- India

- International

The light fantastic: A glimpse of Bangladesh through photographer Sarker Protick’s eyes

Bangladeshi photographer Sarker Protick’s work offers intimate glimpses of his country.

In 2015, Protick won the World Press Photo award for What Remains, an intimate series on his ailing grandparents.

In 2015, Protick won the World Press Photo award for What Remains, an intimate series on his ailing grandparents.

On a hot afternoon in 2009, a bored college student in Dhaka, Bangladesh, pointed his cellphone camera at the sun and took a photograph. His phone crashed within minutes, trapping within it several of his other photos. This was Sarker Protick in 2009, a 23-year-old studying business management, with his heart set on music. But he persisted with photography and bought a basic DSLR camera.

In 2015, Protick won the World Press Photo award for What Remains, an intimate series on his ailing grandparents. With his camera set on a tripod, and long exposure that let more light in, the series on John and Prova — cancer and heart patients, respectively — consists of photographs in which the dominant mode is white, lending them an almost angelic mien. “When I started taking their pictures, they had something to look forward to. My relationship with them changed, as did the way I look at people their age,” says Protick. Prova passed away months after her grandson began shooting her. “When their illness worsened, I stopped shooting them. They looked so vulnerable, and I didn’t want to share that with the world,” he says.

A photograph from Of Rivers and Lost Lands, a series on the Padma.

A photograph from Of Rivers and Lost Lands, a series on the Padma.

Since he took up photography seriously in 2011, Protick’s work has stood out from the clutter. It represents a new, more intimate way of looking at Bangladesh. “The traditional approach focusses on the misery here — acid attack victims, collapsing governments, and so on. That work is also mostly in black-and-white, while mine isn’t,” says Protick. What Remains won the World Press Photo award for a deeply personal story. “When I get an award like this, I feel as if the world is ready and eager to see this nation in a different light,” says Protick.

At the Delhi Photo Festival earlier this month, validation came in the form of crowds thronging his exhibition on the lawns of IGNCA. Starkly different from What Remains, this one had a rather bright colour palette. Love Me or Kill Me is a series on Dhallywood, the Dhaka film industry, but not its stars. With tight budgets, OTT costumes, dramatic action sequences and linear storylines, Protick found an industry in flux. “More than the lead actors, what really interested me were the extras, those behind the scenes, the fake-gun-toting gang members. They act and also work in the production team,” he says. While working on the series, he also ended up acting in a movie called Warning where he plays a journalist. “It’s just a small appearance. I was a asked to play a journalist because I walked around the set with a camera. And also because I have a beard,” says Protick. The series was exhibited at the Paris Biennale.

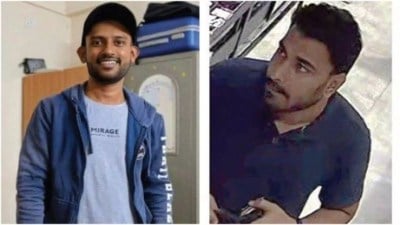

An image from Protick’s series on the Dhaka film industry.

An image from Protick’s series on the Dhaka film industry.

All of his series are works in progress, and Protick keeps going back to them every few months. “Not taking pictures is also a part of photography. Sometimes you just have to forget about it and look at it from a fresh perspective later on,” says Protick. Currently, he is back to shooting Frantic, an early-2014 series on his relationship with Dhaka, and the people who are building it.

Like most of his generation, Protick is a product of the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute. In 2009, with a DSLR in hand, but little idea of what to do with it, he applied for a three-year-long photography programme there at an uncle’s suggestion. In 2011, a visit to Chobi Mela, Bangladesh’s premier photography festival, inspired him to pursue the art form more seriously. He now teaches two courses at Pathshala and curated a projection of works by his students at the photo festival in Delhi recently. The recurring theme in Protik’s work is death and disappearance — from What Remains to the fake blood splattered on the floor in Love Me or Kill Me, from the disappearing banks of the Padma in Of Rivers and Lost Lands to his love-hate relationship with a city losing its innocence in Frantic. “Loss is a part of me. It has had a mark on my life, it haunts me. Death is every artist’s fetish because it’s the ultimate thing,” he says.

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05