Even the briefest encounter has the power to transform us, Gabriel García Márquez believed. Living in Paris in the late 1950s, he spotted Ernest Hemingway on the Boule Miche and, without thinking, yelled out "Emming-way!" The American did not look round, merely raised his hand. Yet the young Colombian writer interpreted his gesture as a blessing, a permission to continue—and eventually to leave us with some of the most enduring novels of the past century.

One of Márquez's themes was love at first sight: "Love is the most important subject in the history of humanity. Some say it is death. I don't think so, because everything is connected to love." About his own romantic passions, though, the author remained tight-lipped. He told his biographer Gerald Martin "with the expression on his face of an undertaker determinedly closing a coffin lid back down, that 'everyone has three lives: a public life, a private life and a secret life.'" When Martin asked if Márquez might give him access into the latter, he replied: "No, never." If his secret life was anywhere, he intimated, it was in his books.

This is why a brief encounter depicted in his collection Strange Pilgrims deserves pausing over. The story, "Sleeping Beauty and the Airplane," is about a meeting in Paris between the author and a Latin American woman who, as the day unfolds, is elevated into his muse. It opens with this indelible description:

"She was beautiful and lithe, with soft skin the color of bread and eyes like green almonds, and she had straight black hair that reached to her shoulders, and an aura of antiquity that could just as well have been Indonesian as Andean. She was dressed with subtle taste: a lynx jacket, a raw silk blouse with very delicate flowers, natural linen trousers, and shoes with a narrow stripe the color of bougainvillea. 'This is the most beautiful woman I've ever seen,' I thought, when I saw her pass by with the stealthy stride of a lioness, while I waited in the check-in line at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris for the plane to New York."

I remember reading this paragraph in 1992 when the book came out and being struck by the same thought as doubtless many others: I, too, wouldn't mind meeting this paragon. Aside from anything else, she was the mirror-fogging incarnation of every Márquez heroine, the type of independent, sassy, yet quintessentially innocent woman that we find boldly stalking through all his fiction, even the pages of his last novel Memories of My Melancholy Whores.

Then, this summer, not long after Márquez's death, I received an email from a woman living in London. She knew me to be an admirer of Márquez—she had read my introduction to the Everyman edition ofLove in the Time of Cholera. She wanted to tell me about a day she had spent with the Colombian author, in 1990, at Charles de Gaulle Airport: The experience, she believed, had informed his story "Sleeping Beauty and the Airplane."

In the autumn of 1990, the 63-year-old Márquez was back in Paris after a lengthy absence. He had been working since 1976 on a collection of short stories set in Europe about the strange things that happen to Latin Americans there—his only book that would have a non–Latin American background.

The idea for it originated in a dream he'd had in Barcelona in the 1970s, in which he attended his own funeral.

It was a joyful occasion; he spent time with friends he hadn't seen for 15 years, but when the moment arrived to leave, he was told that he was the only one who could not go.

The story explored another important theme in Márquez's fiction—the otherness of ourselves—and he intended it to be the third piece in Strange Pilgrims. In any event, he never wrote it, and its place would be taken by "Sleeping Beauty and the Airplane."

Márquez had scribbled down the Barcelona dream and other ideas in one of his children's notebooks between 1976 and 1982, when he had made a vow not to publish anything until Pinochet fell from power, and now, after toying with the stories for so long and suffering "an eleventh hour doubt.… I wanted to verify the accuracy of my recollections after 20 years, and I made a fast trip to reacquaint myself with Barcelona, Geneva, Rome and Paris."

At the very end of that trip, in early October 1990, he was waiting in Charles de Gaulle Airport to fly to New York when a ravishing 26-year-old Brazilian girl sat down beside him.

Meeting Sleeping Beauty

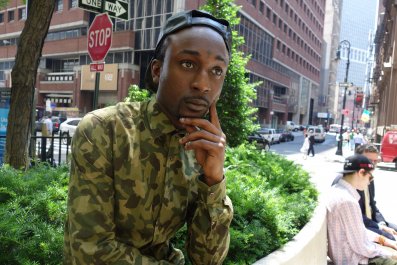

The woman who arrives, late, at the café in Notting Hill Gate is today a 50-year-old grandmother living in London. From her handbag, Silvana de Faria produces a passport and photographs of herself in French magazines, fully endorsing his description of her beauty. "At that time I was an actress," she says. "I am the queen of gaffes, and one of those was with him."

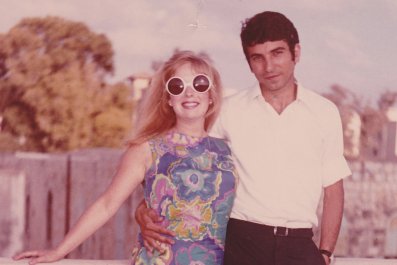

De Faria was living unhappily near Paris with a French film director, Gilles Béhat, by whom she had a 7-month-old daughter. Béhat apparently realized that De Faria was so unhappy that he paid for her parents to come on a visit from their home in Belém. At 9 a.m., she arrived at the airport to meet the Brazil flight.

It was a cold October morning, and she had lost her pregnancy weight. "I was very slim—nine stone—and concerned about how I was going to dress up. My mother always criticized me for being too provocative.… That's why I remember what I was wearing that day. I had on a leather jacket, a Kenzo blouse with flowers, pale linen trousers, and Kenzo shoes, red with flat small heels—later I gave them to Oxfam."

Unusually, De Faria was on time. "I run and go to the Air France desk and ask for the flight," say said. As in the story, the plane had been delayed by bad weather.

"Now I can relax. Then I noticed the airport was full of people. Many were sleeping on the floor. There were no seats anywhere—just one, and I sat on that. Thank god, I've found the only seat in the airport!"

It was now she noticed the man sitting beside her, 60-ish, good-looking, elegant in a tweed jacket, with tidily brushed hair and moustache.

"He said, 'Bonjour'. He had a wonderful smile. I'm obsessed about teeth. The first thing I look at is teeth. His teeth were white and perfect. I could smell his breath was very clean, because our chairs were close together."

"'Bonjour,' I said back.

"He looked at me, charming, shy, flirting. 'Are you waiting to travel?' he asked in French.

"'No, I'm waiting for my parents.'

"'Where are you from?'

"'Acre, in Brazil.

"'Is that near the Andes?'

"'No, it's on the Amazon.'

"He was very touched to meet a genuine Latin American in Paris, born in the Amazon forest. I said: 'When you are born in the jungle, you can survive anywhere. Living in a modern city is just a different kind of jungle.' Then I said: 'And you, are you going to travel or are you waiting for someone?'

"He didn't reply and I respected that. I thought: He is private.

Nonetheless, she asked if he might look after her handbag while she bought a bottle of water. "When I came back, I swallowed a pill, and I joked that I was like Elvis Presley, and showed him my pills, saying how colorful and beautiful they were.… Pills to sleep, pills to wake up, pills to smile, pills to lose weight, pills to gain weight, pills to make love, pills to make poo, pills not to make poo.

"'Why so many?' he smiled.

"I told him about a car accident in which I nearly died, and how my doctor gave me pills to 'calm down' and how I'd become addicted, but I was going to stop taking pills, as my parents were coming to stay with me. Then he asked why I was living in Paris. I said, 'We Latin Americans can only live in France when we fall in love.'

"'In love with France?'

"'No, love at first sight. I believe that's the only kind of love.' This is what he writes in the story! He sucked my words. [In the story, Márquez asks the check-in attendant "if she believed in love at first sight."] When I read that, I felt goose bumps. 'You are not original. You are like all bloody writers. You are a vampire!'

"He asked me what I did. I noticed he was staring at my hair, face, hands, body. I thought he'd try and take me to dinner and then to bed. I was so suspicious of men. You have a coffee, and they say they are in love with you. How can you be in love with me if you've just had a coffee?

