The Paradox of Baby Names

Even as parents go to ridiculous lengths to ensure an original name for their child, the annual most-popular list documents how unconventional names have become the norm.

There is a company that promises to come up with a list of names for your new baby that are—as much as baby names can possibly be—unique. Erfolgswelle, based in Switzerland, employs 14 naming experts, 12 translators, and four historians, as well as two trademark attorneys who work to ensure that baby names don’t conflict with existing companies and products. All of these professionals—for the hefty sum of $31,000—will spend around 100 hours generating a list of 15 to 25 unique-ish names for new parents to choose among as they’re naming their new bundles of joy. (Joy, which as of 2014 was the 462nd most popular girls’ name in the United States, will ostensibly not be included on such a list.)

Erfolgswelle has a business not just because there are people in the world with $31,000 lying around to finance its services, but because there can be a game-theory component to baby-naming. While some parents choose traditional names for their kids, and many others choose family names, and many others choose names that have been lifted from pop culture—Khaleesi has risen in popularity over the past couple of years—many other new parents seek unusual names that, they hope, will help their kids stand out rather than fit in. As the sociologist Philip Cohen put it, exploring the precipitous decline of the name Mary in recent years, “Conformity to tradition has been replaced by conformity to individuality.”

And the web, it seems, has exacerbated that trend. As Laura Wattenberg, author of The Baby Name Wizard, told The Seattle Times, “The Internet encourages people to think of baby names like user names. Once a name is taken, they think, ‘That’s it—I have to find a new one.’”

The challenge for parents who want to unique-name their kids, though, is that they’re doing their name-seeking at the same time as all the other parents who are seeking to unique-name their kids. And names being what they are—pretty much permanent—naming becomes both a gamble and a kind of leap of faith. You don’t know what other parents have settled on in their own quest for individuality until the Social Security Administration, after all the naming has been done, comes out with its annual data about the popularity of kids’ names. There’s an actuarial element to all this. You’re trying to predict naming trends in order to fight against them—but you’re doing it as the trends are being created.

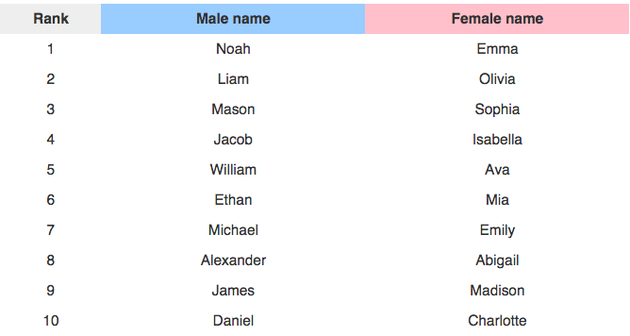

I mention that because the SSA just came out with 2014’s list of names. And the most popular are names that, up until fairly recently, were the unusual choices: Emma, Noah, Olivia, Liam.

Let’s look at Emma. Emma didn’t enter the top 100 names in the United States until 1993. It rose to the top 10 in less than ten years—2002. And in 2008, it became the most popular name for all girls. Emma went from “distinctive” to “common” to “incredibly common,” all in the relatively short span of two decades. It remains a beautiful name; it does not remain, however, an unusual one. The opposite.

Noah took a similar path. So did Olivia. So did Liam. (So did, I am reminded every time someone mistakenly takes my Starbucks coffee, Megan.) The names parents selected, presumably, at least in part for their uniqueness became, in short order, the opposite of unique. Quirk became standardized—and trendy. As a result, as the premium of unusual names grows, parents have to try even harder to choose names that will distinguish their kids. They look to lists like the SSA’s not for ideas for names, but for ideas for names to avoid. As Laura Wattenberg noted, “I often have people saying to me, ‘I’m ruling out any name in the top thousand.’”

Megan Garber is a staff writer at The Atlantic.