On the morning of 12 January 1989, I had arranged to meet Shane MacGowan outside the Pogues' management office in Camden Town at 11am. He arrived just after midday, besuited and freshly shaven, with razor nicks all over his chin to prove it. He was carrying a pack of Kraft cheese slices and a two-litre bottle of white wine.

Even by his usual standards, he seemed somewhat altered – preoccupied and fidgety, his conversation even more disconnected and tangential than usual. I hailed a taxi and we headed for the Montague Arms in south-east London, where Nick Cave and Mark E Smith of the Fall were waiting alongside music journalist James Brown and photographer Bleddyn Butcher. The occasion was a so-called "summit meeting" cooked up by Brown, who was then features editor of NME, where Butcher and I also worked.

It soon became clear that MacGowan was nervous at the thought of meeting Cave, whose music he revered, particularly the mutant swamp blues of Cave's former group, the Birthday Party. The wine, and whatever else he had ingested that morning, was his way of calming his nerves. The cheese slices were his nod to breakfast. When we finally arrived at the pub, he disappeared into the loo for 15 minutes and returned looking miraculously refreshed.

The ensuing interview, which began two hours later than scheduled, meandered on for at least another three hours, fuelled by alcohol and, as the afternoon drew on, amphetamines. (Throughout, the newly clean Cave, much to Smith and MacGowan's surprise, stuck steadfastly to mineral water.) Edited, but still fractured, a transcript was published in NME in late February 1989, under the heading The Unholy Trinity. It has since attained a kind of semi-legendary status among music fans of a certain vintage.

In truth, though, it was a messy and inconclusive affair, with Cave as the still centre of the often fractious exchanges triggered by the wilfully provocative Smith. A cacophonous jam session on the pub's small stage concluded the proceedings with Cave on organ, Smith on guitar and MacGowan on drums – I still have a cassette recording somewhere – before we reconvened in Brown's Camberwell flat, where the portrait of the three on this page was taken. Two things strike me about the photograph: it captures a calmness and a sense of good-natured camaraderie that were not otherwise evident that day; and it marks the first meeting of Cave and MacGowan, the moment their ongoing friendship began.

Twenty-five years later, it is Cave who remains the most consistently creative of the three men, his self-discipline and dedication to the craft of songwriting undimmed by the years of excess that the other two doggedly self-destructive mavericks have followed. When not recording or touring, he famously goes to his office every day to write.

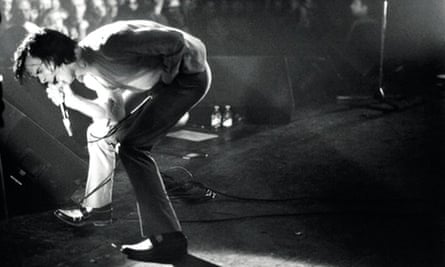

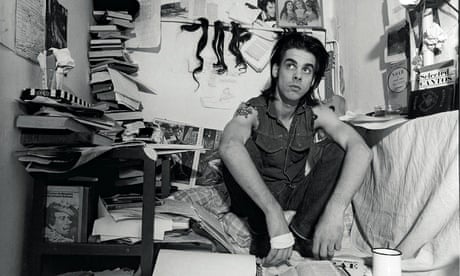

In his photobook A Little History: Nick Cave & Cohorts, 1981-2013, Bleddyn Butcher, a fellow Australian who first shot Cave in 1981, traces the arc of Cave's singular creative life. His images move from the visceral – the young Cave lying outstretched on stage at a typically implosive Birthday Party performance in 1981 – to the reflective – Cave performing solo at the piano at an intimate show in Ireland in 1997. In between, we see Cave grow older, more sure of himself, his vocation and his place in the bigger picture.

It is coincidental that this retrospective book, and the exhibition that accompanies it at Somerset House, London next month, is published just as an often dramatically illuminating film about Cave is released. Directed by the artists Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, 20,000 Days on Earth, co-scripted and featuring a voiceover by Cave, is a merging of fly-on-the-wall documentary, drama, biography, confessional and art film. In it, Cave appears as both a willing subject to be dissected and an artful curator of his own myth and persona.

For all its artifice, the film has passages that reveal much about Cave's way of working and, more surprisingly, his colourful personal history. Driving around Brighton, where he lives with his wife, the former model Susie Bick, and their two sons, Cave converses with various backseat passengers, including his former guitarist Blixa Bargeld, actor Ray Winstone and Kyle Minogue. The stylised, almost noirish tone of these interludes is fractured from time to time by Cave's honesty – he still seems pained by Bargeld's abrupt departure from the Bad Seeds in 2003 – and articulate musings on his music. When Winstone asks him if he still loves performing, he says without hesitation: "I live for it."

An extended sequence, in which Cave submits to a therapy session with the psychoanalyst Darian Leader, is the film's most staged and yet most revealing passage. The question "What do you fear the most?" elicits a heartfelt response that touches on his own mortality: "It does worry me that I'm going to be able to continue to do what I do and reach a place that I'm satisfied with." Mention of his father's death, which happened suddenly when Cave was 19, brings forth a look of utter pain and still-lingering incomprehension. It is these moments that make 20,000 Days on Earth such a revealing film about Cave, his creativity and the discontents that often fuel it.

Those discontents powered Cave's early unruly performances, which often seemed like attempts at self-exorcism. In Butcher's photographs of the Birthday Party performing in the early 80s, he looks stick-thin and angular – Rimbaud with a shock of black hair and a demon's howl. Back then, photoshoots would often be derailed by, in Butcher's words, "fights, punchings, bashing, idiocy and ODs".

As the book's chronological narrative unfolds and Cave's songwriting style becomes both more formally composed and more reflective, Butcher's photographs shift in style. The group, too, become more at ease as subjects, but it is the main character who is the constant, commanding presence.

These days, as Forsyth and Pollard's film shows, a Nick Cave performance turns on the promise of transformation – ours and, perhaps even more importantly, his. "Look at me," he sings on a recent song, Jubilee Street, as the film-makers capture him on stage and in his element, "I'm transforming, I'm vibrating, I'm glowing, I'm flying… look at me now…" There is a level of ironic self-awareness here, too, the performer acknowledging how much he needs the audience – and the film-makers and the photographer – to keep looking at him even as he takes flight to that unselfconscious place where, as he memorably puts it, he can create "those moments when the gears of the heart really change".

For a performer who first sensed the importance of a persona when as a child he saw Johnny Cash perform on television, Cave still walks the line in a singular and often self-revelatory way. A bad seed made good.

A Little History: Photographs of Nick Cave & Cohorts 1981-2013 by Bleddyn Butcher is published by Allen & Unwin (£18.99). Click here to buy it for £15.19 with free UK p&p. The exhibition is at Somerset House, London, from 3-28 September. 20,000 Days on Earth is released on 19 September

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion