see as peace. It’s not about trying to fix some conflict.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion