Why Teaching Poetry Is So Important

The oft-neglected literary form can help students learn in ways that prose can't.

16 years after enjoying a high school literary education rich in poetry, I am a literature teacher who barely teaches it. So far this year, my 12th grade literature students have read nearly 200,000 words for my class. Poems have accounted for no more than 100.

This is a shame—not just because poetry is important to teach, but also because poetry is important for the teaching of writing and reading.

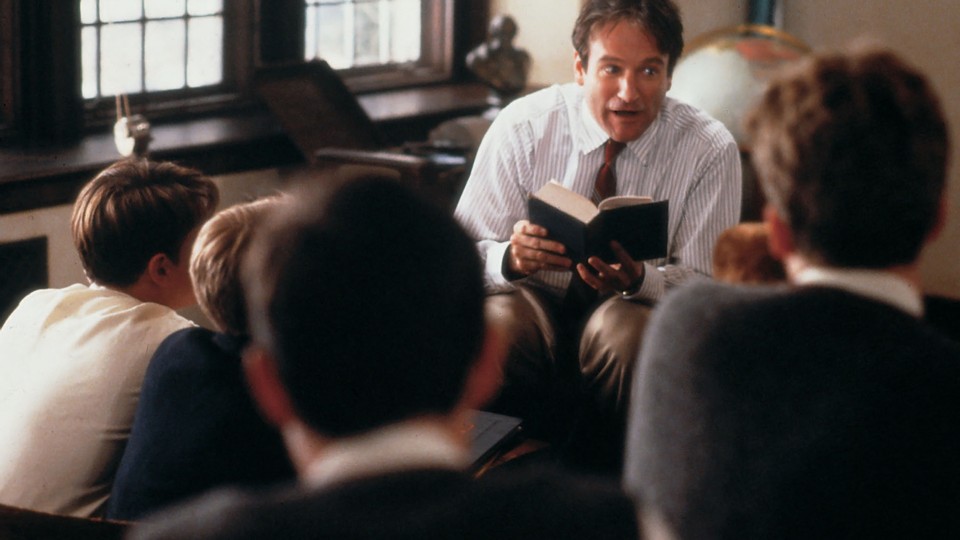

High school poetry suffers from an image problem. Think of Dead Poet’s Society's scenes of red-cheeked lads standing on desks and reciting verse, or of dowdy Dickinson imitators mooning on park benches, filling up journals with noxious chapbook fodder. There’s also the tired lessons about iambic pentameter and teachers wringing interpretations from cryptic stanzas, their students bewildered and chuckling. Reading poetry is impractical, even frivolous. High school poets are antisocial and effete.

I have always rejected these clichéd mischaracterizations born of ignorance, bad movies, and uninspired teaching. Yet I haven’t been stirred to fill my lessons with Pound and Eliot as my 11th grade teacher did. I loved poetry in high school. I wrote it. I read it. Today, I slip scripture into an analysis of The Day of the Locust. A Nikki Giovanni piece appears in The Bluest Eye unit. Poetry has become an afterthought, a supplement, not something to study on its own.

In an education landscape that dramatically deemphasizes creative expression in favor of expository writing and prioritizes the analysis of non-literary texts, high school literature teachers have to negotiate between their preferences and the way the wind is blowing. That sometimes means sacrifice, and poetry is often the first head to roll.

Yet poetry enables teachers to teach their students how to write, read, and understand any text. Poetry can give students a healthy outlet for surging emotions. Reading original poetry aloud in class can foster trust and empathy in the classroom community, while also emphasizing speaking and listening skills that are often neglected in high school literature classes.

Students who don’t like writing essays may like poetry, with its dearth of fixed rules and its kinship with rap. For these students, poetry can become a gateway to other forms of writing. It can help teach skills that come in handy with other kinds of writing—like precise, economical diction, for example. When Carl Sandburg writes, “The fog comes/on little cat feet,” in just six words, he endows a natural phenomenon with character, a pace, and a spirit. All forms of writing benefits from the powerful and concise phrases found in poems.

I have used cut-up poetry (a variation on the sort “popularized” by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin) to teach 9th grade students, most of whom learned English as a second language, about grammar and literary devices. They made collages after slicing up dozens of “sources,” identifying the adjectives and adverbs, utilizing parallel structure, alliteration, assonance, and other figures of speech. Short poems make a complete textual analysis more manageable for English language learners. When teaching students to read and evaluate every single word of a text, it makes sense to demonstrate the practice with a brief poem—like Gwendolyn Brooks’s “We Real Cool.”

Students can learn how to utilize grammar in their own writing by studying how poets do—and do not—abide by traditional writing rules in their work. Poetry can teach writing and grammar conventions by showing what happens when poets strip them away or pervert them for effect. Dickinson often capitalizes common nouns and uses dashes instead of commas to note sudden shifts in focus. Agee uses colons to create dramatic, speech-like pauses. Cummings of course rebels completely. He usually eschews capitalization in his proto-text message poetry, wrapping frequent asides in parentheses and leaving last lines dangling on their pages, period-less. In “next to of course god america i,” Cummings strings together, in the first 13 lines, a cavalcade of jingoistic catch-phrases a politician might utter, and the lack of punctuation slowing down and organizing the assault accentuates their unintelligibility and banality and heightens the satire. The abuse of conventions helps make the point. In class, it can help a teacher explain the exhausting effect of run-on sentences—or illustrate how clichés weaken an argument.

Yet, despite all of the benefits poetry brings to the classroom, I have been hesitant to use poems as a mere tool for teaching grammar conventions. Even the in-class disembowelment of a poem’s meaning can diminish the personal, even transcendent, experience of reading a poem. Billy Collins characterizes the latter as a “deadening” act that obscures the poem beneath the puffed-up importance of its interpretation. In his poem “Introduction to Poetry,” he writes: “all they want to do is tie the poem to a chair with rope/and torture a confession out of it./They begin beating it with a hose/to find out what it really means.”

The point of reading a poem is not to try to “solve” it. Still, that quantifiable process of demystification is precisely what teachers are encouraged to teach students, often in lieu of curating a powerful experience through literature. The literature itself becomes secondary, boiled down to its Cliff’s Notes demi-glace. I haven’t wanted to risk that with the poems that enchanted me in my youth.

Teachers should produce literature lovers as well as keen critics, striking a balance between teaching writing, grammar, and analytical strategies and then also helping students to see that literature should be mystifying. It should resist easy interpretation and beg for return visits. Poetry serves this purpose perfectly. I am confident my 12th graders know how to write essays. I know they can mine a text for subtle messages. But I worry sometimes if they’ve learned this lesson. In May, a month before they graduate, I may read some poetry with my seniors—to drive home that and nothing more.