"I tell him: 'You think because I'm a Brazilian, I'm a prostitute in the Bois de Boulogne'—I was paranoid about this because at that time all Brazilians in Paris were never students.

"'I didn't say that!'

"'But you thought it. I can read your thoughts.'"

She told him she was an actress and a singer, and her dilemma was that she didn't want to be either. "I want to be a student, but I find myself in the middle of show business. The real, real truth is I can't sing, but people say I can. They think I'm a good actress. I'm not."

He asked if she knew Ruy Guerra, the Brazilian director.

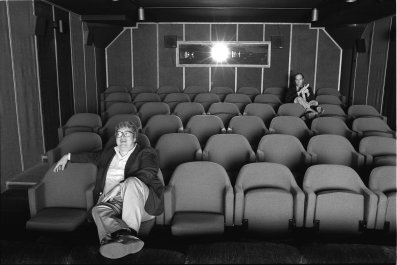

Her reply: "I just saw a film of his based on a story of Gabriel García Márquez." This was The Beautiful Pigeon Fancier, one of Guerra's three films of Márquez's work. "I was the only person in the cinema, which was a shock, at 2 p.m. in a room on the Champs Elysées, and I hated it."

"He was listening with attention and was a bit uncomfortable, and I didn't understand why. I said: 'Look, the film is made in Paraty, a place I know. Anyway, it's not possible in this world to adapt a Gabriel García Márquez novel into a film. It would have to be another genius. I'm sorry if you don't agree with me.'"

His interest in De Faria had quickened. She says: "At first, I think he thought I was crazy. Now he wanted to know where I came from, about my family, and I told him all the bullshit he wanted to know."

The Real Silvana

In Márquez's story, no word is exchanged between him and the young woman, with her ancient Andean features, her Japanese-style clothes and the pills that she takes to make her sleep, and who turns out to be occupying the next seat on the eight-hour flight, before she disappears into "the jungle of New York."

Yet in another dimension, Márquez knew everything about her—because before the flight, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., they had talked nonstop, "keeping eye contact all the time," she says, "which was important for me." And what Silvana de Faria unveiled to him during that period, not realizing his identity until the last moment, was a distillation of the women he felt compelled to write about.

"The reason I think he and I became talkative and 'close' that day is because I delivered everything he wanted. Any question, I answered. No limits."

She was born in Rio Branco, in Acre, the youngest of 10. Her family on both sides were rubber planters. "They became rich, rich to die. Their clothes were washed in Europe because the color in the river was too dark."

Her dream since the age of 7 was to go to Paris. "I realized the only way to get to Paris was by plane. I studied law in Belém and then looked for a job. I found one in Varig, the airline office. At the end of one year, I would be able to buy a 10 percent ticket. Then one day I get a call. 'I am the secretary of John Boorman.'

"'Who is he?'

"'He's a very famous film director. His assistant came to buy a ticket and met you. He's looking for a girl with your face.' He was shooting The Emerald Forest. But on the final day, he changed his mind and took another girl, and I'll hate this girl to the last minute of my life, till I have oxygen. I didn't want to be an actress. I wanted money. I cried.

"John Boorman said: 'Why do you want the part?' 'Because I want to go to Paris.' 'Why?' 'To study.' 'OK, I give you a small part in the film.' I was one second in the film, an indigenous mother with a baby. On July 11, 1984 the film is finished. On July 14, the day of the French revolution, I put my feet in Paris. Vive la revolution!"

Awarded a place at the Sorbonne to study history, De Faria modelled to pay her way. One day, she was spotted by a scout for Yves Saint Laurent—she had the exact look he was selling to Japan. Could she sing? "Like a pressure cooker," she replied. She was invited to audition with hundreds of others. "I got it! But I wasn't a singer! I did a record Coeur Bongo. You can watch it on YouTube." Recorded in 1988, Coeur Bongo shows De Faria to be the lithe lioness of Márquez's story. She signed a contract to make five pop records, was taught how to act, did three television shows, and stopped studying.

"I never finished the Sorbonne. It's the pain of my life."

Plus, she'd met Gilles Béhat. The film director had come into her manager's car, where she was sitting, to hear a soundtrack. "We looked at each other and we fell in love. Love at first sight!"

Their relationship would be violent and passionate. "We had terrible, jealous fights." After two years, they moved out to a large house in Richarville, about 25 miles from Paris, with 12 dogs—and a parrot, because De Faria missed the Amazon. "He gave me a parrot, and he gave it the name—Antoine. My friends said: 'The parrot is not the Amazon, the parrot is you. You are living in a cage.' That's when I start playing with pills."

All this she told Márquez.

Love at First Sight

"After one or two hours, it was like we were at primary school together, mixing Portuguese with French and Spanish. We were talking, joking, laughing. I wasn't seeing an old man."

As for Márquez, it is evident from what he wrote afterward—"in eight feverish months…to achieve the volume of stories closest to the one I had always wanted to write"—that he was seeing, as he put it, "the most beautiful woman I've ever seen."

De Faria says, "I am and was in shock that I could recognize our conversation."

Love at first sight, passion, coincidences, cinema, family values, Paris, even star signs—in seven hours, they covered the gamut. "I told him I am a Leo with Taurus ascendant. That was the reason I was strong enough to struggle with living in Paris. He said he sometimes wished he was a Taurus. And he says so in his story!" ["Damn it," I said to myself with great scorn. "Why wasn't I born a Taurus?"] He himself was a Pisces. "I said Pisces are always dreaming, in imagination mood, always swimming—and I made a mouth like a fish, which made him laugh."

By now, it was 4 p.m. "I was concerned about the plane, my parents. What if the plane had disappeared? We started to talk about death, about dead people.

"He asked: 'What do you think will happen to you when you die?'

"'I will become a ghost, free, and then I will come and scare you. But why from the beginning do you only ask about me?'

"He said: 'What do you think I am, and where do you think I'm travelling?'

"'As far as I know, you've been travelling through my body, but I don't know where you'll finish.' He laughed: 'I'm amazed by the sincerity that comes from your mouth!'

"'At least, I'm not scared of words,' I said.

"'I'm a journalist.'

"'Which paper?'

"'I don't work for papers.'"

It was then that De Faria woke up to who he was. "I looked at him and, shouting, I said: 'I know you. You are Gabriel García Márquez! My mother gave me Love in the Time of Cholera, and it has your picture! Why didn't you tell me it was you?'

"'How was the picture?'

"'Men! You're all the same. All is vanity.'

"I felt embarrassed and upset and betrayed. I realized that's why he didn't want to talk about himself—because he had not said a word, even when we talked about Ruy Guerra and his film. He had not said, 'I wrote the story and the script.' I was confused and wanted to leave.

The plane had landed, my parents were arriving. 'I have to go.' But he grabbed me firmly by my arm and stopped me. He asked for my Filofax and wrote in it.

"'For you, I am Gabo. Here is my address and telephone and fax.'"

She fishes a lined page from her bag and there it is, in red ink: GABO. MEX. Fax 5686043 Tel 5682947. Ap Postal 20736. Mexico, 01000

"He said: "Please. Write me,' looking straight into my eyes.

"'I have to go!'

"You are going to write, aren't you?'' Then: 'I don't even know your name!'

"'Did you tell me yours? We spent this whole time together, we know each other so well—and we didn't know each other's name.' And I left."

After that, De Faria says, she simply forgot him. "I lost trust, in a way. I didn't read any of his books again. I never had the desire to call him or write to him.

"Then when he died, I found this story of the airport."

"And when you read it?" I ask.

"I felt his tone and his voice. I had the feeling of him looking at me, staring. I felt for a few minutes he was sending me a message."