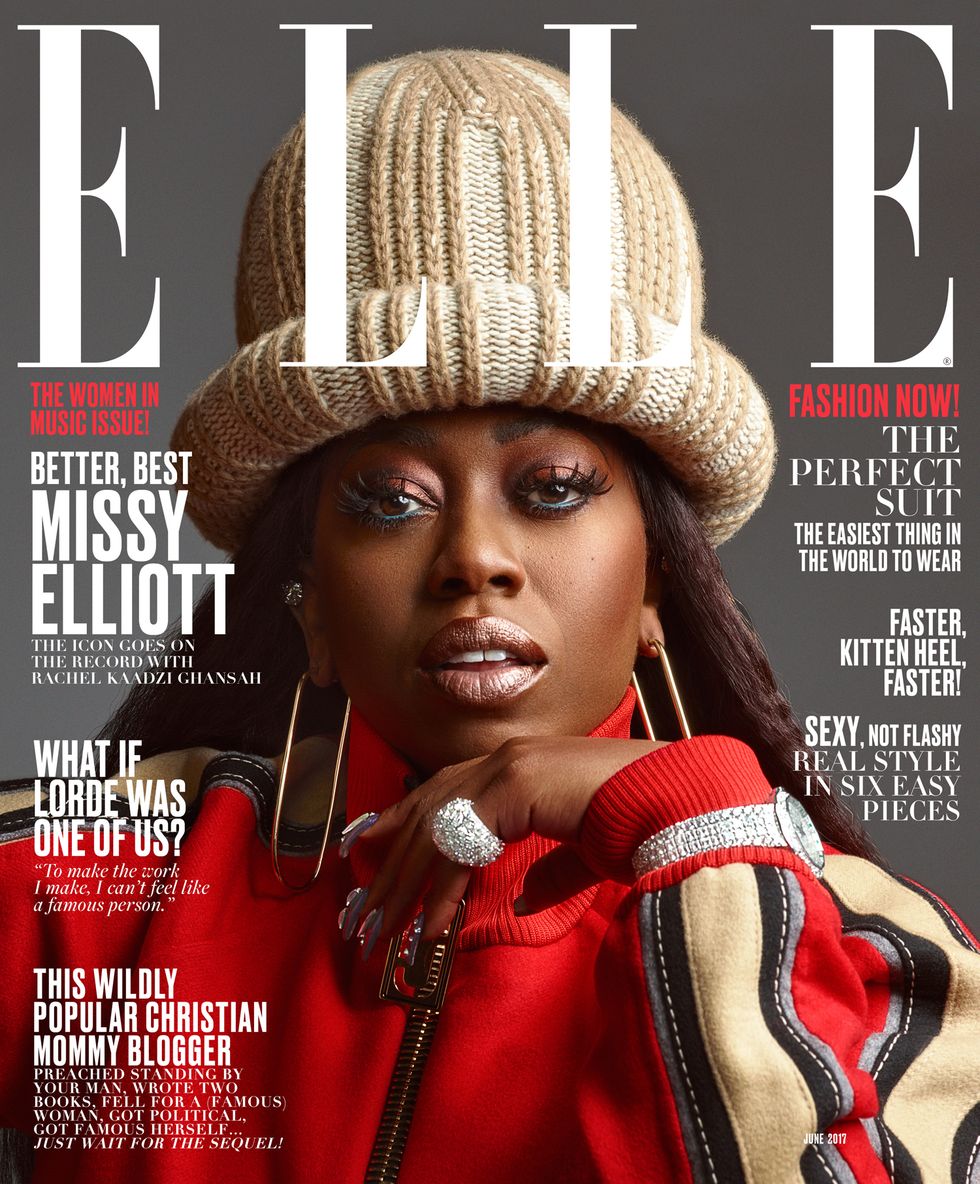

This article appears in the June 2017 issue of ELLE, on newsstands now.

At the photo shoot, the accoutrements of being her precede her. A tray of acrylic nails and an almost-empty bottle of professional-grade nail polish remover are carried by Bernadette Thompson, the Takashi Murakami of manicurists. A tall, strong-looking man walks around distractedly, wheeling a Louis Vuitton duffel bag that is smaller than his forearm; from time to time, he spins it in a wide circle out of boredom. Jewels—gold chokers, hoop earrings, and rings in a velvet-lined box—are attended to by a thin young man wearing a black Balenciaga fitted cap and high-top Nikes. There's a bottle of jewelry cleaner harnessed to his chest and a chain of styling clips attached to his hoodie strings; he looks listless, like he has given his body over to the task. On the table, someone has set down two Kangol hats, one tan, one black: fuzzy, wearable homages to the golden era of hip-hop. They sit there like low-key crowns.

I take a seat out of sight, behind Misa Hylton, the stylist who is the reason people let their pants sag and their Calvins show. Dressed like a ballet dancer from Brixton—or is it Ginza—in a baggy gray sweatshirt and a sheer, tutu-ish white skirt, she sucks on a lollipop, not saying much but taking everything in. When Missy Elliott needs help pulling off her shoe, Misa rushes in to steady her. I recognize the intimacy of it; it's like having your mother or your sister oil your hair. They share a joke; Missy laughs. Misa walks back to her seat, and because they seemed so comfortable, others start to crowd around to look. I still can't see anything from my seat, but I can hear Missy ask something so softly that it has to be repeated and shouted back: "Everybody move back and give her some privacy. Please." Then a large white scrim is stretched out that totally eclipses her from our view. And she turns into a silhouette behind the screen.

What does it mean to be a shy black woman performer in a world where black women are never thought to be shy? Before I went to meet her, I had read articles that decided it just wasn't possible that Missy Elliott is shy. The Guardian wrote that "scary diva is what you expect"; they do not explain why they expected her to be scary, they just say it. In the same way that no one explains what I should expect when I'm told over and over again that Missy Elliott is very shy, without anyone offering a larger understanding of what it might mean. Would she need to be coaxed to open up? Would she not answer my questions? At the shoot, the photographer yells out to her: "Don't be shy—I love it! Let's turn the music up."

Although I got the sense that others were fretful about how this "shyness" would manifest itself in our conversation, after I watched videos of her performing in concert, I was not.

What no one seems to realize is that Missy, like most shy black girls, had long ago been forced to master a certain skill: to hammer down her shyness, along with any fear, to some low, unseen place deep inside of herself, and keep it there until she could step over it, again, again, again.

From the moment I walked on the set, I assumed that Missy Elliott was someone who had this skill, that her ability to rise was ingrained, and I wasn't there for long before we are all watching just that: Missy the Performer—exuberant, high-stepping, arms up in the air, roof-raising, and hair whipping—taking over the monitors and smiling like a woman who has released five platinum albums, possesses four Grammys, and has sold 30 million records and knows very well how to overcome being called scary or feeling shy.

When Missy Elliott dropped her debut album exactly 20 years ago, she altered the spectrum and the range of hip-hop. She made it wild and hyperdimensional. Suddenly, we could all see and hear more. The first rap album I ever purchased was Supa Dupa Fly. And the most important video in the story of my life is "The Rain." On "The Rain," she raps about what still sounds like a perfect day: some light precipitation that clears, smoking some weed, driving to the beach, and dumping an undeserving man. It's a simple enough narrative, but she made it sound strange and wonderful. This was what hip-hop would sound like if it were conceived inside of the calyx of an African violet, unfurling and wet.

I remember seeing that video for the first time in Atlanta at my cousin's one summer in 1997. I was 16. We didn't have cable at our house, so my sister and I stood in his basement and stared at the screen as a woman in a bubble suit that seemed to be filled with equal parts helium and black cool wobbled and bopped. These were lyrics we got intuitively even though we usually didn't understand a word. The vertiginous beats, the cacophony of thunderclaps, and her movements—both fluid and staccato—put me on the floor. I lay there, sweating in that Southern humidity, wondering what I had just seen.

