“What Am I Paying For?”

It was a bold new idea: an all-sports college, classes be damned. But for the athletes at Forest Trail Sports University who faced hunger, sickness and worse, it turned into a nightmare.

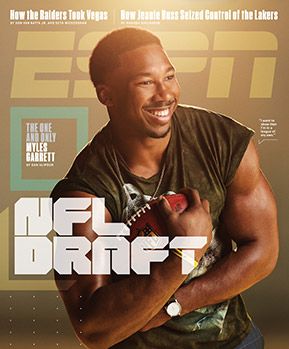

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's April 24 NFL Draft Issue. Subscribe today!

The players are changing into their uniforms in the parking lot. The opponents are the Virginia Marlins, representing the University of Virtual Applied Athletics in Danville, Virginia. The crowd numbers three dozen, if you include the dogs sitting in the concrete grandstands, which are only slightly harder and grayer than the infield. In every way, the scene suggests the lowest possible rung of competition.

Yet the rhythms of opening day -- muscles twitching, bats swinging, adrenaline pulsing -- are particularly exciting for the group of 20 college-age athletes gathering behind the third-base line. "It's liberating," says Nick Roets, 19, of Wingate, North Carolina. "We didn't know how this was going to turn out, but we knew that getting out of there was in our best interest."

"There" was Forest Trail Sports University, which promised a new kind of college experience, focused on athletics. And these players -- they have named themselves the Renegades, but Refugees would be just as accurate -- are survivors of its collapse. Arriving last August at the for-profit program, which charged a tuition of nearly $33,000, they were consigned to an old hotel, without adequate facilities, staff or supervision, on a campus where the threat of violence turned out to be more common than classes.

All the players taking the field have a story: The 6-foot-5 lefty starter had come to FTSU looking for another shot at impressing scouts but was rebuked for trying to eat more than a single Pop-Tart for breakfast; the second baseman found himself taking BP on a caged-in tennis court knotted with tree roots and branches; the third baseman discovered holes in his bed and mold in the air conditioner.

And as the story of Forest Trail's implosion makes clear, the baseball players were the lucky ones. Athletes in most other sports were abandoned by their coaches. Some had to deal with serious injuries without being able to get proper treatment. None played anything like a full schedule of college sports.

"Forest Trail messed with our families, our money and our emotions," says Anna Roets, Nick's mother. "These kids have been to hell and back."

When Forest Trail Sports University first made headlines last spring, it was for a concept as simple as it was startling: sports without school. As its website put it: "FTSportsU does not offer instruction, tutors, records, certificates or degrees. ... The mission of FTSportsU is to provide varsity and recreational athletics to all of our students."

From Apex Tech to Trump University, for-profit schools have enjoyed periodic surges in popularity, often with dubious results. Research shows that, on average, they charge higher tuition and pile more debt onto their students while having lower graduation and employment rates than nonprofit schools. A few field college sports teams -- Grand Canyon University is an example in Division I.

Forest Trail was something new: Gifty Chung, a Ghana-born education entrepreneur, was launching a program that she branded as a university and that offered athletics but no teachers, libraries or curriculum of its own. Athletes would pay to play sports year-round and live on campus. They would study online, through classes provided by Waldorf University, a school based in Forest City, Iowa.

The 42-year-old Chung, who has a Ph.D. in education and educational leadership from the for-profit online University of Phoenix, was already operating two businesses named Forest Trail Academy. One was an online K-12 school in Wellington, Florida, founded in 2007; the other, a prep school in Kernersville, North Carolina, centered on a basketball program run by former Wake Forest and NBA player Delaney Rudd, launched in 2015.

Later that year, as she thought about expanding toward college, Chung began working with Luis Cortell, a soccer coach at the West Virginia Institute of Technology. "Imagine if you had to travel with your team but never missed any classes," he says.

Chung officially incorporated the school, initially called North Carolina Sports University, in January 2016. Cortell, who became its first athletic director, thought the school could rent space from Barber-Scotia, a historically black college in Concord, just outside Charlotte, that had fallen on hard times and shut down classes. He wasn't a financial expert but figured that if he and Chung could get 200 students to fill Barber-Scotia dorms, it would cost about $11,000 per athlete per year to provide them with accommodations, three meals a day and tutors. They could play and train at Barber-Scotia's fields. And maybe kids who hadn't landed scholarships out of high school would get another chance to boost their grades and their exposure.

Chung and her husband and business partner, Riko, liked the plan but not the price point. "We can't charge that and break even," they said, according to Cortell, and mentioned setting yearly tuition around $18,000, about 15 percent higher than the national average at for-profit colleges. They also suggested it might not be necessary to work with Barber-Scotia. (Gifty Chung declined multiple requests for an interview. She submitted a statement, which is quoted in relevant sections below. Riko Chung declined multiple requests for an interview.)

"I was taken aback," Cortell says. "Understand, I was trying to do something for students, and they are businesspeople trying to do business. Forest Trail picked up my idea and changed it to make money." Cortell left FTSU early in 2016 and now coaches at Shaw University in Raleigh.

Greg Eidschun, who was already serving as FTSU's baseball coach, then stepped up as AD. Eidschun, 52, pitched at Fresno State and went on to run Athletes for College, a Carlsbad, California, company that connects high school athletes with college scholarships. He was excited enough about Forest Trail to move his wife and family east. "I was going to be targeting and recruiting athletes," he says, "who had received no other scholarship offers and who really were looking for a home."

Particularly the way Eidschun framed the pitch, the Forest Trail idea had enormous appeal to high school athletes who hadn't quite demonstrated the combination of skills and grades to land a scholarship but who desperately wanted to hang on to their dreams -- and it resonated with their parents too. Maybe a grad just needed another year or two to grow into his or her body. Or to fine-tune a mechanical adjustment. Or to buckle down and study. Or just to get noticed by the right D2 coach. Who wouldn't believe that about their kid?

"We had several visits and coaches coming to games, but we did not receive any other offers," says Mark Reynolds, a real estate agent from Gainesville, Georgia, whose son Kyle is a pitcher. "Then Greg came through with his offer from Forest Trail. I did some research on the internet, and it looked like a really legit website. I knew my boy would be taken care of."

Gifty Chung's charm helped reel in recruits. "She told us about how she was going to be Kyle's second mama," Reynolds recalls. "About how once Kyle got up to Forest Trail, she would take care of him."

"She hugged me and she told me she had children, and she went into my heart," Anna Roets says.

By late spring, Forest Trail was expecting 200 to 250 students to arrive in the fall and planned to offer up to 10 sports, including baseball, men's and women's basketball, cheerleading, soccer and track and field. Tuition was listed at $32,700 a year.

Delaney Rudd (center) and Gifty Chung (right) at a prep basketball game. ESPN

Youthful in appearance, with bright eyes and a ready smile, Gifty Chung connects easily. "She's terrific in every way," says Carolyn Tribble, who runs a tutoring service in Wellington, Florida, where Gifty worked in the mid-2000s. "Kids loved her, parents loved her, other tutors loved her. She was ambitious and upwardly mobile -- she was working on her advanced degree while she was working here."

Her husband, Riko Chung, is a murkier presence. Staff at both Forest Trail locations were sometimes unsure of his role at their schools, with a few even saying he had none. But Riko is listed as chief operating officer on the website of Forest Trail Academy in Florida, and internal correspondence obtained by ESPN makes it clear that he was deeply involved with many of the university's business operations.

As it turns out, there were urgent reasons to question the Chungs' trustworthiness and business acumen. For one thing, in August 2007, U.S. marshals arrested Riko Chung as part of a multiagency crackdown against online pill mills. Chung, now 47, pleaded guilty to two counts of illegal distribution of controlled substances and money laundering. He was sentenced to two years of probation and agreed to pay a settlement of $864,898, the government's estimate of his share of the scheme's proceeds.

Public records also show that the Chungs failed to pay more than $25,000 in income tax in 2006, nearly $70,000 in 2007 and $150,000 in 2010. The IRS slapped a $95,273 lien on them in 2009 and another for $93,581 in 2011. With mortgages, bank loans and credit cards piled onto those debts, the Chungs owed more than 30 creditors nearly $3 million by 2013 and had just $668,508 in assets. In April 2013, they filed for bankruptcy.

Further, Gifty Chung either didn't know or didn't care about some of the basic legal requirements for operating a for-profit university. In an interview with The Chronicle of Higher Education, for example, she said she didn't think Forest Trail needed a license. That was incorrect. In June 2016, the University of North Carolina board of governors told FTSU and Waldorf University to "cease and desist" from "post-secondary degree activity." That was enough trouble for Waldorf, which terminated its partnership with Forest Trail on June 17.

