Ocean Park on a hot California morning, the sun already beating down, sprinklers playing across fresh lawns, white buildings rising above parched boulevards that stretch away to the cool waters of Santa Monica bay. I’ve never seen it. Yet it has entered my senses forever because of Richard Diebenkorn.

The abstract paintings of this 20th-century master used to be everywhere, in the form of posters. Luminous overlays of soft, bleached colours balanced on underlying grids that conjured the built-up land against the fathomless Pacific, his Ocean Park paintings were so popular in the 1990s they attracted snobbery.

Abstract art for people who don’t like abstract art, was a common jibe; too easy on the eye, too neat and tidy, was another. When an Ocean Park poster appeared in one of the houses in the Channel 4 soap Brookside, I remember hearing his work compared to downmarket decor.

Perhaps this is one reason why Diebenkorn (1922-93) has been stinted in Britain. It has been so long since the last show – at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1991 – that a generation may never have seen his work. Not the least joy of the Royal Academy’s exhibition is the revelation of scale: the Ocean Park paintings may be amazingly big – nine or 10 square metres – or surprisingly small. Some are painted on cigar box lids.

But more remarkable for British viewers must be the chance to see Diebenkorn’s art evolving over a whole lifetime, from Albuquerque, New Mexico where he studied, to Urbana, Illinois where he taught, Berkeley, California where he lived until 1966, and then Santa Monica and the hundreds of works in the Ocean Park series.

The early abstracts are dense, rich and beautiful – colour and form fitting ruggedly together like outlandish rockeries. Invoking the hot light and open atmosphere of Berkeley in particular, and the wild, red stoniness of Albuquerque, so familiar now from Breaking Bad, they seem to be all about how the eye gets into the terrain, how it sees its way around tall trees, avenues, parks, mountain ranges, buildings and sky. It is no surprise that Diebenkorn was a lifelong student of Cézanne.

Sometimes the early works appear to pivot around a particular form – something like a handprint, a sign or an arrow. These remain mysterious, balancing the arrangements of colour around them. It’s as if something figurative had cropped up in a landscape seen from within, but also from high above; a human detail in the wide south-western landscapes the painter saw from the air while flying back and forth in the 50s between California and New Mexico.

Just as Diebenkorn was finding fame with these intricate yet craggy paintings that hold their marvellous colours – cobalt, forest green, flamingo pink – like the evening sky in the branches of a tree, he suddenly changed tune. Like his near contemporary Philip Guston, he gave up abstraction and turned to the figurative.

This show is perfectly arranged so that you can see this coming almost from the start because the first gallery has sightlines into the second. A doorway frames a terrific painting of a long California street, heavily shadowed by houses in the heat, that spools away into the wild blue yonder. It still has a planar aspect – and some of the real buildings were apparently eliminated to get that patchwork of lawn and field from the early abstracts – but now there are strong hints of Edward Hopper.

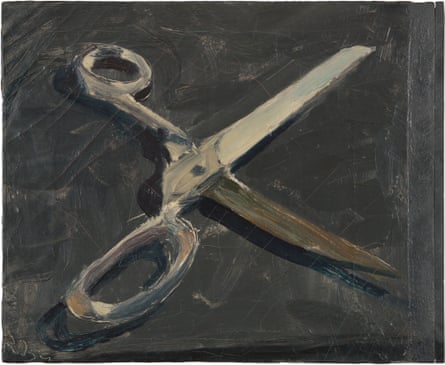

A portrait of a pair of scissors, heavy and old yet still full of iron purpose; a man sitting shirtless and pensive in the dusk; the parched sidewalks of Berkeley – Diebenkorn pays open homage not just to Hopper and Cézanne but now Matisse. He paints his wife, his neighbourhood, the humble objects of his house and studio with a tough, terse brush but a seductive love of the subjects as well as the paint itself.

The burning blue of a Bay Area sky held in balance with the softer greens and blues of the land and sea below are pinned together with the succinct black drawing, so delicate and yet structural, that you see throughout his career. It keeps a rigour to these paintings that might so easily spill over into swoony light and heat. But just as Diebenkorn was becoming the best known of the Bay Area figurative artists, he did the opposite of Guston, turning once more to abstraction.

On a trip to Russia, Diebenkorn had seen Matisse’s great and strange French Window at Collioure, with its haunting planes of darkness and light, and the memory stayed with him. There is a genetic link from the Matisse to everything you see in the last rooms of show: these rectilinear paintings, so gorgeous and yet serious, so hard-won, showing what he called the ‘tension beneath the calm’.

Of course the Ocean Park paintings have beauty and balance as their uppermost characteristics. The California blues are all there – cobalt, aqua, sky, cerulean, the faded jade and turquoise of boatyards, beaches and outdoor pools. And the architectural structure below is so elegant in its measured thinking, in its geometry and even its joinery.

But are they expressive of whole landscapes, could they be evocations of someone’s sprinklered garden with its sparkling pool? How does the atmosphere enter in? The paintings are stranger than expected, and this paradise is not without shadows – sometimes a grey pall, or a funereal black border edging into the frame.

In fact the Ocean Park series that has given so many people such pleasure arrives out of hesitation, correction, uncertainty, further attempts, frequent cancellations. How can one tell? Diebenkorn leaves the workings on show. The veils of colour that settle on the painting like a misty haar lie over many trials and second thoughts. The paintings look light, bright, uplifting, slim; but this only comes after long and patient thinking.

This is what connects late with early; all of these paintings are bent on seeing and depicting the same thing – cities and landscapes – in new ways. The elements may be the same, the architecture of lines and planes, the suave black drawing, the patches, clusters and veils of atmospheric colour. But the sense of endeavour, of tension, scrutiny and indecision changes every time and makes each painting vital and restless for all its composure. Even at the end, Diebenkorn is still trying to work out another way to give us the light and space of California.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion