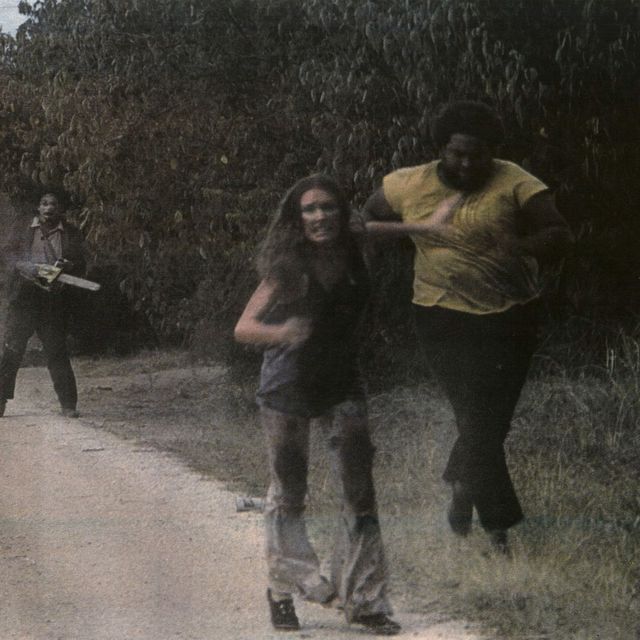

This story originally published on Esquire.com in 2014 as the Texas Chainsaw Massacre passed its 40th anniversary.

Hitting the big 4-0 is a turning point in any man's life, cannibalistic serial killers included. While some men make do with a flashy new sports car or girlfriend to ease the transition, others opt to have a little work done. In the case of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which originally hit theaters on October 1, 1974, writer-director Tobe Hooper has opted for the latter. As the film's special five-disc Blu-ray 40th Anniversary Black Maria Limited Edition made its way into stores via Dark Sky Films, we caught up with Hooper and some of his fellow masters of horror, including Rob Zombie and Alexandre Aja, who revealed some things you might not know about Leatherface and company.

The film is an allegory for the Vietnam War.

For Hooper, the newer, shinier Chainsaw is more than just a piece of moving-picture memorabilia. It's a chance for audiences to revisit the political underpinnings that led to the film's creation in the first place. Though it's easy to think of the film as a straight-up horror movie, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre also belongs to the New Hollywood movement that was happening during the 1970s, an era when films were being influenced by the pervasive disillusionment resulting from events like Watergate and the Vietnam War.

"I was reacting to life around me, as I knew it," says Hooper of the message behind the movie, which proved somewhat prophetic. "The film was, to me, a part of what I felt like we were moving into in the future. An example of that is that in the van the news is on the radio a couple of times and the news has these horrible stories on it about things like an office building in Atlanta collapsing. These things really weren't happening in the '70s, but now they are—and three or four times a day. So it was a reflection of my feelings about the political environment, especially here in Austin, where I had a beard and sandals. It was coming from a part of my reality."

The movie was marketed as a true story. (It's not.)

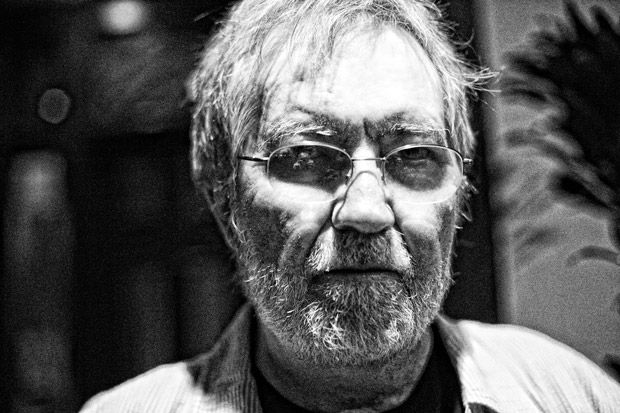

The film's visceral style, coupled with the (false) conceit that it was based on reality, is yet another reason why people are still talking about the film today. "People are absolutely convinced that it did happen," says Gunnar Hansen, who starred as Leatherface and wrote a book in 2013, Chain Saw Confidential, aimed at separating the film's facts from fiction. "Most people are surprised and don't know whether to believe it or not, but there are some who actually get angry when I say, 'No, it didn't happen.'"

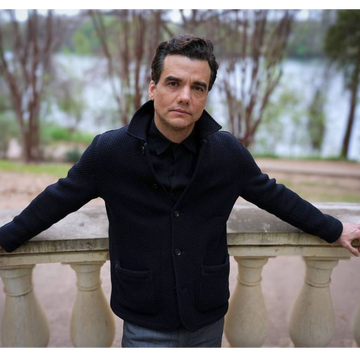

The film's realism is, of course, a major part of its legacy. "Because of Hooper's very realistic tone, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre creates an experience for the viewer that is beyond any other movie—the fact that you absolutely follow the journey of some people into something that is so crude, so violent and brutal, and unflinching," says writer-director Alexandre Aja, whose own horror moviemaking resume includes High Tension, a remake of The Hills Have Eyes, and this month's Horns, starring Daniel Radcliffe. "With maybe the exception of Deliverance and The Last House on the Left, I cannot see any other movie that has that kind of impact on the viewer."

The shoot was excruciating.

The question Hansen is most often asked about the making of the film is: "Was it fun?" His stock answer? "Not a bit of it." That the film was shot in Texas in the middle of summer did not help. "I think it was one side or the other of 100 degrees for almost all of the shooting," Hansen recalls. "And it was Central Texas, which means it was quite humid. For me I think it was also bad because I wore a mask. And that mask was made out of latex. So even though I could breathe through it fine, it was tight up against my skin, so I was always soaking wet under it. And then I had a wool suit and wore wool trousers the whole time."

Hooper doesn't disagree. "My memory of shooting this film is that it was miserable and hot and very hard work," he says with a laugh.

Hooper wasn't afraid to push his actors.

"By the time I finished the film, I think everyone hated me," Hooper says. "Because I knew what I wanted and I knew how to get it."

"It's an odd sort of thing," Hansen says of his relationship with the director. "The first time I saw him years later he actually was clearly nervous that I had walked into the room and he sort of backed away. And I wondered about that because I thought he was really good to work with. I mean he was very demanding in the sense that he had a very clear vision of how he wanted to shoot a scene, but great. He's the kind of director who focused on getting the shot framed, getting the shot lit, and blocking the scene. So he let the actors really be free. It was up to me to create Leatherface. He'd tell me what Leatherface's state of mind was, but he didn't tell me how he wanted me to create that. I think any actor appreciates that, so I had no bad feelings toward Tobe at all."

It's not as gory as you might think.

"One of the most amazing tricks in filmmaking in the [horror] genre is the fact that when you really look at the movie, you realize there is almost no blood or graphic violence onscreen," Aja says. "It's the editing, the rawness, the craziness of what you see that makes the experience so intense. Your mind creates what you don't see in the movie and fills in the gaps to see all the 'massacre' that Hooper doesn't actually show onscreen."

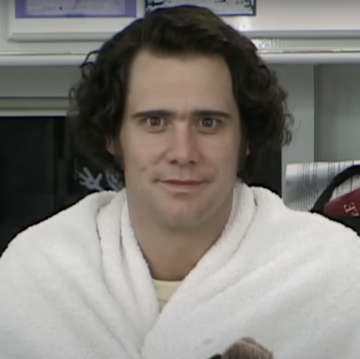

"It's not that bloody, as much as it seems it would be," concurs musician-moviemaker Rob Zombie, who cites the film as a major influence on his own work, including House of 1000 Corpses and The Devil's Rejects. "It's just the style that it was made in. It's beautifully shot—it's that really rough, handheld look. Usually movies look like movies. This just looked like you were there."

Fun fact: Hooper deliberately limited the amount of onscreen violence in (dashed) hopes of getting a PG rating. (The MPAA settled on an "R.")

Leatherface was an entirely new kind of bogeyman.

For his part, Hooper was most interested in using Leatherface to challenge the conventions of the typical horror-movie villain up to that point. "I felt that the real monster was man, not fantasy," he says. "I know the film has this kind of Grimms' fairy-tale archetype that runs through it, but the monster is a man. And you can relate to that more than a monster."

"One thing I really love is that the villains in the movie are so charismatic and so insane," Zombie adds. "Rather than be just these faceless killers who are boring, you're swept up in their own family drama. Between themselves. They're torturing themselves as much as they're torturing their victims. And the actors: You're watching them and going, 'I don't know, are they actors?' They're so convincing and you'd never seen them in anything else that you go, 'I don't know. Maybe that guy's real...' You'd see these movies and it really seemed like they were being made by a maniac. Like the director is going to do anything he can to fuck with your head. You're not safe watching this movie, so beware!"

Final girl Marilyn Burns really was terrified.

In one of the film's final—and most memorable—scenes, Sally (Marilyn Burns) is tied to a chair at Leatherface's dinner table while the family of cannibals taunt and mock her for well over five minutes of screen time. In real life, those five minutes took approximately 26 hours to shoot, according to Hansen. "The whole dinner scene is burned in my memory, I think just because of the misery of it," he says. "At that point we were really just on the verge of mental collapse. And Marilyn told me about how awful it was for her, because she was terrified... Just being tied to a chair and then having these men looming over her constantly, she said it was really unnerving. I think that whole scene was certainly the most intense part of the movie and I think all of us were slightly insane by then."

The movie influenced generations of filmmakers.

Aja still vividly remembers the first time he and his writing and producing partner Gregory Levasseur saw the film. "[We] used to go from video club to video club and empty the shelves of all the horror movies like pirates," says the Paris-born filmmaker. "Because at the time in the early 1990s in France, we couldn't find any great scary movies in the theater. I remember one summer vacation we watched, almost back-to-back, [Wes Craven's] The Last House on the Left and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Those two movies were shocking, unexpected experiences that made a huge impression on us. In particular, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre became one of the most influential movies for me, especially in terms of what I did in the horror genre afterward."

Aja is not alone in his admiration. Hooper's horror opus has been cited as an influence on various filmmakers, films, and television series for four decades now, most recently HBO's True Detective. Wes Craven counts The Texas Chain Saw Massacre among his five favorite movies, describing it as "amazingly visceral visual storytelling." Ridley Scott calls it one of "only a few really, really great [movies]" and used it as a reference for Alien. Rob Zombie's fascination with the film is evident in his entire oeuvre, though at first it was an unconscious impulse.

"When I went to make my first film, House of 1000 Corpses, I didn't consciously think it at the time at all—we were just making the movie—but when I look back on it, I think, 'That is exactly the product of someone obsessed with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And somehow, in his mind, he put them together in a blender,'" Zombie says. "But when I went to make my second film, The Devil's Rejects, it was really the quality of those '70s movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that I was trying to emulate."

Hooper's original 16mm reels were used to restore the film.

Using the same 16mm film reels that actually rolled through Hooper's camera four decades ago, the newly restored film boasts a remastered 7.1 soundtrack and a super-high-resolution 4K transfer that allowed the restoration team to rework the film frame-by-frame, adding color where it was needed and removing scratches, stains, and other visual distractions. Which was no easy task.

"This was easily the most difficult restoration we've ever undertaken, largely due to the condition, history, and nature of the original elements," says archivist-producer Todd Wieneke, who spent nearly a year working on the film's new edition. "Though considered the 'Gone with the Wind of meat movies,' and impeccably directed, photographed, and edited, it is at heart a low-budget, independent, regional film, so the materials weren't always handled with care, particularly in the movie's salad days of distribution. There were innumerable scratches, emulsion digs and tears, splice residue, sprocket tears, dirt and debris, as well as a fair amount of color breathing in the first four reels, which were addressed in the digital restoration."

The 40th anniversary version that played at XSXW is not what showed in theaters.

In March, a refreshed version of the film premiered at SXSW in Austin (which was befitting, considering that is where the film was shot). Hooper was on hand for the screening and thrilled with the audience's response to the film. "They loved it," Hooper told us the day after its premiere. "The response was kind of scary it was so good. It played like a new film. And the audience—which included people who had never seen the film and longtime fans—really seemed to appreciate the nuances that I had put in the film 40 years ago."

Yet even with this unbridled enthusiasm—and a May date with the Directors' Fortnight section of Cannes (where the film had previously screened in 1975)—Hooper wasn't ready to stop tinkering. "Mr. Hooper and I wanted to do some additional restoration and color timing, along with some additional tweaks to the 7.1 audio mix," Wieneke says. Ultimately, work on the film was completed in June, the same month Leatherface made a triumphant return to theaters.

Making the film today would be nearly impossible.

Though many have tried to recapture the dirty magic of Hooper's original, it's all for naught."It would be very hard to do it without executives cramming exposition into it," says Hooper, who also notes that there's nothing he'd change about the film if he were making it today. And he's not surprised that, 40 years later, we're still talking about this little horror film that could. "The films I liked were European films—Fellini, Antonioni, Truffaut—and I didn't see any reason why, if I delivered the fear and the tension, it couldn't be a good motion picture. With characters. Like a painting is a painting. And if it's good, it lasts."