In 2006, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) submitted a list of regulations to the White House aimed at helping China get into the U.S. chicken market by certifying Chinese facilities to process U.S.-raised poultry for sale back in the States.

Tony Corbo, a lobbyist at the nonprofit public interest organization Food and Water Watch, followed the decision closely, because food processing in China was notoriously poor. Chinese authorities had identified insecticide-soaked hams, soy sauce made from human hair and, in 2004, fake milk powder that gave babies the sometimes fatal "big head disease" (so named because it caused their heads to swell and bodies to wither). Normally, Corbo says, such a decision from the White House could take "months if not years" to come through. But just one day later, the White House gave its approval. Corbo was puzzled until, the following morning, China's president at the time, Hu Jintao, visited then U.S. president George W. Bush in Washington, D.C. "[The approval] was a gift," Corbo concluded. But for what, exactly, wasn't clear.

After the ruling, USDA inspectors went to China and determined that Chinese poultry plants were eligible to process U.S. chickens. But food problems persisted in the country. Before the year was out, people in China were sickened by fish tainted with illegal antibiotics, vegetables covered in pesticides, snails infected with meningitis and poultry carrying the avian flu virus. Congress voted to completely defund the USDA's poultry inspections of Chinese imports.

Soon China's certification lapsed, but it appealed to the World Trade Organization, which ruled in 2009 that Congress's treatment of the country was unfair. Funding was restored and the process of approval began again. A series of USDA audits followed, all of which found China unfit to process U.S. poultry. Then, in 2013, without further inspection, the agency granted four Chinese plants certification. "It seems China is continually getting to the head of the line," Corbo says.

Between 2006 and 2014, China's food industry continued to scare people. As Representative Christopher Smith, R-New Jersey, noted in a June 2014 hearing on Chinese food issues, the country produced "meat that glows in the dark, exploding watermelons, bean sprouts containing antibiotics, rice contaminated with heavy metals, mushrooms soaked with bleach, and pork so filled with stimulants that athletes were told not to eat it lest they test positive for banned substances." Since 2007, more than a 1,000 dogs in the U.S. have died after eating Chinese-made pet food containing poultry. "[The FDA has] tested for all the pathogens they know of," says Barbara Kowalcyk, the Senior Food Safety Risk Analyst at RTI International, a nonprofit research organization. "There is something in there causing dogs to die. It's baffled officials here in the U.S. for years. Why on earth would we allow it to come into the U.S. for human consumption?"

Beyond the health concerns, there also doesn't seem to be any reason to ship chicken to and from China for processing. It "probably doesn't make any economic sense," says Jim Sumner, president of the USA Poultry and Egg Export Council, a nonprofit, industry-sponsored trade organization. According to Sumner—who has visited USDA-approved plants in China and would "put them up against any I've seen anywhere" in terms of cleanliness—"the biggest if not only advantage would be cost of labor." Compared with fish, which is sent from America's West Coast to China for deboning and processing, getting chicken from farm to table is far less labor-intensive, so the savings in labor costs don't seem to beat the expense of shipping chickens back and forth across the ocean. As Mike Martin, director of marketing for Cargill, a meat producer that produces poultry in Europe but does not sell it in the U.S., put it to Newsweek, economically speaking, "it's a head-scratcher."

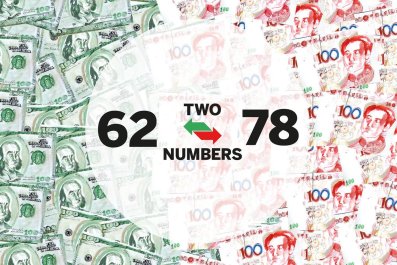

China agrees. According to a report issued by the USDA's Foreign Agricultural Service in 2007, after the agency's ruling opened the door for China to process U.S. poultry, China's equivalent of the USDA stated that "this trade is not economical.… Rising international broiler [the subspecies of chicken most commonly raised for meat production] prices and international transportation costs, combined with the unfavorable exchange rate, make re-exports uncompetitive."

In 2013, in the months before the USDA approved the four Chinese plants to process chickens for the U.S. market, of the country's four major chicken companies—Tyson, Pilgrim's Pride, Sanderson Farms and Perdue Farms—only Tyson lobbied the USDA for "market access for chicken to China" (and other countries). Neither the National Chicken Council nor the U.S. Poultry and Egg Association put any money toward the cause. When asked about the USDA's decision to allow China to process chickens for the U.S. market, a Tyson spokesperson told Newsweek, "All of the chicken we sell in the U.S. is raised and processed here in the U.S. We have no plans to import chicken from China."

So why did Tyson lobby the USDA? Corporations are not required to disclose in detail their reasons for supporting specific issues, but in an email to Newsweek, Tyson says that the lobbying efforts reported in 2013 were around trade and tariff issues for the export of U.S.-produced products into China and not related to the import of poultry products produced in China. It also sought to have Chinese import bans lifted from two major poultry producing states. Tyson Foods and other major poultry producers like Pilgrim's owner JBS are also among the largest beef processors in the country. And in 2009, the companies, along with other large beef and chicken processors and the U.S. Cattlemen's Beef Association, were among more than 50 companies and organizations that signed a letter to U.S. President Barack Obama asking him for support of "regulation governing the importation of cooked poultry products from China," and advocating for open markets for international trade.

When asked about the USDA's ruling, people in the beef and chicken industries, as well as food activists and Representative Rosa DeLauro, D-Connecticut, who is fighting to keep Chinese-processed chickens out of school lunches, all told Newsweek that, in DeLauro's words, "it's all about the beef."

The beef industry's interest in Chinese chickens dates back to 2003, when a cow in Yakima, Washington, was determined to have mad cow disease. Around the world, countries were quick to respond. Japan, the top foreign consumer of U.S. beef, banned its importation. So did Mexico, South Korea and a score of other countries—China among them. In time, all of these governments reversed their bans except for China.

It is now widely believed that the beef ban is now simply a tactic for China to gain access to the U.S. chicken market. Indeed, a 2007 report issued by the FDA indicates that the country would much rather be able to sell its own chickens in America. "They're holding U.S. beef hostage," says DeLauro, "a quid pro quo: U.S. beef in exchange for Chinese chicken."

The problem is that because the USDA has the "dual mission to promote U.S. products and safety," it is easily swayed by these types of tactics, says DeLauro. "When it comes to the USDA, it's all about trade trumping safety. It's all about profits. It's pretty outrageous."

The U.S. beef industry, worth $44 billion, is far more profitable than the American chicken industry. Though pork has traditionally dominated the Chinese market—more than half of the world's pork is consumed by China—beef is on the rise there. While beef has historically been considered a luxury good in China, beef consumption has grown by more than 5 percent in the past year, and demand is expected to keep rising. In response, foreign companies are scrambling to get in on the boom. In the past year, Canada's beef exports to China have multiplied six times; Australia, the largest exporter to China, has multiplied its exports by four times; meanwhile, the U.S. still can't send its beef to China.

For the U.S. meat industry, the appeal of the chicken-for-beef trade is clear. Profits from the potential exportation of beef to China, Sumner says, "far exceed" the potential losses in giving up a share of the American chicken market. The motive for China selling its chickens in America is less clear. As Sumner explains, the U.S. is the largest producer of both corn and sorghum, which are the major ingredients of chicken feed. "Feed is 60 percent of the cost of a chicken," he says. "Whoever produces the cheapest feed produces the cheapest chicken. That'd be us." That means that even if China is able to sell its chickens in the U.S., it's unlikely it would undercut its American competitors.

Still, activists worry that giving China access to the U.S. chicken market—either to process American-raised poultry or, eventually, to sell its own—is a dangerous gambit, given the Chinese government's poor track record enforcing food safety regulations. For example, in the years leading up to 2008, Chinese customers had been complaining that milk purchased from one of China's largest dairy companies was making children sick. For some reason—either corruption or negligence—officials ignored these concerns. It was only after a foreign shareholder in the company complained to Chinese officials in Beijing that the milk was finally pulled from the market. Eventually, the government prosecuted those involved in the scandal. But for Kowalcyk the response was too late. "The Chinese government shot the people who did that," she says—but not before six infants were killed and more than 50,000 babies were hospitalized. "I can't even imagine who would put melamine in baby formula.

"There are huge problems with China's food safety," she adds. "They're just not there yet."

Correction, September 29, 2014: This text was corrected from an earlier draft version of the article accidentally published due to a production error.