I spent those first early summer weeks in Atlanta fucking up the norms of my cousin's neighborhood, a place where the social codes seemed to be as thick and intricate as in Downton Abbey or any E. M. Forster novel, but with sweet tea and beepers. I was greedy to fit in and also aware I never would. We had been there for two weeks when I saw her, sitting on her "Hill's like Lauryn / Until the rain starts, comin' down, pourin'." Years later, she would put it all into words and boast, "For those of you who hated / You only made us more creative." The double entendres, the hair flipping, the irreverent eye rolls, the smirks, the wink, and the symbolic power of putting on an ink-colored balloon suit and becoming blacker, larger, lovelier, and gigantic with daring weren't lost on me.

Pharrell Williams, who has known and worked with Missy for almost 25 years, calls me on her behalf one Sunday afternoon. He talks about her properly, like she is a sonic theory, a leader, and a woman he adores as a creative liberator. "We came up in a time where we were always told no. Where we were always placed in a box. And she defied it. Over and over again. She defied the physics that were dictated to us. She ignored the gravity of standards and prejudices and stereotypes. She ignored that gravity."

Missy Elliott is in constant metamorphosis, but there is still something about her that feels like your homegirl—if your homegirl had a fleet of cars that include a Rolls-Royce, two Lamborghinis, a Porsche 911, a Ferrari 599, an Aston Martin Vanquish, a Spyker, a Range Rover, an Escalade, and a Jeep Cherokee that she says she prefers over all of them. Missy owns enough houses to start a small village (she splits her time between Florida, Virginia, New Jersey, and Los Angeles), but she tells me that she just feels lucky not to have to pay rent and to be financially secure. These are the rewards of being a 45-year-old humble rapper who is still very much in demand at a time when other rappers her age are trending down.

But what makes her iconic is not the numbers; it is what she empowers in others. Missy was always aware of her worth, her real worth—not the fluff or the proxies for currency and confidence that most people depend on. She always expressed what so many of us feel on the inside but have no model for how to display. Her refusal to discuss her personal life has allowed her to deftly deflect any inquiries about her real life toward her surreal life: The one she inhabits with her many costumes and her various personalities. In almost every video, Missy Elliott is a different character (a black Barbie in "Beep Me 911"; a floss-fluorescent, bald-headed creature in "She's a Bitch"; a black Beatrix Kiddo at war with a rival gang that's driving the Pussy Wagon in "I'm Really Hot"). This is the stuff that makes her Missy Elliott, the legend. It is a demand for privacy, but also a sign of wisdom. She's kept our eyes on the prize. She seemed to know early on that the only thing that matters is the work, and it can look fun. But ultimately, the relentlessness and the far-reachingness of it are what have kept her in orbit.

Missy Elliott is a creator's creator. They say that, before he died, Michael Jackson asked her to teach him how to rap. The Dirty Projectors work below a triptych of the people they consider to be the all-time greats: Joni Mitchell, Missy Elliott, and Beethoven. Tyler, the Creator once told GQ that in his mind, alongside Elizabeth Taylor, Missy Elliott was one of the most stylish women ever to exist. "I'm not even talking about her normal dressing. Just the swag that she had in her videos. She made a fucking plastic bag look awesome," he said. Björk, Herbie Hancock, Debbie Harry, Lil Wayne, and Solange Knowles cite her as an inspiration. And Patti LaBelle has thanked her for bringing R&B back. "Missy's so amazing," Thom Yorke of Radiohead once said, that "she makes me want to spit."

While other rappers were adversarial, making you feel broke, or uncool, or backed up against despair, Missy was inviting us to join her party. Others insulted us for listening, told us about what we didn't have, didn't own, and couldn't brag about, whereas Missy said, Forget who you are, forget what you heard, and come dance with me. In Missy Elliott's songs, bodies jiggle, jangle, they sweat, they drip, they drop, they are invested in the beat. In the early eighties, Michael Jackson gave an interview in which he told the interviewer that above all, he liked "to really forget." What feels good about Missy's music is that for four or six minutes, your body is helmed by her control of the beat; you can "really forget" your own life because there is so much to pay attention to in hers. In the "Pass That Dutch" video, she runs through a primer of black footwork in a cornfield while instructing us to work our legs. In "Lose Control," she samples an old electro song by Cybotron, turning things frenetic, until they sound double-timed and fast enough to fly off the handle. In "Slide," a track that feels enormous, a booming cut-time march, she uses a simple rhyme scheme and her background vocals to remind us to work the waist and keep it slippery. "Slide, slide, dip, shake / Move it all around," she purrs. Missy raps from within the rhythm—she doesn't work against it or with it, she doesn't ride it, she becomes it. Words zigzag and stretch to match time signatures. She can speed them up and slow them down; she organizes her harmonies like string sections; and if she can't do it alone, she'll invite someone else—Ludacris, Jay Z, or Tweet—to join her.

What I realized when Missy and I finally sat down to talk is that Missy is communal and sentimental in a way that hip-hop at times denies itself. She tells me about a last-minute sleepover party that she had with Mary J. Blige, Queen Latifah, Misa Hylton, and Lil' Kim in Virginia for her birthday a few years ago. It touched her that they could be "real friends, not just friends for the camera." She seems far too delicate to be asked about Aaliyah, the singer who died in a plane crash in 2001, who was her best friend, collaborator, and "little sister." Missy mourns and pours visual libation to Aaliyah in most of her videos and many of her songs.

Missy Elliott's work doesn't deny death, or poverty, or bad times, but it pushes for recovery. In her most recent single, "I'm Better (feat. Lamb)," which was released in January, the chorus circles around and gets repeated with a robotic flow: "I'm better, I'm better, I'm better / It's another day, another chance / I wake up, I wanna dance / So as long as I got my friends /...I'm better, I'm better, I'm better." This is not a boast from her to her fans; it is a mantra to them from her, even if there is a self-help quality to it. What matters more is that it feels determined, and that is what her fans depend on her to provide—the good news.

She was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Patricia, a dispatcher for the power company, and Ronnie Elliott, a former Marine. She was their only child, and her parents named her Melissa Arnette Elliott. Missy told me that when the other kids in her class were asked what they wanted to be, they changed their minds every other week. "It would come to me, and I would be like, 'I'm going to be a superstar!' And the whole class would bust out laughing. But every Friday I would say the same thing. And I would watch them change to different things. Now the doctor is going to be a fireman, but still, when it came to me, I wanted to be a superstar. They thought I was the class clown. But I was like, 'I'm going to be a superstar.' So when I would get in my room, it was like, if y'all don't see it, I'm going to create it myself."

The black sculptor Augusta Savage once said of her father that she believed his violence was the result of him trying to whip the "art out of her." The expression of her artistry, her voice being utilized outside of him, was an affront to his masculinity. So he beat her and tried to break her down. Missy's father beat her mother almost every single day. He dislocated her arms; he berated her. He hit Missy only once, but the violence and instability in her life were relentless. She was eight when an older boy, a family member, saw her vulnerability and preyed upon it—he began molesting her in the afternoons.

Unable to stop her father, put off her molester, or save her mother, Missy shut her door. She turned her room into something that she describes as her Wonderland. This was where she would write fan letters to her favorite singers, the Jacksons, with the unexpressed hope that they would appear, see how musically gifted she was, and come to her rescue. The Hype Williams–directed videos that would define her sensibilities decades later were conceived in spirit in this workshop. Here, she practiced singing along to the radio or to the records her family gave her. And before each performance, she twisted her doll babies' arms up, so they were frozen, forever applauding her.

There are two ways to look at a story like Missy Elliott's. The first is within the context of that little girl now. All grown up, in her mid-forties, talking with me while wearing four diamonds in her ears that are bigger than my eyes. This is the woman who will tell you matter-of-factly, "I believe that I spoke it all into existence," and can explain year by year how she actualized her vision, but gives glory to God that she did. The other way to see this enormous dream is as one that was steeped both in pragmatism and what could not be helped: fate.

Although she does not call it this, Missy Elliott believes in the technology of the self, the idea that we can alter our lives by what we create and transmute, and in doing so, we can become invincible. For her, black innovation, black America's ability to overcome all odds and create, are a kind of passed-along technology. "We are survivors, and once we know that, we are unstoppable," she tells me one evening, as the sun makes it look like there are long, Dalí-like threads attached to her sequined sneakers. "I always said I wouldn't be no other color, because if there's one thing about us, we never really had, but we know how to—we know how to survive."

Missy survived abject poverty and years of abuse by tucking herself into sound. She was young, but when she listened to music, she found it impossible to be casual about it. Instead, she immersed herself in the process; she became the song's student. From her father, she learned to listen to the Temptations and Marvin Gaye. "I remember when 'Sexual Healing' came out. It made me listen to a record like that and think of how to do records like 'Pussy don't fail me now,' " she said, quoting her song "Pussycat." "I was trying to find creative ways of doing stuff.… And my mother had the gospel side, where I sat and studied their harmonies."

When she wasn't studying, she practiced. Missy Elliott had no Joe Jackson. She was no man's babe in the woods. She was self-actualized, self-realized, self-taught. There was no father to her style, but she had many mothers and sisters: Queen Latifah, Donna Summer, and Grace Jones. By the time she reached high school, Missy had started cutting class to invite friends over to rehearse in her living room, and her once-high grades plummeted. All of this alarmed her mother, who'd packed up a moving truck after her father had left for work one day; the two were living on their own. Her mother knew Missy was intelligent and just wanted her daughter to do the right thing, not realizing yet that for her daughter, music wasn't a sign of delinquency, but her path toward the only future she could envision for herself.

We were discussing her rocky years in school, during which she was identified by her school district as having both a "genius" IQ and being in extreme danger of failing every subject, when Missy asked me if I had ever heard of Poe.

"You know Poe?" she asked me, with an urgency that caught me off guard. "The Raven?" she added, smiling to conceal her slight impatience.

"Edgar Allan Poe?" I asked.

"Yes, so I studied, locked down—cause I knew I could do it…and when I had to do The Raven, I turned it into a rap, had one of my friends beatbox. I turned it into a rap! Got an A!"

"Are you big poetry person?" I asked her, since hip-hop is black America's repurposing of the poem.

"Uh, well… I wouldn't say that necessarily," she said, laughing. Then she stopped to think, and she got reflective. "You know, maybe I did like it. Because I murked that. I murked that."

It was around then, in high school, when her friend Magoo connected her with Timbaland and Pharrell Williams. Timbaland, she said, "had a little Yamaha keyboard, and Tim's hands are humongous. He was able to take the claps, the little dog sounds, and make beats with it. Then I just started rapping and singing over him playing with the Yamaha. Tim was very quiet. Pharrell was way on planet Mars. And, you know, I was just whatever. I was kind of crazy. But for whatever reason, we all understood each other."

The geography of Virginia—Southern, hanging off the edge of the East Coast—also inadvertently fortified their sound. They had very little access to what was trending, and it set them free to experiment and make music from what they had. "We got everything so late," she recalled, "it also allowed us to be different because we didn't hear. I will never forget when I first met Pharrell, even being from Virginia, he always was so different. I remember him coming into the studio, and he had some jeans on, and he had the cuffs where they came all the way up to his knees! And I had never seen cuffs that big in my life! And I was like, 'What part of Virginia he from?' "

At the time, Pharrell and Timbaland were in a group called Surrounded by Idiots, and Missy had an all-female rap group called Fayze. When Fayze found themselves in contact with the road manager for Jodeci, who at the time were the biggest force in R&B music, Missy devised an elaborate plan to audition for the group in outfits that matched the ones that Jodeci was famous for. Missy had never performed for anyone this famous before, but she knew what people like James Brown and Tina Turner had done. She took that workhorse approach and told the other girls, "I will need y'all to kick a leg up and put that cane on the floor!" It worked: Fayze soon had a record deal and an invitation to join Jodeci at their house in New Jersey.

Alice Walker once asked in her essay "In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens": "How was the creativity of the black woman kept alive, year after year and century after century, when for most of the years black people have been in America, it was a punishable crime for a black person to read or write?" Imagine the discouragement, the slights, and the drudgery that were directed toward these women when they, too, contained art. "Listen to the voices of Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Roberta Flack, and Aretha Franklin, among others, and imagine those voices muzzled for life." Because so many of them couldn't express themselves, "our mothers and grandmothers have, more often than not anonymously, handed on the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see: or like a sealed letter they could not plainly read." When she was little, Missy's mother had been offered a chance to tour the world singing gospel music, but Missy told me that when her mother saw her daughter in the window crying, she put her bags down and walked back in. When Missy walked out the door of her mother's house in 1991 and drove away from Portsmouth, she was doing what her mother could not. She has what Walker described as "the living creativity some of our great-grandmothers knew, even without 'knowing' it." And like those women, but with the dream of performing on bigger stages, Missy Elliott "never had any intention of giving it up."

When Katy Perry asked her to appear for exactly 2.5 minutes in the middle of Perry's set at the 2015 Super Bowl, it was Missy's first big appearance in years. Missy hadn't released an album since 2006. She's said that backstage, having had a panic attack that required medical care the night before, she swore to herself, "If I can get over this [first] step, then I know all my dance steps will be on point." Twenty-four hours later, "Get Ur Freak On," "Work It," and "Lose Control" would be downloaded about 20,000 times each, taking turns hitting the number one spot for downloads on iTunes.

Missy Elliott's mind thinks in bloom, and ideas emerge like buds pushing up from the ground. The Super Bowl story prompts her to tell me that typically she would be most comfortable having this conversation sitting on the floor.

To stay grounded?

"Yes, to stay humble."

Or maybe to remember that this adulation was not always there. The first big song she wrote was for Raven-Symoné in 1993, but when it came time to shoot the video for "That's What Little Girls Are Made Of," for which she rapped a verse, she didn't even receive a call about it. In the video, a thin, light-skinned model who has swallowed Missy's voice raps along with Raven. The rejection was so painful that Missy gave up on trying to be a star and devoted herself to songwriting. Three years later, she and Timbaland would write and produce the majority of Aaliyah's classic album One in a Million. When the record labels circled back around, this time they understood: They were signing someone who wanted her own imprint, with complete creative control over her music and the ability to freely write and produce for others. Missy Elliott was 24 when she got what she wanted from Sylvia Rhone, the CEO of Elektra Entertainment Group at the time, and she called it her new record label Goldmind Inc.

There is an early New Yorker profile of Missy that once referred to her look in "The Rain" as being that of a "cyber mammy." But Missy has never served or played servant to anyone in her life. There is nothing about Missy now, or then, that could belong in anything but a prosperous, liberated future. She even sings in "Work It": "Picture blacks saying yes sir, master? No!" A mammy as a trope was never a self-defined, self-articulating, sexualized woman. We knew nothing of her pleasure. If anything, the trash-bag suit in "The Rain" was about taking it all with you—the rarely spoken-about black woman's pleasure principle. (And who has written more songs about being sexually satisfied and self-satisfying than Missy Elliott?) The knowledge that you are beautiful. It is having been denied, and returning tender, exuberant, monumental, and hyperdimensional. "To me," Missy explained a few days after our first conversation, "the outfit was a way to mask my shyness behind all the chaos of the look. Although I am shy, I was never afraid to be a provocative woman. The outfit was a symbol of power. I loved the idea of feeling like a hip-hop Michelin woman. I knew I could have on a blow-up suit and still have people talking. It was bold and different. I've always seen myself as an innovator and a creative unlike any other."

What is off-putting about some of the interpretations of Missy Elliott's style is that they apply a retrograde framework to a woman who is so firmly from the future. And in doing so, they put undue, incorrect emphasis on her body, and assume things that tell us nothing about her and everything about the erasures that occur to women like her. In the late 2000s, she began to feel ill and suffer dizzy spells and unexplained weight loss. This played a large part in her taking time off. She was diagnosed with the thyroid condition Graves' disease, but when she did an interview with a New York radio station and tried to explain her condition, the host described her weight loss as the upside of her getting sick. To be a woman is to know that your flesh can matter more than your brilliance.