Forest Trail's deal with Barber-Scotia also fell through, and just before students were due to arrive, the program moved 65 miles to the north. FTSU would share space with the Forest Trail prep academy, home of Delaney Rudd's basketball program. Rather than living in the Barber-Scotia dorms and playing on its fields, athletes would occupy a desolate stretch on the industrial side of Kernersville. They would move into the Phoenix, a recently closed hotel near the academy and its gym.

Eidschun reached the campus on Aug. 1, after driving cross-country. "I was told by Delaney Rudd, 'Don't worry about it,'" he says. "But the rooms were a mess, completely torn up. It was a disaster."

Rudd claims the assurances ran in the opposite direction. "I never contacted, promised anything or spoke to anyone leading up to their arrival. Greg was on commission and was bringing kids in that we had no clue about and was putting them in rooms without asking us," Rudd said in a statement. (He declined multiple requests for an interview.) "Then when we approached him about it, he would say, 'It will all be OK.'"

Relocating on such little notice cost Forest Trail a chunk of the athletes the program was expecting and confused plenty of others. "I actually went to Barber-Scotia, and no one was there," says C.J. Cecil, a baseball player who flew in from San Diego. "I had to text them and be like, 'Where's the campus?'"

Most moved in, however, despite any misgivings. "There was nothing around, but I thought, 'Well, maybe they have some place they go for baseball,'" says Anna Roets, who arrived with her son on Aug. 15. "And Nick was super excited. He didn't even say 'I'm going to miss you guys.' He was just so pumped, and that made me feel that he was OK."

But there were hardly any places to play outdoor sports at America's first sports university. Forest Trail put up two goals on a stretch in front of the school to improvise a soccer pitch, and athletes from various sports were left to practice there. "We'd use the corners as home plate and take infield," says Nick Roets, who plays second base. "Whenever we wanted to hit, we would have to go to a state park down the road and make do with a softball field there."

Diamonds weren't the only fields missing. "There were no track facilities, actually," says Jordan Miller, a sprinter from Temecula, California. "We trained on that patch of dirt they use as a soccer field."

Meanwhile, Forest Trail's housing was crowded and filthy, according to athletes and staff. "We had to basically just build beds or throw mattresses in anywhere we could and try to fit people in, where there would be four to a room," Eidschun says.

"When I moved in, it was dirty before I got there," says Purnell Chaplin, a baseball player from Columbia, South Carolina. "The box spring on the bed had a hole in it, so I was sleeping uncomfortably. I realized there was mold in the air conditioner."

"Those dorm rooms were nasty," says Tiana Douglas, a basketball player from Long Beach, California. "And in the bathroom, the tub was dirty, underneath the sink was dirty. One guy flooded his restroom, and no one came to clean it up."

“My dad, who's in prison, is eating better than we were

at that school.”

- Jordan Miller, former Forest Trail athlete

Students say the food was even worse. In both quantity and quality, meals such as single servings of Pop-Tarts for breakfast or microwavable corn dogs for dinner failed to meet the needs of growing athletes. "I was disappointed because I like to eat a lot," Cecil says. "I was just going with it because I was there to play baseball, but over time it got really bad. One day, I went into breakfast and I grabbed one of my Pop-Tarts, and I also tried to grab a small package of muffins. And the guy who worked there yelled at me and took the package out of my hands. He made me apologize for taking the muffins."

"We didn't have a protein, a starch and a vegetable; it was just, 'Here's pasta,'" Douglas says. "They used to lock up the sodas and the juice and then give us one container of water. We needed more than that. They had a salad bar, but it was a bar with nothing in it. Fruit was there, but it was constantly going bad."

In his statement, Rudd said, "The food was catered daily, and like in any program, the kids may or may not agree with the serving amounts."

"Let's just say my dad, who's in prison, is eating better than we were at that school," Miller says.

As hard as it was for athletes to stomach Forest Trail, it was even harder for many to complain to their families. "My parents put so much time and treasure into me going to Forest Trail, it would have been difficult to tell them, 'It's not working, I want to come home,'" Cecil says. "So I just tried to stick with it. I tried to make the best of everything."

"My mom said, 'I think you should come home,'" Nick Roets says. "I was like, 'Mom, I can make it. No matter what goes on, I can overcome it.'"

Since the collapse of Forest Trail, keeping the baseball team going has not been easy. Carrie Shelley, coach Greg Eidschun's daughter-in-law, helps cook for the athletes at their new dorms in Greensboro. Lexey Swall for ESPN

As a business, FTSU was caught between contradictory imperatives. According to internal emails, the Chungs intended to spend less than a third of tuition revenue on school operations -- something like the $11,000 per student per year that Cortell originally calculated -- and apparently planned to invest the rest elsewhere or keep it as profit.

