This article first appeared on the Anything Peaceful blog.

"This book is too dangerous for the general public," the Bavarian State Library's historian told The Washington Post.

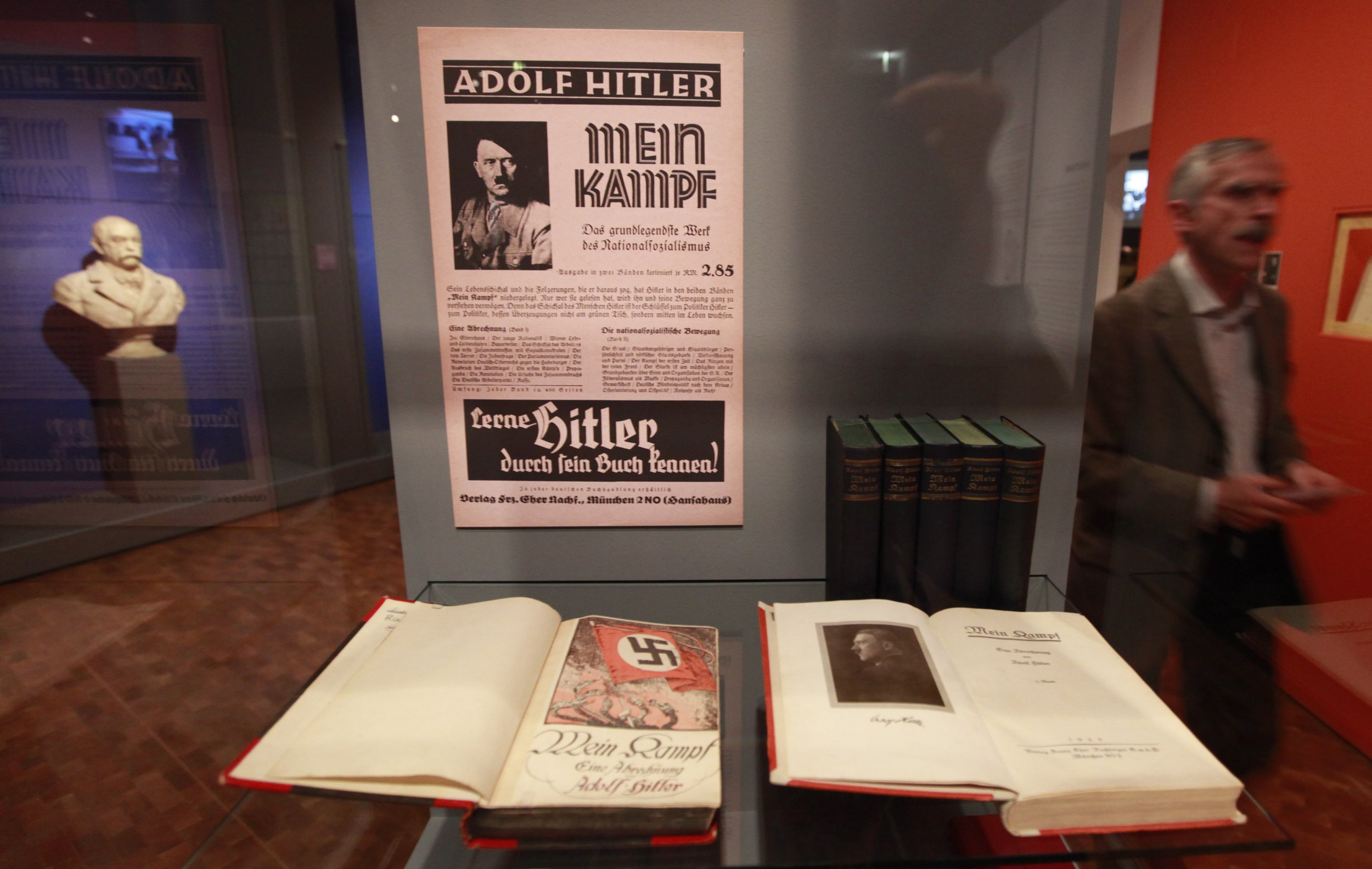

Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf is about to join the ranks of public domain texts as Bavaria's 70-year-old copyright comes to an end in December. Contrary to popular belief, the book was never banned by the German government. Within Germany, the Bavarian state has used intellectual-property law to keep the Nazi manifesto out of the hands of German readers.

Early in 2016, however, Germans will see—and German taxpayers will fund—the first new German edition since Hitler's death, "despite the chorus of opposition," notes the Post, "particularly from Jewish groups and Holocaust survivors."

How can Hitler's apoplectic proclamation—this early and critical link in a causal chain that would ultimately lead to millions of deaths and the suffering of tens of millions more—be once again loosed on the world?

"Decent people can argue that the book is too dangerous to be published," writes philosopher Stephen Hicks. "But the fact is that Mein Kampf is too dangerous not to be published."

Beyond the specifics of the German debate, there is a more important general point about prohibiting even the most repulsive of ideas: Censorship weakens our ability to combat them.

We must understand the "logic" of national socialist beliefs, however dangerously wrong they turn out to be.

Levi Salomon, a spokesman for the Berlin-based Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism, objects: "This book is outside of human logic."

What does this claim mean? Not that Mein Kampf is nonsensical. If it were literally devoid of sense, it would be as harmless as a poem by Lewis Carroll or Edward Lear. The concern here is the opposite: Hitler's book is full of meaning.

Neither can Salomon be saying merely that the Mein Kampf 's logic is faulty and its conclusions invalid. Does he want only objectively correct books to be published?

What he seems to mean by "outside human logic" is something less semantic and more supernatural, like a dark spell that can hold the unwary in thrall to the Führer. Or maybe those who want to censor Mein Kampf think of it as an infection, an ideological virus that can invade the moral cortex and turn the brain to fevered dreams of racial purity.

I'm not suggesting that ideas can't be dangerous. Faulty beliefs are behind the worst dangers humanity continues to face.

But quarantine is not the only way to combat ideological infection. Our immune systems are not strengthened by isolation. When you raise a sheltered kid, you end up with a vulnerable adult. And when the authorities ban dangerous ideas, they produce an ideologically vulnerable population.

Yet you can buy The Communist Manifesto in any college bookstore. Not only have I never heard any anticommunist object to its availability; the majority of Marx's most ardent critics wish that his words were more widely read and far better understood.

Some might argue that the two books are fundamentally different in tone and target, but the only way to know is to read and compare the texts—an exercise that requires both books be available for analysis. Otherwise, we are being told to trust an elite authority whose judgments we cannot check. That would be an ironic prescription for preventing the rise of a Fourth Reich.

"A free society," writes Hicks, "can work only if most of its members understand what principles a free society depends upon and why they are better than the alternatives. That presupposes that they know what the alternatives are."

"There are no short cuts in our ongoing cultural education," Hicks warns. "Every generation must discuss and debate the great ideas—true and false, known and possible, healthy and dangerous—and become intellectually armed so as to defend and advance liberal civilization."

Banning Mein Kampf doesn't make its ideas less attractive to those the censors fear. Neither will exposure to Hitler's maniacal ranting persuade an open-minded reader to embrace illiberality. All it can do is empower the fascists with the cachet of a forbidden text and leave their most likely recruits all the more intellectually vulnerable.

B.K. Marcus is managing editor of the Freeman.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.