KARNES CITY — On a quiet morning in late July, three biologists moved slowly along a weedy alley near the city water tower, scanning for signs of an iconic native creature that most Texans never will see.

To a rolling serenade of barking backyard dogs, they probed the litter, old beer bottles and underbrush with long metal rods. Then suddenly, with a yelp of triumph, one held up her prize: A large female Texas horned lizard.

“It’s my first one of the summer. It’s hard, especially when you have to chase them. But when you catch them, it’s exciting,” said Daniela Biffi, 35, a graduate student at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, home of the purple “Texas Horned Frog” athletic teams.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

When a quick electronic scan of the squat reptile showed it did not already have an implanted microchip, and thus had not been captured before, there was more cause for celebration.

The horned lizard — more commonly known among Texans as the horny toad — was quickly measured, photographed, probed for a DNA sample, given a microchip and released.

The information will be added to a database on about 600 animals found in Karnes County, about 60 miles southeast of San Antonio, since the TCU Horny Toad Project began here in 2013.

“The overarching question is how do the horned lizards co-exist with people in these small towns when they have disappeared from so many other places,” said TCU biology Professor Dean Williams, whose team is studying the lizards’ home range, genetics, diet and habitat features.

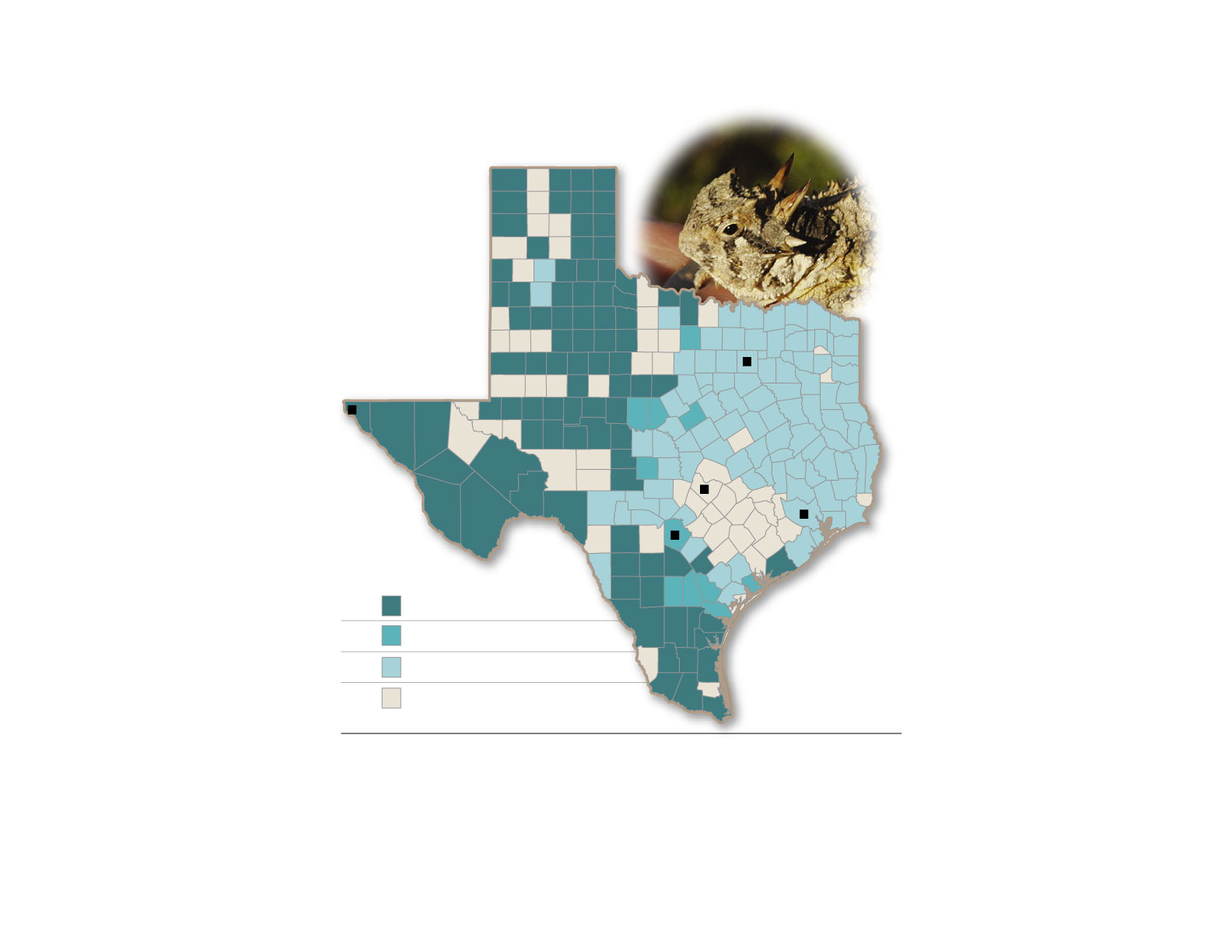

Finding

the Texas

horned

lizard

Sightings by

Texas Parks and

Wildlife

biologists,

Dallas

2004- 2006

El Paso

Austin

Houston

San Antonio

Sighted by all

Sighted by some

Sighted by none

No results

Source: Texas Parks and Wildlife, wikiwand.com

Mike Fisher/San Antonio Express-News

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

The Karnes County project also may help solve a question that vexed biologists and saddened older Texans for decades. Whatever happened to all the horny toads that once played so rich a role in Texas popular culture?

As common as ants and grasshoppers over most of Texas just decades ago, they long since have vanished from much of their original range.

“Historically, they were all the way into East Texas, and abundant in Central Texas, but they have basically receded back to 50 miles west of the I-35 corridor. They are still common in the Panhandle and West Texas, and there are some in South Texas, but they are down to 50 percent or less of their historic range,” said Nathan Rains, a wildlife diversity biologist with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

In response to the decline, TPWD, in cooperation with various Texas zoos, has been trying to establish captive breeding programs for reintroductions in the wild.

This summer, the San Antonio Zoo joined in the effort and already has begun collecting lizards for its planned breeding program.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“They are so darned cool, so charismatic, and people who grew up with them adore them. And if they didn’t, they are on their bucket list of something to see,” said Andy Gluesenkamp, the zoo’s director of conservation and research and a former Texas state herpetologist.

Although many culprits are suspected in the population collapse of the Texas state reptile, including loss of habitat, imported fire ants, pesticides and overcollection, no single “smoking gun” cause has emerged.

“I think its a combination of four or five factors that decimated the horned lizard population, not just fire ants and loss of habitat,” said Rains, who said applying pesticides indiscriminately to kill ants also likely was a critical factor.

“They are a diet specialist, an ant eater. So, no food, no habitat, no lizards,” he added.

So far, Rains said, the results of small releases of mature horned lizards at remote sites in Brown, Mason and Parker Counties over the past four or five years has not led to new established populations. Many of the lizards, which carried radio transmitters, were quickly eaten by predators including racoons and snakes, and few survived long enough to reproduce.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

The strategy, he said, now is shifting toward making much larger releases of very young lizards, so that even if the initial mortality is high, enough will survive to establish a viable population.

“We’re looking at producing 400 to 500 babies in a captive environment and then releasing them in the wild, flooding the environment with lizards,” he said.

At the San Antonio Zoo, Gluesenkamp plans to establish a “lizard factory” to generate large numbers of babies. Already, 28 tiny newborns, looking like miniature dragons, are skittering around in glass tanks, gobbling pinhead crickets.

Five adult horned lizards, collected at the Chaparrel Wildlife Management Area near Cotulla, also are being kept in the repurposed zoo warehouse.

Gluesenkamp hopes to eventually have a captive breeding population of 50 adults. And with each female producing an annual clutch of 10-30 eggs or more, the possibilities are staggering.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

So are the costs and logistics, he said.

“If we’re going to be raising hundreds, the feeding becomes the major concern,” he said.

The zoo currently buys harvester ants and other insects from suppliers, spending about $170 a month to sustain just a handful of animals. With the zoo’s horned lizard population projected to grow exponentially, the cost will also.

To mitigate this, Gluesenkamp intends to establish some in-house harvester ant colonies.

He also hopes the public finds the project worthwhile and the zoo eventually will have horned lizards on display for visitors.

“Most of the funding we’ve received so far for this project has been unsolicited donations from the public,” he said.

A legendary critter

One of 17 species of horned lizards that range from Canada to Guatemala, the Texas Horned Lizard is one of three species found in Texas. Its current range extends west into Arizona, north to Kansas and south into Mexico. It once may have included enclaves in Arkansas and Louisiana.

Alarmed by its decline, the Texas Legislature in 1967 passed a law banning the collection, export and sale of horned lizards.

A decade later, the creature was listed as “threatened” in Texas. In 1993, it became the state reptile.

For many Texans who grew up between the 1950s and the 1970s, the horny toad was a charming childhood companion, easily caught and made a pet.

In his book, “Ye Legendary Texas Horned Frog,” author June Welch wrote, “To live in Texas in my time was to know the horny toad as part of the friends and furniture of the world.” But when the book was published in 1993, they already were gone from many areas.

Welch also wrote about “Old Rip,” the legendary toad from Eastland that allegedly survived 31 years entombed in a cornerstone of the county courthouse.

After Old Rip’s miraculous story broke in 1928, it spread nationwide as prominent scientists and true believers argued about its veracity. President Calvin Coolidge had an audience with Old Rip on the toad’s national tour.

Old Rip’s preserved corpse still is on display in Eastland and the argument over his story continues.

But if nothing more, the Lazarus of toads introduced the Texas Horned Toad to the rest of the nation, likely contributing to its popularity to collectors and retailers. It also inspired an Old Rip festival held annually in Eastland, even though no native horned lizards have been seen there for decades.

In 1990, a group of concerned Texans in Austin formed the Horned Lizard Conservation Society in response to the crisis.

One of the group’s founders, Bill Brooks, 65, since has spent much of his time fighting the good fight, with mixed results.

“We got together at our first little meeting in Zilker Park in Austin, and said, ‘Let’s save the horned lizard,’ But it’s a lot easier to say it than do it,” he said.

Today, almost three decades after the society was formed, and despite persistent efforts to stem the creature’s decline, Brooks isn’t sure how it will all end.

“If I look at the big picture, it seems to be in decline. They are a lot less than they used to be. The hardest thing I have to do is get kids to care about something they have never seen,” he said.

For Brooks, the fight always has been very personal, as horny toads were a big part of his childhood in northwest San Antonio.

“You could find them whenever you wanted to. In San Antonio they were inside of 410,” he said.

“At one time, when I was about 8 years old, I went out with about six of my friends to see how many we could catch in a weekend. And we caught 100 of them. They were that common,” he said.

But around the time he went away to college in the early 1970s, they began to disappear. By the time he came back, they were gone from his home neighborhood around Wayside Drive.

At the society’s recent biannual meeting in Goliad, about two dozen members, presenters and visitors turned out to hear talks on the captive breeding and reintroduction efforts, taxonomy and related subjects.

Wade Phelps, a dentist in Kenedy, wore a shirt advertising the city as “The Horned Lizard Capital of Texas,” a designation received from the Texas Legislature in 2001, when they were abundant.

The story had begun a little earlier, when Kenedy resident Joe Lang called the Horned Lizard Conservation society to help him remove horned lizards from around a house he intended to fumigate. More than 90 were quickly captured and moved.

Th city saw the opportunity to claim a distinction, and a local Horned Toad Club was founded. But like other horned toad stories, it did not have a happy ending.

Once so plentiful in Kenedy that locals offered guided tours to visiting horny toad tourists, the fierce-looking creatures are now rarely seen there, even by the TCU team of sharp-eyed scientists.

And although the cause of the dramatic decline in Kenedy no doubt is complex, likely including a drought, urban cleanup brought by the Eagle Ford Shale boom and other factors, perverse human nature may have played a part.

“We were trying to share the horned lizards with the public, but we had people picking up lizards and carrying them off,” Phelps said.

HLCS President Jared Fuller, 31, a graduate student at the University of Nevada at Reno, said that as the group’s members ages, membership has dipped to just over 200 people.

“We’re too small as an organization to save the horned lizard, but if you don’t have public support for whatever animal you are trying to save, it’s a doomed effort,” he said.

Small as a dime

During their morning search in Karnes City in late July, the scientists from TCU eventually found eight horned lizards, including two babies.

When they searched in Kenedy that evening, they found no lizards and barely any sign of scats, as droppings are known.

The show-stopper was a pale baby lizard that weighed only 1 gram, and was barely larger than a dime. It quickly drew oohs and aahs from the researchers.

“He’s so … precious. These are the pictures you show everyone when you go back home,” Rachel Alenius, 23, a TCU graduate student, excalimed as she snapped away with her smart phone.

One of the notable findings thus far of the TCU project is that the urban remnant populations in Karnes County are genetically different.

“They are really isolated in small towns. It’s almost like an island. If you look at horned lizards on either side of major roads in Karnes City, you can find genetic differences. The roads act as barriers,” Williams said.

On their walks through the back alleys of Karnes City, the scientists often meet and talk with residents about their research project and horned toads in general.

On this particular morning, they caught one next to the backyard of Wayne Wishert, 81, who paused beside his garden fence hanging with blooming Queen Anne’s Lace to watch the action.

The toad was a fighter, and squirted Biffi with blood from its eye socket, surprising her but not enough to shake her loose. The peculiar defense mechanism of horned lizards works better on dogs, foxes and other canids that find the red fluid highly distasteful.

Wishert said he regularly sees the prehistoric-looking creatures in his yard and garden, where they lay eggs, and has to be watchful when backing out of his carport.

“I see them daily. We’ve got one of the three-legged variety. He’s taken up residence near the air conditioner,” he said.

“They’re part of the South Texas wildlife. They hurt nothing and are a pleasure to observe. As children we used to turn them over, rub their bellies and play with them,” he added.

A little later, while patrolling a different alley, the group members encountered Harold Franke, 77, who came quickly to his back fence to check them out.

Assured that nothing was amiss, Franke visited for a few minutes on horned toads. He said he regularly mows the alley, keeping an eye peeled for them, including one that lives near the corner.

Franke also mentioned a particular horned toad that has settled in close to the modest dwelling he bought more than three decades ago.

“There’s one that stays by the side of the house. I see him about once a week, and I’d protect him with my life,” he said with conviction, adding: “A lot of people don’t think nothing about anything except having a cellphone and a vehicle to go down the road at 70 miles an hour, but I’m from the old school.”

jmaccormack@express-news.net