But Eidschun -- who, like all of FTSU's coaches, was working on commission -- had recruited many students by offering them hefty scholarships, ranging from $10,000 to $25,000 a year. Moreover, whatever athletes or their families were going to pay, most didn't have it on hand. Instead, at Forest Trail's urging, they applied for loans, a process that takes time and was complicated by the fact that the program had to switch online-education partners.

"Only a few of the students paid the full agreed-upon amounts," Gifty Chung said in her statement. "After recruiting the students, Mr. Eidschun directed them to move into the dorms. He had sole supervisory responsibilities and kept all the money he received for recruiting." (Eidschun says he never received the commission fees he was promised.)

By the fall semester's start, FTSU hadn't generated nearly the cash the Chungs were expecting -- or what it would have taken to properly run the school.

"So far, we have brought in about $70,000, of which 28% goes back to the program," Riko Chung wrote in a long email to Forest Trail's staff and coaches on Aug. 24, less than four weeks after athletes started arriving on campus. "This is barely enough to feed the athletes for 2 months."

Given Forest Trail's finances, Riko had no time for complaints. "These athletes are NOT paying $32,700 to have buffet or similar meals," he wrote. "$32,700 is a FAKE number. ... Majority have only paid their deposit. TWO students have paid their entire tuition. We should not put much into their complaints about food, housing, equipment, internet, etc. ... They are lucky to have a room."

He told the staff that it had cost more than $70,000 to upgrade Forest Trail's gym. "Please so [sic] NOT leave athletes in their [sic] alone," Riko wrote. "They should be monitored at all times." He also instructed them to get students off Netflix and YouTube during the day: "I don't have to hear any complaint about slow Internet."

He concluded by expressing the toll FTSU had taken on him and Gifty. "I, personally, am too busy with our business in Florida to deal with all this nonsense," he wrote. "My wife is stressed. She can't sleep and sacrifices a lot for this project."

But most students interviewed for this story had no idea who was running the campus from day to day. Supervision was light. Riko Chung's Aug. 24 email asserted that within two weeks of the program's launch, incidents occurred involving athletes drinking, smoking pot, driving while intoxicated and even brandishing knives. In his statement, though, Rudd said, "We never found any proof of this when we researched it."

At least some of that behavior involved the FTSU handyman, Karl Surgeon, 46, from Greensboro.

"We would have parties, and Karl would find his way in and play beer pong," one FTSU athlete says. "Some days, it was like he couldn't do that because it was against the rules, and then the next day he would just come anyway."

In addition, at least two students say that Surgeon told them he had the authority to check their rooms unannounced for the presence of unauthorized people. "That wasn't OK," one student says. "I'm a woman, and you can't do that."

Surgeon has had 29 criminal incidents over the past 27 years, the most recent for an offense unspecified in public records that took place at Forest Trail's address last Aug. 23. In 2003, Surgeon was convicted on three counts of possessing a Schedule II controlled substance, a group of drugs that in North Carolina includes cocaine and methamphetamine, with intent to sell, and he received a suspended sentence and probation. Students say that Surgeon liked to boast about his past drug-dealing. He did not return calls seeking comment.

Riko Chung defended Surgeon, whom he called a "committed and loyal" staff member.

In his statement, Rudd said, "We did not ask him to enter a room unless there was a maintenance issue."

In September, an infection hit Forest Trail and spread quickly through the baseball squad, like croup among prison inmates. Over two weeks of coughing and vomiting, Roets shed 8 pounds, Chaplin lost 10, Cecil dropped 12. Some of their teammates even wound up in the hospital, according to their coach. "We had 40 baseball players, and four would come out to practice, because everyone else was severely sick," says Eidschun, who also came down with the bug. "I think when you get that many people spending so much time in those rooms that were so small, and not being provided the things they needed, that's what happened."

But, contradicting public declarations by Gifty Chung that "safety is a concern" and FTSU would hire "superb" athletic trainers, students allege that Forest Trail devoted very few resources to medical or orthopedic care. Students say they couldn't find trainers. Some had to contend with coaches who were leaving and getting replaced and who had little understanding of their personal profiles. And in at least one case, a devastating injury occurred.

Jordan Miller, the sprinter, spent the spring and summer of 2016 working intensely to recover from a torn ACL before arriving at Forest Trail on a scholarship he believed was worth $22,800 a year. In Kernersville, he found not only that there weren't any track facilities but that there weren't enough runners for a track team. Miller had four different coaches within a month, and the third ordered him to lift heavy weights even though Miller had said he wasn't ready to plant and twist at the same time.

"I was squatting, and I went down and I heard a pop, and then my knee locked and I was just going down," Miller remembers. "It took everyone there a good five seconds to realize I couldn't go back up, and that's when they rushed to help me. Then they fought over who was taking me to the hospital, and that took an hour for them to decide."

Miller had reruptured the same ACL he had injured the previous year and suffered severe tears in the lateral and medial collateral ligaments of his left knee. And there was no way for him to rehab at Forest Trail. "There wasn't even a medical staff on campus," Miller says. "Basically, all they had was an ice machine, to put ice on whatever hurt."

After his injury, Miller says, he confronted Gifty Chung. "What am I paying for?" he asked. "There's no program. There's no education. I don't even eat here, to be honest. I sleep in the dark, so what electricity am I wasting?"

"They couldn't answer that," Miller says. Instead, the school told him he could pay or leave. His mother didn't have the money to fly him home. "But to them," Miller says, "that meant if you can't afford to go home, then you definitely can't afford to stay here." FTSU kicked him out; he stayed with a local friend until his family could buy a plane ticket.

Eidschun visits players in their new dorms in Greensboro. Lexey Swall for ESPN

When some students left and others just stopped paying, FTSU's finances spun even deeper into a death spiral. "This crap is milking me dry," Riko Chung wrote in a Sept. 20 email to Eidschun, copying Gifty Chung and Rudd. Riko was tired of waiting for loans to come through and didn't understand how freeloading students could complain about anything FTSU was providing. "Nonpaying athletes needs [sic] to go. ... If they think hotdogs were an issue," he asked, "what will they think when NO food is served in month #3?"

Riko was ready to get rid of any athletes who hadn't paid up, writing, "They can complain about hotdogs and nachos, protein, fruits and vegetables at their home." And he was willing to throw them off campus. "If we need to," he wrote, "once we have the list that needs to [go] home (and they refuse) -- call the police and have them escorted off for trespassing." He then wanted to herd the FTSU students into one end of the Phoenix Hotel, clearing space for prep students on the other. As he put it: "We need to kick kids out, pack the rest of them all on one side with 4 to a room.

"Again," he told Eidschun, "I don't care about the media, lawsuits, etc. None of these pay my bills."

Eidschun had served as the face of Forest Trail Sports University as loyally as he could, acting as a go-between among students, families and the administration. He really did believe program-saving cash would soon arrive in the form of loans. And while other coaches were abandoning FTSU, he went to extraordinary lengths to care for his baseball players. Parents still talk with a touch of wonder about how "Coach Greg" drove the team bus 10 hours to a doubleheader at Freed-Hardeman University in Tennessee -- and how, after their hotel declined the credit card FTSU had given him, he paid for their rooms out of his own pocket. "Right then and there, I knew we had a saint," says Mark Reynolds, whose son Kyle played on the team.

But Eidschun also had parents calling him constantly. And new problems kept cropping up; the latest was that athletes were going weeks without washing their clothes because the on-campus laundry was out and they had no transportation to go anywhere else. Eidschun was tired of rationalizing Forest Trail's conditions -- "I was always thrown out there to do the dirty work," he says. But he couldn't blame upset families. "If it was my son in that environment," he allows, "I would have pulled him."

One by one, Eidschun watched his players pushed near their breaking points. For Nick Roets, it came when he found himself trying to throw baseballs in a caged-in tennis court overgrown with tree roots. C.J. Cecil said he knew he wasn't right after he was sick nonstop for two weeks. Then Gifty Chung told Purnell Chaplin to pack his bags and leave, even though his mother had been making monthly payments to Forest Trail, he says.

"I was thinking, 'I can't just live on the street,'" Chaplin says.

On Oct. 21, trying to forestall the Chungs' summary evictions, 11 members of the baseball team went with Eidschun to the Kernersville Police Department and gave statements about Forest Trail. Later that day, a town official inspected the FTSU dorms. He found 14 housing code violations, such as broken smoke detectors, hanging electrical cables, an exit door off its hinges and two breaches of the local "unfit for human habitation" ordinance: defective air conditioners and potentially serious ceiling leaks. The town ordered Gifty Chung to report to a hearing to establish a timetable for repairs.

The Kernersville police also paid a visit. "I talked with Delaney Rudd and Gifty Chung and told them they couldn't kick kids to the curb," Detective C.D. Tucker says. "They said money wasn't coming in and that they were shutting down sections of the so-called campus. I said, 'You're going to have to evict them.' There's a process. And also, we can't have 40 kids on the corner, running loose in Kernersville."

Faced with multiple investigations and possible lawsuits, the Chungs folded quickly. By early November, they negotiated deals with a group of athletes and their families. According to a settlement obtained by ESPN that appears typical of the others, FTSU paid back several thousand dollars of tuition in exchange for the athlete giving up all claims against Forest Trail and keeping the terms confidential. By Feb. 1, the sports university was out of business altogether.

In her statement, Gifty Chung compressed the timeline of Forest Trail's downfall and blamed the athletes: "When online courses through Barber-Scotia College and other schools fell through, we realized that the college program was no longer viable. Meanwhile, the students had caused severe damage to school property. With student fees not forthcoming, we were forced to begin a process to evict these athletes from the residence halls. In an effort to resolve this experimental program in good faith, we returned all the money that had been paid to FTSU and entered into confidential settlements with the athletes' families."

Seventeen athletes received tuition refunds totaling $86,737, according to Gifty Chung's statement.

"On my way to pick up my son from this hellhole, it ran over and over in my head how Gifty played me, mother to mother," Anna Roets says. "I realized this is why people snap. I posted on Facebook that if I ended up in jail, not to bring me a file or bail me out, just a really good bottle of wine or my protein shakes. Because I'd be fine with it."

But neither the athletes nor their families got any chance for a final confrontation with Forest Trail's leaders. After Gifty Chung promised Mark Reynolds she would be a second mother to his son Kyle, he never saw or talked with her again. "I'd like to ask her about that," he says. "The only thing I can think of is that they brought him out there for one reason, and that was to get money. And then once the parents found out and weren't coming up with any more money, it was time to shut that thing down."

Members of the former Forest Trail baseball squad have somehow stayed together as a team. Lexey Swall for ESPN

Remarkably, FTSU's BASEBALL team, with no home and no budget, stayed together, with Eidschun. "I knew a lot of the other athletes," Chaplin says. "They left because their coaches weren't like our coach. After a while, they started giving up. Our coach stuck with us the whole time, through everything."

Forest Trail's other recruits have scattered, some carrying deep scars. Jordan Miller, now a student at Palomar College in San Marcos, California, is trying to run again but still wears a leg brace from his knee injuries. Tiana Douglas now shoots hoops alone at El Cerrito Sports Park in Corona, California, pondering her next steps. "I've always loved the game, but this did mess me up on what do I do now," she says. "I had worked my whole life for an opportunity to play basketball, and that was taken from me. I was going to be the only one in my family who made it to a university off a scholarship, and they kicked me out of a school they asked me to come to."

The Forest Trail concept is likely to resurface, and the officials who cracked down on FTSU may have shown how that's possible. The North Carolina board of governors stopped Forest Trail from offering college classes without a license but didn't take any further action -- which means the less education a so-called university offers, the less it can be regulated as a school. The Kernersville police took a closer look at Forest Trail after Tucker, the detective, met with Gifty Chung and Rudd, as did the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigations. They probed for financial aid fraud, but both agencies determined that because FTSU did not receive financial aid directly from a government agency, the issues between the business and its athletes were a civil matter -- that is, a private dispute over promised services -- rather than a criminal one. Which means the more financial burden a university can persuade students and their families to carry, the less liable it is for fraud.

So Gifty and Riko Chung are free.

Meanwhile, the for-profit education industry could be primed for a new boom. On March 6, President Donald Trump's administration began loosening federal regulations on for-profit colleges, allowing them to delay reporting whether graduates are able to repay their loans. Trump had previously faced lawsuits alleging fraud at his Trump University, reaching a $25 million settlement with plaintiffs just days before taking office.

The refugee Renegades made it through the winter, finding dorms in Greensboro and living off parent donations, Eidschun's savings and Kickstarter funds. They booked a 17-game schedule against local schools. And on that opening day, on that hardscrabble field in Danville, in front of those three dozen fans, they swept a doubleheader.

"There's still hope," Eidschun says.

"At what level, we don't know. But for these guys, there's still hope."