Surgeons in Cambridge are hailing as a success the first heart transplant operation in Europe to use a non-beating heart.

Medical teams at Papworth Hospital spent more than a decade working on procedures to enable the landmark operation before performing the transplant earlier this month.

Doctors said the recipient, Huseyin Ulucan, 60, from London, had made a remarkable recovery, after spending only four days in the hospital’s critical care unit. Ulucan, who suffered a heart attack in 2008, is now recovering well at home.

“This is a phenomenal achievement,” Simon Messer, cardiothoracic transplant registrar at the hospital, told the Guardian. “People who previously would not get a heart transplant will now be able to have them.”

Led by consultant surgeon Stephen Large, the work means that far more hearts can potentially be used to save patients’ lives. “The use of this group of donor hearts could increase heart transplantation by up to 25% in the UK alone,” he said.

Until now, hearts used in transplant operations have come from donors who are declared brain-stem dead, but still have blood pumping around their bodies. For the latest operation, surgeons took a heart from a donor whose heart had stopped beating, in what is termed circulatory death.

The breakthrough involved the use of new techniques to restart the unbeating heart inside the donor minutes after death, and then monitor its function to ensure it was in good enough condition to transplant.

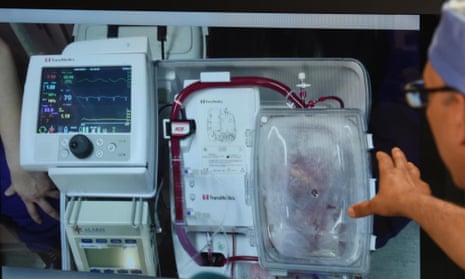

Doctors used ultrasound to assess the function of the restarted heart for 50 minutes before approving it for transplantation. They then removed it from the donor, placed it in an “organ care system”, also known as a heart-in-a-box machine, which perfused the organ with blood and nutrients and kept it beating for three hours until the operation went ahead.

Before the heart transplant, Ulucan could hardly walk. Now, he can make his own way to appointments at the hospital without any trouble. Stephen Petit, a cardiologist at the hospital, told the BBC he expected Ulucan’s quality of life to continue to improve in “leaps and bounds”.

“Before the surgery, I could barely walk and I got out of breath very easily, I really had no quality of life,” Ulucan told the BBC.

More than 250 patients in Britain are on the waiting list for heart transplants, and around 900,000 people in the UK are living with heart failure, according to the British Heart Foundation.

“Currently patients can wait over three years for a heart transplant. But less than half of the people on the waiting list will be transplanted. About 13% die while they are waiting, and around 30% are removed from the list, because they become too unwell to have the operation,” Messer said.

Doctors at five other specialist heart transplant centres around the UK are expected to adopt the procedure soon. Last year, doctors in Australia performed the world’s first non-beating heart transplant using similar procedures.

James Neuberger, associate medical director for organ donation and transplantation at NHS Blood and Transplant, said: “Sadly there is a shortage of organs for transplant across the UK and patients die in need of an organ. We hope Papworth’s work and similar work being developed elsewhere will result in more hearts being donated and more patients benefitting from a transplant in the future.

“We are immensely grateful to the donor’s family and we hope they are taking great comfort in knowing that their relative’s organs have saved lives and have also made an important contribution to heart transplantation in the UK. We also shouldn’t forget the donor families who helped pave the way for the hospital’s recent landmark transplantation,” he said.