All world-building is an act of construction that requires real effort and no shortcuts. Perhaps because producing necessitates a specialized understanding of music, Missy the Producer doesn't get as much play as Missy the Performer. Both are solidifying elements of her autonomy, but the former guarantees her ability to be the architect of her own sound. Because it's a science to produce—it's a kind of alchemy to sit in a studio and bring forth music from nothing—women are discouraged from doing it. They are ignored when they master it, and, like any other science, they are underrepresented among those who are thought to be the best at it.

There is an interview that Björk did years ago for French television in which she describes the stress of being a woman and containing a certain rare level of musicality. "When somebody comes to make great music, I feel like I have less work to do," she confessed. "When Missy Elliott or, like, Peaches arrives with something good, I would be like, yes! It means I can do other things. Maybe I don't have to worry or stress about rhythmic music anymore because they are taking care of that." Young women are regularly taught how our bodies can be of service or put to work toward the desires of others, but rarely are we instructed how to be in charge of our art. "I remember," Björk has said, "seeing a photo of Missy Elliott at the mixing desk in the studio and being like, aha!" That Missy can draw all of the music out of herself, and work the board, write the music, and execute her ideas often goes undiscussed, but it makes her an aberration and a lighthouse. "When I was a kid, I wrote raps and I wanted to sound just like Missy," Syd, the lead singer of the R&B group the Internet, texts me one morning. A Grammy-nominated polymath, Syd sings, writes, produces, and engineers the majority of her music (and for years did so for her band, Odd Future). And like so many young black women in music, she knows she is a direct descendant of Missy Elliott's quiet revolution in the studio. "But I was even more inspired by her when I got older and learned how much other music she had written and produced. She is definitely one of my biggest role models in music. She's a genius…and her attitude shines through."

Missy Elliott has written more than 500 songs, produced music for Ciara, Janet Jackson, Mariah Carey, and Whitney Houston, and taken just three vacations in her entire lifetime. She has written gospel songs that seem ready to break all the stained glass in the chapel with their high notes and full harmonies, and she has written a song where she implores her "pussycat" not to fail her. In her "Sock It 2 Me" video, she became the black woman who promised a new generation, just like Uhura did in Star Trek, that not only would we survive the new millennium and be found in the farthest reaches of the galaxy, we would be there fighting aliens in Teflon spacesuits, cracking up with our girls, smacking our gum, and looking good while doing it.

In her videos, Missy Elliott taught us how to move to her sound, to bop, to bounce along with her. "Missy was making films, you know? She was making three-minute films, working with the best technology at the time, and she still does, by the way," Pharrell explains. "And it felt like there were no bounds to what she could do, and she continued to teach people over and over again, you can do this, you can do that." And we learned to enjoy watching her. "I know my dances are going to be the puzzle," she says, "so even if you thought it was weird, I put the visual in your face so now you see how you're supposed to move to it." What she did with her body is move it as a dancer and performer. And her moves seem natural, like you could try it and not make a fool of yourself. But really she is possessed of a very singular ability as a choreographer: She knows how to put us all on the moon to dance with her without self-concern or a care in the world, and that is what only the greatest pop artists have done.

What is disarming about her in person is that all of these parts fit and feel rooted. She is a businesswoman, a flashy rapper, but she has a songwriter's need for solitude that brings to mind the moods of Kate Bush, Laura Lee, Sade, and Laura Nyro. The need to retreat and go deep and remain exceedingly private. "I'm probably like the lamest but still sauciest artist out there," Missy says. "I don't know how that works, where you cannot do nothing and still be saucy, but my friends, they always tell me when they come to the house, 'Ohh, you don't need to be an introvert' and 'Dude, you gotta get out, like you don't do nothing but just sit in the studio.' But you know, for me, I find comfort in that for whatever reason. It's, like, therapeutic for me."

Until it flooded, Missy spent a great deal of time at her mountain house near the Poconos, where bears would wander into her front yard and, because she was alone, she would have to wait until they wandered off to go outside. She tells me she likes to drive her cars and listen to old soul music.

She has worked with Timbaland since she was a teenager, but even he has never been in the studio with her when she records. "I'm private about recording, because it allows me to be myself and not have to worry. The energy has to be right for me, if I'm in that booth and somebody's energy is off and not really, like, moving their head or something, it may make me start to doubt what I'm doing. You gotta be careful in the energies that you let come in the room, because it will begin to make you doubt and fear and not want to take that risk."

"We been quiet too long lady-like very patient," she says in an interlude on her 2002 album, Under Construction. And there is a moment in her VH1 Behind the Music special where Missy's mother cringes. She is discussing Missy's decision to reveal the sexual abuse and violence that barbed itself around her childhood. "When Missy went open about the abuse," her mother says, "I was like, This is our secret; you don't tell the world what happened." Her mother was not being malicious. She was just afraid for her daughter. For many years, her mother lived with her in her house in Virginia; they are very close. But this is a generational reminder, a well-worn mode of discretion that most black girls hear at some point in their lives. It comes in many forms, a whisper in your ear to always keep your panties clean so if you are killed in an accident they will know you aren't a dirty woman, a curt warning not to tell your business in the street—these silences, this keeping it quiet, are supposed to let the world know who we are. I realized that what Missy had done on a very basic level is decide that those good intentions—meant to beckon us toward being flatter than we are, quieter than we are—wouldn't work for her as a rapper or a songwriter.

In 1983, Octavia E. Butler, the first major black woman science fiction writer, published a story, "Speech Sounds," that imagines a world where almost everyone has lost their voice, and because of that they no longer remember how language works. One of the few exceptions is a woman named Rye, and as the story progresses, she comes to realize that even though is it dangerous to speak, she has to, and she has to help the children who have been left behind, who like her are still trying to form words and express themselves under such perilous conditions.

On Missy's 2015 song "WTF (Where They From)," there is a sample of a young girl speaking. The voice belongs to Rachel Jeantel, the friend of Trayvon Martin who was on the phone with him when he was murdered. Missy doesn't bring this up, I do. She goes almost mute when I say that by sampling Jeantel's voice, Pharrell and she have done a remarkable thing that has reversed what usually happens to the words of girls who look like Rachel Jeantel. They have preserved them for the record, credited her for her voice and her words, and made sure she got paid. The witness becomes the writer. From the test comes the testimony.

And so a shy girl rises to the occasion, to speak, to write, and she becomes herself—because who else is going to explain why it is imperative that women don't put up with lousy lovers, or show us that we can wear sneaks every single day and still desire to get those nails done every other day? (Her nail tech, Bernadette, tells me: When it comes to glam, Missy is the most feminine artist of all time.) Missy is a multiplatinum artist who views Andre 3000 and Erykah Badu as her creative peers; she is an icon who likes to sit on the floor. This is what she does best: convince others that all of this is contained inside of her, while still finding a way to remain herself.

Across the street from the photo studio, the Chelsea Piers are turning themselves over to the night. And Missy's publicist and team are in a hurry to make sure I'm not taking up too much of her time, but Missy herself doesn't seem rushed to go anywhere yet. If anything, she seems deliberate. She sips through a straw from a cup of fresh-squeezed juice, and then she holds the cup with both hands. Her baseball cap is cocked to the side, and her two-inch nails are painted iridescent blue. Her legs are open but locked at the ankle. She looks in command—even more so because she is smiling.

I want to know more about her absences from the spotlight. What is it like to re-enter a world where Twitter can determine who becomes president, where music can feel like it was created to last for exactly for one minute and then disappear into the ether?

Yeah, it is a brave new world, she agrees. But she isn't despondent. Not at all.

"One thing I won't do is compromise." She takes another sip of juice and thinks for a moment. "I will never do something based on what everybody else is telling me to do. And have to kick myself in the ass every night," she says, drawing her head back and shaking it.

"Nah. I have to make sure that it's right," she continues. "I've been through so many stumbling blocks to build a legacy, so I wouldn't want to do something just to fit in. Because I never fit in. So…."

I wait for her to finish her sentence, but she doesn't. Her smile just grows into a laugh, a shy one, and then she shrugs. As if to say, Take it or leave it, love me or leave me.

It's a blueswoman's confidence, the realest shrug in the world, a gesture that comes from knowing full well that most of us made our choice about her a long time ago.

Have thoughts on this story? Email elleletters@hearst.com.