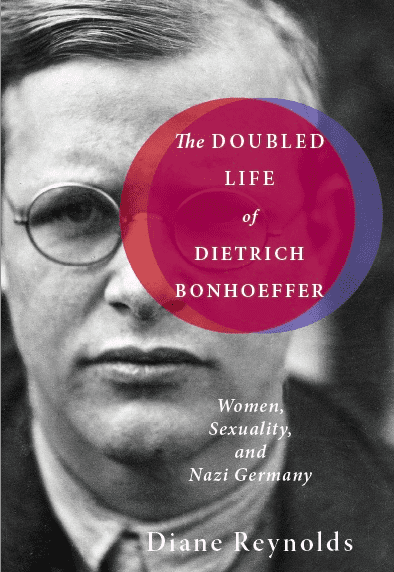

There are a number of very important biographies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, none more complete or significant than the one by Bonhoeffer’s friend, Eberhard Bethge (Dietrich Bonhoeffer: A Biography). Bethge’s biography is complete though not exhaustive (even if at times a bit exhausting) and takes serious commitment to finish. The prose is not captivating. Alongside Bethge is F. Schlingensiepen’s solid and recent biography (Dietrich Bonhoeffer). Those two describe a similar journey for Bonhoeffer (see below) while Eric Metaxas (Bonhoeffer) told a different story, a more evangelical one, which is why so many evangelicals have found Bonhoeffer in the last five years. Mark Thiessen Nation provides in his study (Bonhoeffer the Assassin?) a different journey for Bonhoeffer.

There are a number of very important biographies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, none more complete or significant than the one by Bonhoeffer’s friend, Eberhard Bethge (Dietrich Bonhoeffer: A Biography). Bethge’s biography is complete though not exhaustive (even if at times a bit exhausting) and takes serious commitment to finish. The prose is not captivating. Alongside Bethge is F. Schlingensiepen’s solid and recent biography (Dietrich Bonhoeffer). Those two describe a similar journey for Bonhoeffer (see below) while Eric Metaxas (Bonhoeffer) told a different story, a more evangelical one, which is why so many evangelicals have found Bonhoeffer in the last five years. Mark Thiessen Nation provides in his study (Bonhoeffer the Assassin?) a different journey for Bonhoeffer.

But one of the more fascinating, sometimes speculative and other times mistaken, studies of Bonhoeffer’s journey is now by Charles Marsh, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Why use the word “journey”? Because people have made meaning out of Bonhoeffer’s life and theological development according to the scheme they find in his story. The fork in the road or the place of decision is right here: When Bonhoeffer returned to Germany after that aborted visit to Union Theological Seminary in the summer of 1939, did his theology shift from a pacifist Discipleship and Life Together direction toward a more Niebuhrian realism/responsibility vision? That is, did he enter into the Abwehr (double agent) in Hitler’s National Socialist party as one who was seeking the downfall, assassination and replacement of Hitler or was his life as a double agent a ruse for his continued life in the ministry of the ecumenical movement?

The standard journey is the journey from a rather naive and optimistic hope for church renewal through intense commitment to discipleship toward a more realistic, even compromising, assumption of responsibility (this term is big in this discussion and must be connected to Reinhold Niebuhr at Union) all reshaped in his decision that the best way to act as a responsible Christian under Hitler was to assume the guilt of the nation and seek his country’s collapse. Maybe the best way of all to frame this is to say Bonhoeffer took leave of Discipleship by the time he was writing Ethics. That, at any rate, is the most common journey told of Bonhoeffer’s theological development. I have already covered Mark Thiessen Nation’s proposal and this post is about Marsh’s study, but it appears to me Bonhoeffer’s pacifism can remain in tact in spite of his realism since he saw entrance into the resistance as guilt (personal and national).

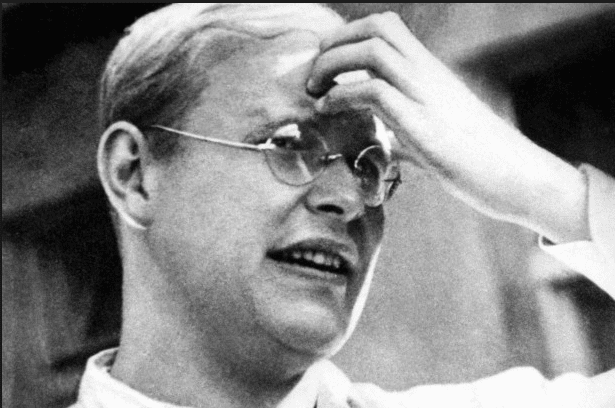

Bonhoeffer did come by his ecclesial faith naturally: his father was not a believer, his mother was and led family devotions in the evening, the family did not attend church frequently though he went through confirmation and was both spiritually and theologically curious when young, most of his siblings were not Christians, and even having completed his theology degree at Berlin (where as a liberal he encountered Barth) Bonhoeffer still was not much a church goer. His position as assistant pastor in Barcelona engaged him for the first time in serious church work. After his return to Germany he was committed to the church — but as much to the ecumenical church, to conferences, as he was to local parish ministry.

Bonhoeffer embraced Barth’s theology deeply and this is one reason for Marsh’s general approach to Bonhoeffer’s journey: Barth is present in his dissertation on the communion of the saints, in his habilitation on German philosophical history (Marsh thinks this book was “one of the great theological achievements of the twentieth century”), but it is profoundly present in Ethics. The first “chapter” of that book could be taken from Barth’s theory of revelation in dialectical thinking (and unfortunately dialectical method in writing!) in its unifocal concentration on God in Christ as the true revelation by which all things are measured — including the world. Furthermore, Bonhoeffer here has embraced some of Barth’s universalism for the thematic center of that first chapter is about the reconciliation (ontologically) of the world in Christ already. Marsh keeps Barth before the readers of Bonhoeffer’s life.

Bonhoeffer’s twin sister, Sabine, married a Jewish man (who had been baptized). That fact opens up a window that tosses light deep into Bonhoeffer’s theology: he was deeply committed to the brotherhood and sisterhood of the church and Judaism, of Christians and Jews, and therefore of Jews and Germans. When (Marsh’s portrait that) most were circling the wagons or wondering what was really going on, DB saw through to the heart of what Hitler and the National Socialists were setting up to accomplish in Germany and beyond. If he was anything, he was highly principled and so he refused to budge or surrender an inch to the National Socialists. (He was not as alone, however.) Bonhoeffer’s balking at both The Bethel Confession and The Barmen Declaration, the former he had an early hand in, concerned their lack of commitment to solidarity with Jews — believers or not. Seemingly ahead of everyone else in theological circles, including Barth, Bonhoeffer saw the Jewish Question as the Christian Problem. He helped his sister and brother in law escape from Germany to England through Switzerland. They survived the war Dietrich didn’t. Marsh’s Bonhoeffer is probing pluralism in affirmative terms, and Marsh is accurate.

Marsh has exceptional sections on Bonhoeffer in the USA fascinated by African Americans, their theology and spirituality (and songs), and this experience (at Abyssinian Baptist in Harlem) shaped Bonhoeffer’s thinking about what it takes to be a gospel Christian and what racism does to a people and nation. He not only introduced his students in Zingst and Finkenwalde to Negro spirituals, but he saw racism in Germany more intensively than others because of his time in NYC. No one is more attuned to racism’s impact on theology and the need to combat it than Charles Marsh, so his sections here are more sensitive and insightful than other sketches of Bonhoeffer.

Marsh, in my view, downplays Discipleship and Life Together because, again in my view, he sees a different journey for Bonhoeffer: it is one that sees the highlight years in DB’s life not in the outside-the-system seminary (they weren’t underground until the end) writings and spirituality but in the more “responsible” political theology of the Ethics and his Letters and Papers from Prison. His sketches of DB’s theology after his return to Germany and while in prison were a highlight for me.

In fact, Marsh has all but convinced me of the Christian realism move of Bonhoeffer. But before I will go on board officially I want to re-read Ethics and Letters and Papers from Prison, which I’m doing now. One thing has become clear to me: the conspirators were profoundly naive in planning to be those who would run Germany when Hitler was removed. Profoundly naive, if not delusional. I need to read more on this plot but that’s how it strikes me. [Later: I don’t think there is as much a break between the earlier works and Ethics as Marsh suggests, and I think Marsh needs to explore more what DB means by “guilt” and “vicarious representation” in DB.]

Marsh has reasonable control of the sources of Bonhoeffer’s life: he has obviously read them in German as well as in English (in fact I saw one or two mistakes in footnotes because he was referring to the German editions and not the English translations). Detail after detail is pressed from the original sources, in a historically chronological manner, and for this reason alone Marsh’s Strange Glory stands among the best of Bonhoeffer biographies. [However, I am hearing of some serious criticisms of Marsh’s comprehension of the German church situations, and this may do some serious damage to Marsh’s book.]

I must mention one feature of this book because if I don’t it will emerge in the comments and this short explanation allows me a bit of more accurate expression. Marsh’s biography is undoubtedly one of the easiest DB biographies to read (though nothing can replace Bethge’s fullness) but it will be remembered as the biography that suggested Bonhoeffer was gay or was romantically attracted to Eberhard Bethge. There is no explicit evidence; the relationship remained chaste; Bethge was engaged and then married and Bonhoeffer himself was engaged; there is Hitler’s extermination system that included homosexuals; and Marsh speculates on things without any evidence. There are suggestions according to Marsh: they shared a bank account, they shared Christmas presents, they spent constant time together, Bonhoeffer’s (not Bethge’s) endearing language in letters, Bonhoeffer’s getting engaged not long after Bethge got engaged, and Bonhoeffer’s obsessiveness with Bethge. OK, but it’s all suggestion, and this is complicated by Bonhoeffer’s obsession with clothing and appearance. [For a Marsh interview, see this.] Maybe he was and maybe he wasn’t, but it seems their relationship could at least be explored in another context: male friendships among German intellectuals of this era, which maybe needs the reminder that friendships have been between same sexes for most of Western history.

I quote here from Wesley Hill’s exceptional post on this topic about DB:

But, second, it also seems to me there’s an opposite danger that, in our effort to articulate and defend the existence of something like “close, non-sexual friendships between men” in past eras, we may overlook the importance of homosexual feelings in shaping those friendships. Yes, of course, “homosexuality” as we know it didn’t exist as a social construct until relatively recently, but that doesn’t mean the reality of persistent, predominant same-sex sexual desire didn’t exist and that it didn’t have a friendship-deepening effect for those who experienced it. Sure, Bonhoeffer wasn’t “gay” in our post-Stonewall sense. But what Marsh’s biography tries to explore is whether Bonhoeffer may have experienced same-sex attractions and how those attractions may have led him to look for ways to love his friend Bethge. Bonhoeffer evidently didn’t—and maybe didn’t even wantto—have sex with Bethge (and presumably Bethge himself wouldn’t have consented anyway). But did Bonhoeffer’s romantic feelings for his friend, if indeed they existed (as Marsh believes they did), lead him into a pursuit of emotional and spiritual intimacy with Bethge that he wouldn’t otherwise have sought? I think there’s a danger in avoiding that question, too, even as there’s a danger in jumping to the conclusion “Bonhoeffer was gay.” [Wes has a very good review of Marsh’s biography in the most recent edition of Books & Culture.]

In an earlier post on the same topic, Christopher Benson asked this powerful question with a brief comment:

Did Bonhoeffer ache for a romantic friendship with Eberhard Bethge or for the romance of a friendship that unites body and spirit, emotion and intellect? This is a distinction with a difference, and it is lost upon us because we are no longer in touch with “the tradition of late-antique and early-medieval Johannine Christianity, in which intimacy and understanding go hand in hand,” according to Samuel Kimbriel’s new book,Friendship as Sacred Knowing: Overcoming Isolation.

Perhaps then DB had same-sex attractions for Bethge but they were unreciprocated and the desires subdued by Bonhoeffer, but that those feelings had a “friendship-deepening effect.” That is at least a reasonable explanation of the letters between DB and Bethge. But there’s a bit more evidence that I had not known about prior to this post. In F. Schlingensiepen’s very complete and well-researched study of Bonhoeffer, on p. 393, there is a footnote in which Bethge responds to the suggestion that the authors of the letters (in Letters and Papers from Prison, most recent edition?) must have been homosexuals. Bethge says unequivocally Nein. [I am also convinced there is a dramatic difference at the level of intimacy in the letters to Maria and those to Bethge, so much so that one can easily argue the former is sexual and the former not so. I am finding Marsh’s case less than compelling and far too speculative as I continue to read.]

So maybe DB’s obsessions with Bethge deserve to be considered as expressions of a controlling, if not authoritarian, personality type. In fact, the Union professor, Paul Lehmann, said DB “simply took command, uncalculated command, of every situation in which he was present” (I Knew Dietrich Bonhoeffer, 42). Bethge himself said Bonhoeffer could sometimes be “imperious and demanding” (46).

Marsh knows that there’s some hagiography about Bonhoeffer, not least some of the descriptions of his last hours and minutes. He suggests Bonhoeffer was cruelly tortured for hours before he died.