I remember reading Barbara Jane Reyes’s Poeta en San Francisco years ago and being struck by how under the skin real her use of language was. Poeta en San Francisco won the James Laughlin award of the Academy of American Poets.

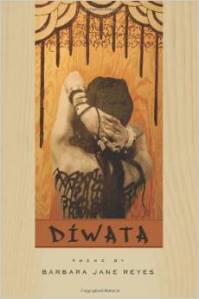

Born in Manila, Philippines and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area Reyes’s work is suffused with a consciousness of the worlds and cultures that she lives in. Diwata, which is her third poetry book, is a hybrid work. It’s a very interstitial work and in my opinion this book transcends genre as it plays in the worlds of myth, magic and the real. As in Poeta, Reyes’s use of language evokes a body response. That keen and critical eye, a strong social consciousness and the wisdom of knowing are also present here.

At present, Barbara Jane Reyes is an adjunct professor at University of San Francisco’s Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program where she teaches Filipino/a Literature in Diaspora, and Filipina Lives and Voices in Literature. She has also taught Filipino American Literature at San Francisco State University, and graduate poetry workshop at Mills College, and currently serves on the board of Philippine American Writers and Artists (PAWA).

Considering your work as a poet, as a writer, as an academic what have been some of the major challenges/obstacles that you’ve encountered and how have you dealt with/overcome them?

I don’t consider myself an “academic,” though I am an educator. I am an adjunct professor between three different institutions, and I have a full time job outside of education, literature, and the arts. So that would be the first and major challenge – finding the balance, and the ability to multi-task. Keeping the house clean is a challenge, given my long work days. But I persevere, and my husband is my greatest supporter.

As a poet and writer, major challenges for me have come from various sectors of the Filipino American community. I have been told that the content of my poetry is painful and upsetting; I have also been told that it is also angry, aggressive, and abundant in ugliness and profanity. People want to distance themselves from what is painful and upsetting, and what is considered socially problematic.

I have been told that Filipino Americans want to see themselves represented positively, and that they want only what is “beautiful” about ourselves to be seen by others. But what is “positive” in our community? Who determines that? And what happens to those whose life experiences are not deemed “positive” by those given standards? Similarly, what is “beautiful,” must be interrogated; what are our standards of beauty, and where do those standards come from, historically?

I am troubled by omissions that result from only “positive” and “beautiful” portrayals. There is plenty to be angry about, and real life is ugly. It is important for me that my work embraces these realities.

Related to the above, as a “cultural critic” (a term I have consciously placed in scare quotes), I have been told that my criticism and commentary also upsets people within our community, that it is “reckless,” “destructive,” and “dangerous,” because it upsets the sensibilities of others. This tells me more about what people in the community fear, versus what is “wrong” with me.

I have been told my mannerisms are aggressive, but I also have to ask what the gender expectation is, why it’s being imposed upon me, and by whom.

And so, in response to your question about how I deal with or overcome these challenges, I think the most honest thing I can say is that I allow myself to process, and then I move on and continue to work. This all allows me to grow and to refine my

say is that I allow myself to process, and then I move on and continue to work. This all allows me to grow and to refine my

ideas of who comprise my community. Diane di Prima recently said that it’s not difficult to find and build communities of like-minded people, and so I do that, and I get to work.

You’ve already written several books of poetry and you continue to produce thoughtful and challenging work. What has the process been like for you? How do you approach a new work and what’s it like when you are producing a new work?

I feel like each subsequent book picks up where the previous one ended. There may be a particular voice, a persona, a phenomenon – a mermaid, a monster, the internet – that in its complexity, continue to fascinate or trouble me, and I need to continue engaging, or digging deeper into it, exploring layers and reflecting upon contradictions.

Sometimes the thing I need to explore more deeply is a concern of poetics – use the page, the poetic line, or engagement with language itself. In general, the process for me is ongoing experimentation with when and how to tighten the grip on any and all of the above, and when and how to loosen it.

On your blog, you talk about performing Filipino-ness. This is something I found very interesting and thought-provoking as in the field of writing/art we face unspoken expectations. I loved your thoughtful post on it and I wanted to ask you about the pressures that you experience as a poet, a writer and an academic. How do you deal with these pressures? (Also considering the communities that you are identified with.)

I think it’s ironic that we spend a lot of time rejecting others’ oversimplified ideas about us as Filipino/as, but then we impose a uniformity of heteronormative, male dominant Filipino-ness upon our own. Many times, it feels there is little to no tolerance for difference of any kind among our ranks. I am most interested in complexity and contradiction, and asking questions – so those things continue to inform my poem-making, as they inform my teaching.

I deal with those pressures by disengaging and redirecting, by continuing to write how and what I want to write, and as I’ve already said, grow and refine my ideas of who comprise my community, people with whom I can work and build. I work, I teach, I write, I edit, I publish. I don’t have time to quarrel with people or try to change them.

One of the things that speaks to me about your work is the way in which you use language. The interweaving of the various languages that we use back home with English–I remember reading Poeta and feeling that jolt of recognition. I am fascinated by the way language shapes our reading experience as well as how it draws us closer or distances us from a work. I wanted to know if there’s a difference when you write only in English as compared to when you write also weaving in the languages that are part of our history. How does this influence/affect your work? And what kind of response do you hope to evoke from the reader?

I actually don’t think I make a distinction, mentally at least, when writing in “straight” English, versus in multiple languages. My experience, coming from a multilingual family (Tagalog and Ilocano), marrying into a multilingual family (Spanish), growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, being educated in the San Francisco Bay Area, living and working in the San Francisco Bay Area,

especially in the urban areas – all of these things inform my use of languages, as much as my time in English Literature classrooms. Of course, I know that we use certain languages in certain places, but as an everyday occurrence, we hear multiple languages — not just Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Tagalog, et al, but also different urban vernaculars — being spoken in various densely populated public places.

Also, my “day job” is in a public health setting in Oakland Chinatown; in my work and in this specific part of Oakland, at least eight different Asian languages are in spoken and written operation all the time. I engage in regular conversations with my colleagues about translation and implication. Because I am in public health, I am also constantly translating legalese, finding ways to unpack and allow others access into this deliberately inaccessible language. That’s much more challenging that code switching in poetry.

So then, writing in this part of the world, or this part of the country, or this specific part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it would be dishonest, or an act of denial, not to write in multiple languages.

What do I hope for from the reader? I don’t know that I can hope for anything, except a realization that monolingualism simply isn’t the norm.

Recently, there’s been a lot of conversation around representation and diversity in literature and media. What do you hope to see as a result of these conversations? As VP for PAWA, what do you think is the biggest challenge that faces Filipino writers in the US?

As above with monlingualism, monoculturalism is also not the norm. And so therefore, our cultural productions would do best to reflect this reality. Media can have as many conversations as they want to have about diversity. As part of PAWA leadership, all I want to do is enlarge the space in which Filipinos write, and to encourage bravery in getting our work out there, in print and otherwise.

I think the biggest challenge Filipino writers in America have would be that we do not collectively know enough about what authorship entails, and that we do not know enough about the publishing industry, when we are trying to represent, to increase awareness, to empower ourselves through the word. Lots of folks in our community believe they have a book in them, and I agree. But the question of how to get that book into the world – how to edit, how to revise, how to build a manuscript, how to determine what publishing houses would be most appropriate for our work, how to query editors and build relationships with them, what exactly publishers do, what distributors do – as a community, if we are invested in more Filipino Americans publishing, we could be engaging in these conversations a lot more, and in some substantial detail.

I think the biggest challenge Filipino writers in America have would be that we do not collectively know enough about what authorship entails, and that we do not know enough about the publishing industry, when we are trying to represent, to increase awareness, to empower ourselves through the word. Lots of folks in our community believe they have a book in them, and I agree. But the question of how to get that book into the world – how to edit, how to revise, how to build a manuscript, how to determine what publishing houses would be most appropriate for our work, how to query editors and build relationships with them, what exactly publishers do, what distributors do – as a community, if we are invested in more Filipino Americans publishing, we could be engaging in these conversations a lot more, and in some substantial detail.

I think of the kinds of relationships Carlos Bulosan formed with editors and publishers – these things are documented not just in his essays and letters in On Becoming Filipino, but also in the widely read America is in the Heart. Let’s not gloss over Bulosan’s professionalism and hustle! Let’s not omit that from our discussions of Bulosan. Let’s learn from it.

Earlier, you talked about how your work has been criticized as being angry and aggressive and contrary to the Filipinos desire to see a positive depiction of self. What I like about your work is that it resists that impulse to only show what’s beautiful. It’s also interesting to me that you grew up in the US and yet your work resists Americanization. Is there a particular moment when you made that decision to exercise this resistance in your work? Who are the authors who you would consider as being influential on the you and the work that you produce today?

Rather than “resisting Americanization,” I think of my writing as examining (Interrogating? Excavating?) Americanization, and this came for me when I was educated critically on Americanization, and when I read other American women writers of color also apparently resisting or examining or interrogating Americanization and Anglo male privilege – Gloria Anzaldúa, Leslie Marmon Silko, Jessica Hagedorn, Audre Lorde, Harryette Mullen, Frances Chung, Haunani-Kay Trask, for example. My American upbringing would not have been the same as those who represented the majority and the mainstream, and so finding these women of color authors writing that complexity, ambivalence, with some degree of grit or edginess or militancy, was a big deal for me.

These days, expanding on America (USA) and América (Latin America), in addition to Anzaldúa, I think of Adrian Castro, Alejandro Murguía, Jimmy Santiago Baca, Juan Felipe Herrera, Jack Agüeros, and especially the mighty Eduardo Galeano, on language, on place, on history. In fact, it’s been fantastic and revelatory being included over the past decade, in a number of Latino poetics projects.

There’s the jazz of Bob Kaufman and Nate Mackey. Of his performances, Mackey once told me that when collaborating with musicians, word starts to approximate sound, and sound to approximate word. There’s the pidgin of Lee A. Tonouchi (check out his book, Living Pidgin, from Tinfish Press), and the fact that he wrote his entire masters thesis in pidgin. All of this really gets me thinking more about how I use language, why I use the languages that I use.

But it’s not just writers of color. I am always happy to revisit Allen Ginsberg, Diane di Prima, Anne Waldman, and to think about not just rebellion and resistance, but also appropriation, borrowing, thievery, whatever you want to call it.

You talk about how we as a collective don’t know enough about what authorship entails. I know that PAWA strives to function as a sort of space where Filipino & Filipino-American writers can share, but is there more we can do to heighten visibility and awareness of the work that Filipinos and Filipino-American writers are doing?

PAWA strives to function as a space not only for Filipinos and Filipino Americans to “share,” but also to have critical discussions about art and art production. We have held events in which Filipino American writers and writers of color “share,” meaning, read from their work, and also speak on the work, its production, strategies and challenges in writing and publishing. They have been able to talk about furthering their education as writers, navigating writing programs, their decision making processes in applying to MFA programs and/or community based workshops such as VONA, Kundiman, Kearny Street Workshop, and/or various writer residencies. We have used PAWA space to discuss submitting our work for publication – how to figure out what are appropriate venues for our work, how to connect with these venues, and whether creating new venues for our work is warranted.

When I was a young, aspiring and then emerging writer, there were really three Filipino American authors who were forthcoming, concrete, and specific with me about publishing industry matters — Nick Carbó, Jaime Jacinto, and Eileen Tabios. Without them, I would not have been able to “figure out” how to get my work “out there,” in which I could critically think about and define what “out there” meant for me. And then strategize how to act upon that definition. So then, mentorship is important.

Other things: In Filipino and Filipino American media, in various “ethnic” media, who is reviewing our books? Authors are reviewing other authors’ books. Can’t this base of book reviewers be grown/expanded?

As far as the larger Filipino and Filipino American communities, education is a big thing. Here, I mean, let’s look at what activism our community is engaged in, to diversify curricula in our school systems.

Last year, I had two students – one Asian American from Hawaii, and one Filipino American from somewhere in Central California – and they told me they had read work by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard and Pati Navalta Poblete in their high school English classrooms. I was floored, because I never read Filipino or Filipino American authors until I was in college, taking Asian American Studies courses. It just makes sense, given our country’s demographics, to have our literature included in American Literature courses.

Another thing: who is teaching our literature? I am constantly astonished that the young Filipino American students who have come to my books have done so via non-Filipino teachers. So, I am glad that non-Filipino educators find educational value in my work, but I am also disappointed when I hear other Filipino American educators say that they do not know how to teach our work. Or that they just don’t teach our work.

So that’s one thing I am thinking about – for young Filipinos to think of Filipino Americans writing books in this country as a normal thing and not a unicorn, our literature has to be able to reach them, in classrooms, in their school libraries and public libraries, in the larger community. Love for reading, and the importance of books have to be cultivated.

Historically, we have had a tenuous relationship with various institutions, and I can’t even tell you how to “fix” this, except that it must be something we all commit to working at as a community. Education and publishing are institutions that are important for us to talk about, and that’s why I mentioned Carlos Bulosan.

I find myself very intrigued also by the interstitial nature of your work. Diwata for instance defies classification. There’s an interesting movement too within the work between myth and the real, between story and poem. Could you share some of the process that went into the writing of Diwata and the choices you made when writing it?

I was reading Eduardo Galeano, who is not a poet. He tends to write in manageable-sized blocks of prose, and his work spans vast history, as well as myth/folklore, and the lives of everyday people and not just explorers and kings. That’s a lot of how I arrived at Diwata’s form right there. Regarding theme, I was already writing about mermaids, and in various personae that I had made up. I tend to write in persona to get away from writing my own POV, which I think is not terribly interesting. But to create, to flesh out these other voices – that’s a challenge for me. I turn to the mythical when I just need to make things up; really, what is real is contentious to begin with. There is Master Narrative, written by conquerors and victors, and rather than completely disregard these, I have to think about how to read these critically. Where, for example, do we read firsthand account of the slaying of Ferdinand Magellan by Lapu-Lapu, but through the chronicles of Antonio Pigafetta?

Still, buried by Master Narrative would be the conflicting, quarreling narratives and testimonies of everyone else, determined by place in relation to the event, interpretation, speculation, belief system, et al. Regarding myth – people turn to myth to explain so much of what they do not understand about the world, so my moving into the mythic in my own narratives shouldn’t be such a surprising and difficult thing to grasp. Regarding story versus poem – mnemonic devices such as rhyme, meter, and repetition which exist in poetry, exist in oral tradition. Poetic verse, and call and response, are parts of many ceremonies and rituals; I think about this on the rare occasion that I go to church, or find myself in a Semana Santa procession, a novena, or a rosary recital.

A friend of mine once told me that when we are channeling work like that, we are standing in an open door between two worlds. Standing and navigating between these two worlds can be wearing at times. Are there things you do to keep yourself from burning out?

That’s some of what I wrote in Diwata, the storyteller as the bridge between worlds. This makes her “special,” in her community, but this also makes her tough to understand. Think of the Tandang Sora character in Ninotchka Rosca’s “Sugar & Salt.” She carries and shares this wisdom, and, without her, the community could really forget themselves, what they’ve gone through, and where they’ve come from.

But yes, it is wearing. In terms of not burning out, I allow myself time and energy to put down the pen, and to view and engage other cultural productions and media — books, TV, film, music, visual arts. I allow myself to do things like go to baseball games, go shopping with my mother. Just have a life.

It’s important that I tend to my life outside the literary and art worlds, even though everything I do (I would like to think) informs my writing and world building. It’s important to be well-rounded, and grown up, no? To pay attention to all aspects of our lives, our families, our health.

I hike and kayak, get myself dirty and exhausted in the natural world, and this actually helps me a lot with my poetics — specifics of terrain and climate, breath, poetic lines, and music happen in measured and deliberate ways. Language I would have otherwise overlooked comes to me this way as well.

There are so many narratives about creative people self-destructing, and I don’t in any way want to forward these. Yes, we are consumed with our work, and yes, we do make the time to see and read keenly, but we can’t neglect our homes, families, health, well-being in the process. Who will take care of us if not for ourselves? The world does not owe us anything. It’s actually grounding for me, in a very welcome way, to think about mortgage payments, groceries, vacuum cleaners, dentist appointments. If I want my work to exist in the real world, I too need to exist in the real world.

A writer is always at work. Now that Diwata is out there in the world, what’s up next? Would you like to share a little bit about it?

Well, since the release of Diwata in 2010, I also had a chapbook, For the City That Nearly Broke Me, published in 2012 by Aztlan Libre Press in San Antonio. That’s with the Indigenous Series on a Chicano/Latino press, and so this has given me a lot to think about, in terms of who reads my work, and/or where my work is received. The poems in that chapbook are centered around city — specifically Oakland, where I have made my home for the past decade, and Manila, where I was born. Again, this ongoing writing about home and belonging.

I also have a manuscript, To Love as Aswang, that’s currently being read by a publisher. That aswang is a creature/character that continues to fascinate many of us Filipina American feminist writers. Pinays cast as monsters. Pinays casting ourselves as monsters. Pinays being monstrous. Pinays as monstrosities.

Actually, the manuscript’s recurring theme is Pinay voice speaking on Pinay body, commodified, objectified, resisting, fighting for self-determination, obtaining agency. All of this is happening as I deal with my relationship with the poetic line.

Do you have any advice that you would give to young writers (particularly to writers from marginalized groups) to help them in the journey that they are on?

Find mentors who will challenge you, who will ask you hard questions, and who will give you honest criticism. Be brave, grit your teeth, and do the hard work.

Keep reading, especially outside of your comfort zones. Keep finding ways to further your own education, whether via graduate school, community workshops, artist residencies, writers’ conferences, writing groups. Become adept at fielding and filtering criticism that is helpful to your projects — learn to become very clear, focused, and articulate about what your projects are and why they are necessary — and do not let others’ ignorance, racism, misogyny, hate, and privilege deter you. That is to say, develop a thick, thick skin, but still maintain your sensitivities for what is most important for you to write, and why.

Stay focused on your work, on making it the best and tightest work possible, and do not waste your energy fighting with people who do not want to understand your work or support you in bettering your work. Keep your day job. Don’t get too comfortable.

Where to find Barbara Jane Reyes:

Website: http://www.barbarajanereyes.com/

Twitter: @bjanepr

Facebook: Barbara Jane Reyes

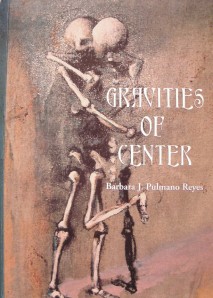

**Clicking on the images will lead you to links where you can purchase a copy of the book. Amazon also carries Barbara Jane Reyes’s books.

Pingback: Ephemera, and the magic and mysticism of the artist and her muse – Barbara Jane Reyes