Perusing The New York Times archives a few days ago, I stumbled upon a delightful news nugget from 1858 about the "benefits and evils" of the transatlantic telegraph—delightful, because it reads like it could have been written today by a print nostalgist about the benefits and evils of the Internet.

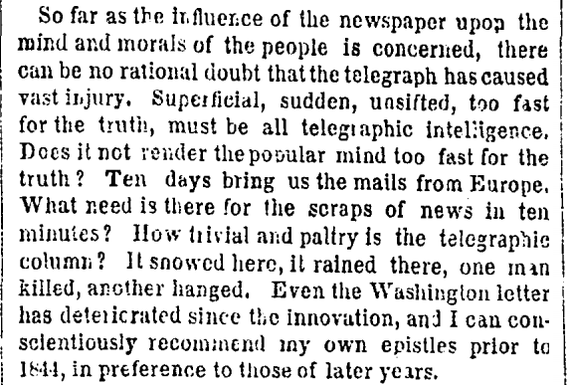

Just try replacing "telegraphic intelligence" with "Twitter" or "online news," and you'll see what I mean:

"Superficial, sudden, unsifted, too fast for the truth, must be all telegraphic intelligence. Does it not render the popular mind too fast for the truth? Ten days bring us the mails from Europe. What need is there for the scraps of news in ten minutes? How trivial and paltry is the telegraphic column?"

The article was published on August 19, 1858, three days after the completion of the first successful test of an undersea cable that made North American communications with Europe possible in minutes rather than days. More from the Times: "That it will be of very great use cannot be questioned, but how will its uses add to the happiness of mankind? Has the land telegraph done any good? Has it banished any evil, mitigated any sorrow?"

Early newspaper references to the telegraph are marked with distrust for the technology. "The telegraph is not a very clear narrator of facts," the Times wrote in 1861, later writing that it made people "mourn for the good old times when mails came by steamer twice a month." (In the years that followed, the telegraph would play a key role in the Civil War.)

Anti-tech criticism isn't wrong—there are plenty of legitimate warnings about how the ease with which anyone can publish something today can exacerbate problems in accuracy and ethics. But that also doesn't mean previous technologies were inherently better, or that they'll ever reclaim their standing.

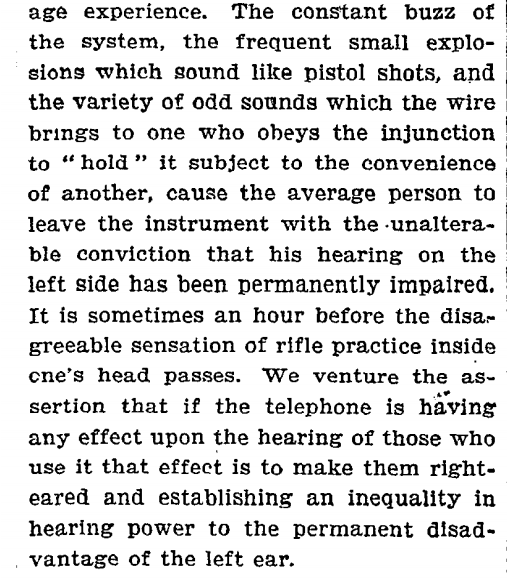

News archives, of course, are full of distrust for technologies we've long since abandoned or now take for granted. In the early days of the telephone, people were told that the device was creating a "race of left-eared people—that is, of people who hear better with the left than with the right ear," according to the Times in 1904. Incidentally, the paper disagreed with the research it reported, and suggested that the telephone was instead permanently impairing hearing in whatever ear—left, usually—people used most often when telephoning.

By 1913, the Times declared the telephone was "in no way harmful"—not physically, that is—only that it was ruining everyone's good manners:

"But somehow we do not regard telephoned invitations with the same reverence we bestow on other invitations. Few of us would fail to keep an engagement which had been suggested to us by means of an engraved invitation. Few of us would neglect a written invitation. But many of us will say, at the last minute, if we are too tired to feel enthusiastic about some social gathering to which we have been bidden by telephone..."

The newspaper also complained that the telephone had turned the art of writing love letters into a "despised necessity."

The radio, in 1924, was debatably a nuisance that produced "loud and unnecessary noise." Then came television, which was dangerous because it was too spellbinding. Oh, and because, as the Times reported in 1937, people reported being spied on through their TV sets.

Fast forward a few decades to when the Sony Walkman was introduced, and complaints about music in public spaces as a nuisance were replaced with fears that personal cassette players would make us all antisocial—a chorus that was revived when the iPod came out years later.

And, of course, there's the Internet, which has been blamed for all the antisocial, privacy erasing, time sucking, superficial depravity of its technological predecessors combined.

"Has the Internet been overhyped?" the Times asked in 1994. Twenty years later, though we're still debating its benefits and its evils, the answer is clearly no.

Looking back, it seems that anxiety about technological advances is often wrapped up in how a new technology disrupts our expectations about time—it's too fast!—and control. Marvels in modern technology have repeatedly connected us in ways that once seemed impossible. And it is that connectivity—the sense of something bigger than the individual, the networks that upend perspectives of time and scale—that makes so many people uneasy. Here's how media scholar Marshall McLuhan put it in a 1979 lecture:

What is desperately needed is a kind of understanding of the media which would permit us to program the whole environment. If you understand the nature of these forms, you can neutralize some of their adverse effects and foster some of their beneficent effects.

Or maybe it's just that people like what they know. And that humans, for as inventive and adaptable as we are, don't always like change. McLuhan explained that it was, back in 1979, as it is now: "Nostalgia is the name of the game in every part of our world today."