Born with a voice to die for and a runaway father who follows him everywhere, Jeff Buckley’s wish not to discuss the late, great old man contradicts his usual vocal dexterity. But like all good journalists, NME’s Ted Kessler gets him to spill the beans as well as discuss the emotionally laden musical nuances of his haunting album, Grace.

The London end of the line goes momentarily dead. The PR is stunned. Maybe she just didn’t understand what they were saying. Want to run it past her one more time?

“Sure,” comes the managerial response in New York. “We’re thinking of faxing you a list of questions that journalists shouldn’t ask Jeff. What do you think?”

Nope, she heard correctly. OK, what could these questions realistically be? What subjects are just too painful for the delicate ears of singer/songwriter Jeff Buckley?

“Well, no questions about his personal life for a start.”

Could be tricky, but we can work around it. Anything else?

“Yes. We want no mention of his father.”

Right. Don’t mention Tim Buckley when you meet Buckley Jr in the stockroom beneath The Point nightclub in Atlanta, Georgia. Forget any vocal lineage. Don’t even think of comparing the way Jeff Buckley’s voice can convey inner torture and unbridled joy within the same twist of a line and Tim’s ability to blast holes in walls with his pained wail.

Don’t look at a song like Last Goodbye by Jeff and compare its forlorn message of failed love (“This is our last embrace / Must I dream and always see your face?”) with, say, Once I Was by Tim (“Once I was your lover and I searched behind your eyes for you / And soon there’ll be another to tell you I was just a lie”). Don’t compare notes on their souls.

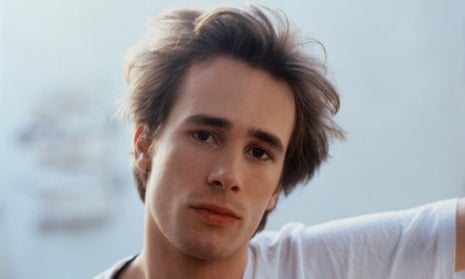

Don’t consider telling him that Grace, his fully-fledged long-player, is richer than his father’s eponymous first album. That it could be as good as his dad’s best work like Happy Sad – in parts even stronger because the songs are more rounded. Don’t pull out an old photo of his father in his mid-20s and exclaim: “Those cheekbones, those eyes, that smile – it’s really uncanny!” Whatever you do, don’t dwell on the fact that two of the great white American singers of the past 25 years just happen to be father and son.

Stop it. Don’t even think about it. Jeff doesn’t want to know.

“I knew him for nine days. I met him for the first time when I was eight years old over Easter and he died two months later. He left my mother when I was six months old. So I never really knew him at all. We were born with the same parts but when I sing it’s me. This is my own time and if people expect me to work the same things for them as he did, they’re going to be disappointed.

“Critics try to pin so many different inaccuracies on me and my music, they look at the complicated things and try to simplify them. They think they can nail your whole life down just by knowing the bare bones of your history in partaking in 10 minutes of conversation. If you’re going to write, then write a novel with a Haitian woman in it and try and describe her accurately. When you can do that, you can write about people.”

He is not Tim Buckley. He is not Dweezil Zappa or Julian Lennon. He is Jeff Buckley and, frankly, he’s had enough of talking about his father, the legendary late-60s, early-70s balladeer who died of a drug overdose aged 28 in 1975. He’s grateful for all the musical genes passed down to him but, hey, his mother loves music and his stepfather had quite a music collection too. His natural father probably passed on his vocal chords but he gave him little else – especially not time – and Jeff thinks he’s got something to give the world himself. He’s right.

Born 27 years ago, Jeff Buckley spent a lonely, insecure childhood and adolescence being dragged from West Coast city to western village and farm by a mother filled with an insatiable wanderlust.

“We’d spend a few months in some places, longer in others. But we never hung around for long. The best places were also the worst because just as I’d make friends with someone we’d be out of there. I got pretty good at working out who wanted to punch me and who would defend me. I’m an excellent judge of character now. I guess my mother just always wanted to know what was around the next corner.”

Eventually he struck out on his own and headed east, arriving in New York in 1991. Initially, he planned to become an actor.

“But there’s always been music. It’s been my friend, my ally, my teacher, my tormentor … I can’t recall a time when it wasn’t there. And singing just took me over. There was a time when I stopped singing, between 16 and 19, but that was done on purpose, maybe as a punishment, maybe as a cure.”

Would Jeff care to elaborate? Eyes narrow, eyebrows lower.

“That’s kind of personal.”

Uh-huh. Jeff Buckley made his first steps on the solo ladder – he’d been in several bands previously – around the New York folk circuit. A live EP, Live at Sin-E, came out of this period but Jeff had already decided that the constraints of a solo performance were too restricting. So he holed himself up in a studio in Woodstock with a four-piece band and producer Andy Wallace and recorded Grace.

The album is everything you hoped for when the first snippets of news about Jeff Buckley started filtering back from New York last year (Tim Buckley’s son with his father’s vocal range and his own tortured musical soul? Noooo). Yes. It’s like someone taking snippets of all the music they know and inventing a new musical language from it.

First, there’s the voice. He shares the amazing vocal dexterity of his father, for sure, but when you listen to him it’s like hearing Liz from the Cocteau Twins for the first time. The words have meaning here, but all the significance is in the tone of his singing. Before you come anywhere near a lyric sheet you understand the emotion behind each line. Longing, pain, lust and hope all bursting out of this little body at once.

Then, there are his songs. Within the simple constraints of guitar, bass, and drums (and some extraordinary string arrangements) he creates a dense but immediate emotional vessel that cannot be pinned down in any rock, soul, or folk category, or as mainstream or alternative. It’s all over the place but it sounds new and it means something.

So although you wonder why he felt like including three cover versions on Grace, particularly Elkie Brooks’s Lilac Wine, you forgive him because of the tingling, tear-stained genius of Last Goodbye, Grace and Lover You Should’ve Come Over. It’s a good record and it really doesn’t sound like Tim Buckley at all. Where’s it all come from?

“The words come from here,” he says touching his top pocket. “From memories, from dreams, from people I’ve known. I’m always writing and reflecting on life. I want to suck it all in.

“The music comes from within and outside. Within is the big mystery of life, we’ve all got it. The outside bits are easier: the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, the Smiths – man, I’d fight for their honour, for the words of Morrissey and the music of Johnny – Edith Piaf, My Bloody Valentine, James Brown, Lush – Mikki was at my gig in London.”

Wasn’t John McEnroe there too?

“He came with Chrissie, yeah.”

That’s Chrissie Hynde. What did you and McEnroe talk about?

“That’s kind of private,” he says, his eyes narrowing and the eyebrows lowering once more. “But we spoke quite deeply about some things he’d been going through, things I understood. I told him he was the Johnny Rotten of tennis, the punk genius. He was why I watched tennis, there was art in what he did.”

He’s not smiling. He’s entirely serious.

The time is 2.15 in the morning. Jeff Buckley has broken his audience. He and his band have been on stage for nearly two-and-a-half hours and The Point has been drained.

At first there was drunken heckling from some good old southern boys, but when Jeff first opened his mouth after a 10-minute introductory guitar noodle everyone shut up. Even his band stare in amazement as he sings. Rapturous applause follows each of the first dozen numbers.

But it’s Saturday night and 90 minutes into the show the original audience start twitching. Only a hardcore remain as the set winds to a finale, along with a pack of drunks in off the street. One guy in a cowboy hat adorned with flashing lights wanders around the perimeter claiming he’s watching the new Hendrix. No, he is! That boy can sing! His friend can’t hear though, he’s fumbling with his grip on balance and eventually slumps to the floor by the door.

Jeff, however, is oblivious to all this. He’s lost somewhere in his first encore, a 20-minute version of Big Star’s Kangaroo. He’s trapped on the first couplet, “When I first saw you/You had on blue jeans,” squeezing everything out of the words “saw”, “you” and “jeans”. As he finally spits it out and half steps back from the mic, he looks sapped of all energy, as if that line was the biggest confession of his life. He looks wiped out.

But something pushes him back and he repeats the line, but this time the emphasis has completely changed and instead of sounding desperate it now sounds filthy, as if he’d just made the most lewd observation ever. And then he’s off again, eyes closed, head waving from side to side, happy to be here, just singing, just letting all the insecurity, all the joy, all the worry come flooding out through his mouth … No tomorrow, no yesterday, just the present …

Suddenly he’s leaping up and down in glee, revelling in one of the most desperate, depressing songs ever, happy to have it coursing through him, bellowing tunefully. Joy, joy, joy! He’s either cursed, or the luckiest man alive.

© Ted Kessler, 1994

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion