Fish Skin for Human Wounds: Iceland’s Pioneering Treatment

Six hours north of Reykjavik, along a narrow road tracing windswept fjords, is the Icelandic town of Isafjordur, home of 3,000 people and the midnight sun. On a blustery May afternoon, snow still fills the couloirs that loom over the docks, where the Pall Palsson, a 583-ton trawler, has just returned from a three-day trip. Below the rust-spotted deck, neat boxes are packed with freshly caught fish and ice. “If you take all the skins from that trawler,” says Fertram Sigurjonsson, the chairman and chief executive officer of Kerecis Ltd., gesturing over the catch, “we would be able to treat one in five wounds in the world.”

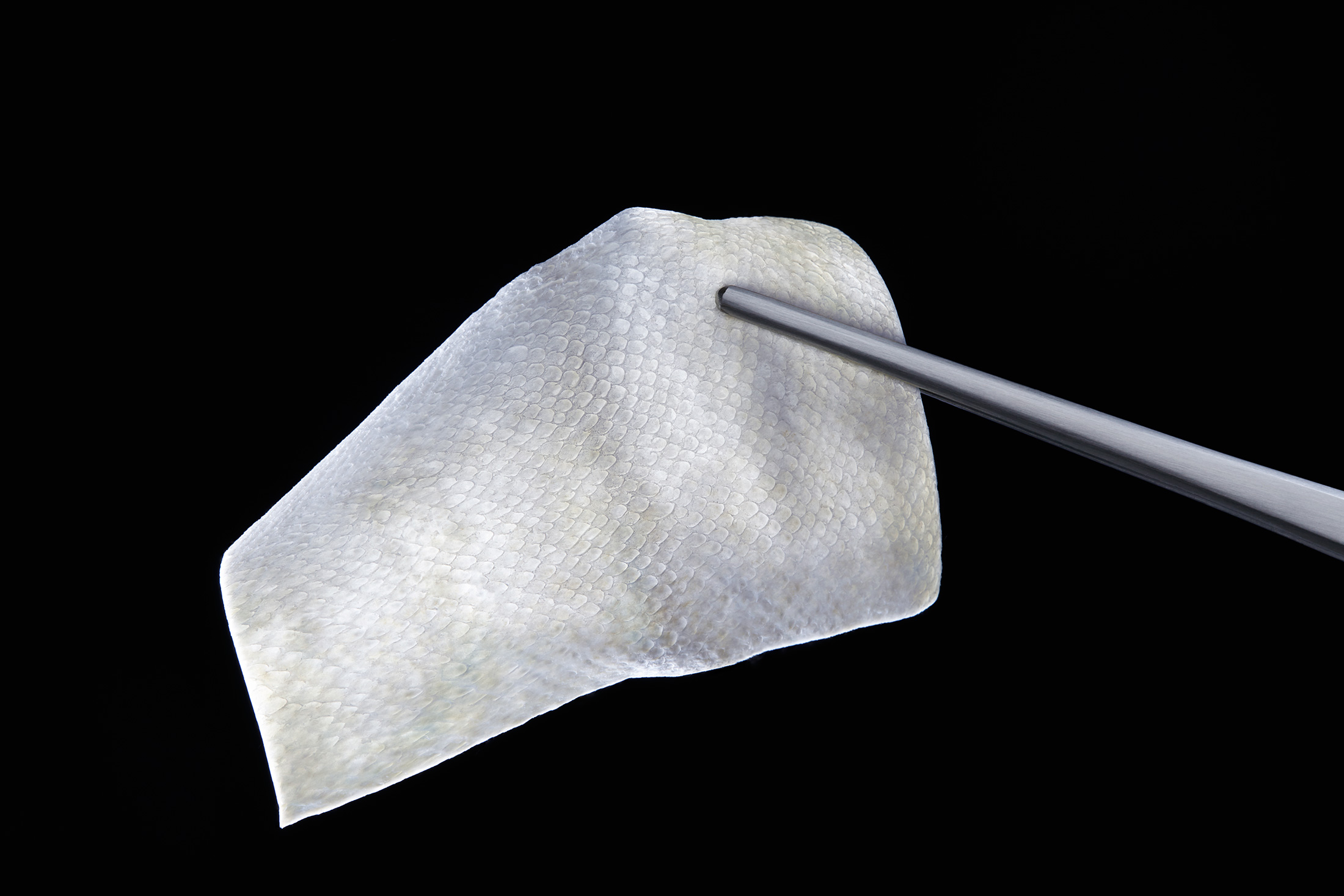

Iceland has a long history of working with fish leather. “My grandfather’s first shoes were the skin of a catfish,” Sigurjonsson says. Instead of kilometers, Icelanders used to mark distance in worn-out fish shoes. Sigurjonsson and his small company have spent the past nine years applying this tradition to the treatment of chronic wounds, those that take longer than a month to heal.