What Flannery O'Connor Got Right: Epiphanies Aren't Permanent

Author Jim Shepard's favorite passage from "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" highlights a sad truth: A moment of clarity only lasts a moment.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature.

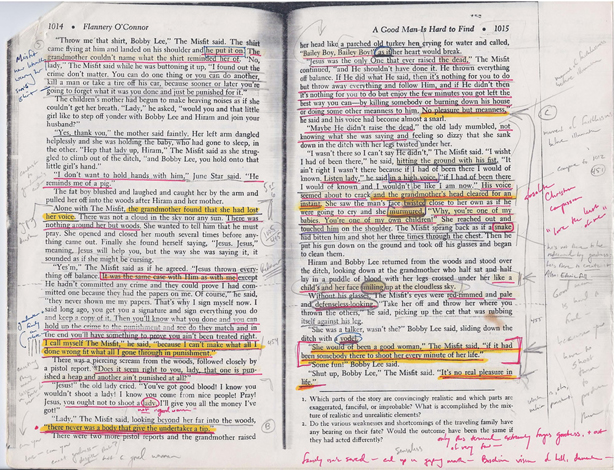

Flannery O'Connor's classic short story "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" moves from satiric family comedy to brutal revelation as a grandmother leads her exasperated family on a wild goose chase in rural Georgia. While looking for the site of her girlhood homestead, she inadvertently brings her whole family to their deaths at the hands of a tortured killer, The Misfit. He displays an odd regard for the grandmother, who forgives him right before she dies:

"She could have been a good woman," The Misfit said, "if it had been someone there to shoot her every minute of her life."

For Jim Shepard, author of Love and Hydrogen and You Call That Bad, this line has been cause to contemplate what it means to be good—and the value of goodness when it's merely fleeting. If human beings can muster startling flashes of selflessness and generosity, why do we revert so quickly to our flawed, limited selves? And does the fact that we do relapse into old patterns diminish what we are in our best moments? O'Connor's story helps Shepard wrestle with these questions as he crafts his own imperfect characters, who catch glimpses of how to become better—but are often not quite strong enough to change.

When I first encountered "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," I read it the way many people do when they first encounter the story—a kind of social satire that veers over into random violence, plus a little spasm of hard-to-sort-through theology at the end. But when you spend more time with it, it becomes clear the story is a hugely powerful acting-out of a theme O'Connor said was crucial to her work: the action of grace in territory held largely by the devil.

Writers talk a lot about epiphanies—what O'Connor, in her Catholic tradition, called "grace"—in short stories. But I think we're tyrannized by a misunderstanding of Joyce's notion of the epiphany. That stories should toodle on their little track toward a moment where the characters understand something they didn't understand before—and, at that moment, they're transformed into better people.

You know: Suddenly Billy understood that his grandmother had always gone through a lot of difficult things, and he resolved he would never treat her that way again.

This kind of conversion notion is based on a very comforting idea—that if only we had sufficient information, we wouldn't act badly. And that's one of the great things about what The Misfit tells the Grandmother in the line I like so much. He's not saying that a near-death experience would have turned her into a good woman. He's saying it would take somebody threatening to shoot her every minute of her life.

In other words, these conversion experiences don't stick—or they don't stick for very long. Human beings have to be re-educated over and over and over again as we swim upstream against our own irrationalities.

(There's a great line in Orson Welles' film Citizen Kane, where one of the protagonist's enemies says to him: "You're going to need more than one lesson, Mr. Kane, and you're going to get more than one lesson.")

Now, O'Connor really believes that we can flood, momentarily, with the kind of grace that epiphany is supposed to represent. But I think she also believes that we're essentially sinners. She's saying: Don't think for a moment that because you've had a brief instant of illumination, and you suddenly see yourself with clarity, that you're not going to transgress two days down the road.

I find this idea enormously useful in my own work. My characters are all about gaining an understanding of the right thing to do—and avoiding it anyway. That sense that we can be in some ways geniuses of our own self-destruction runs, in some ways, counter to the more traditional notion of the epiphany—which tells us that stories are all about providing information to characters who badly need it. Epiphanies are, in some ways, staged and underimportant.

But you still don't want to write them off. The fact that there's a brevity to human connection and human empathy—the fact that it goes away—might make you feel that we should not make a big deal that it was there at all. But of course we can't do that. We have to value the moments when a person is everything we'd hope this person would be, or became briefly something even better than she normally is. We need to give those moments the credit they're due. The glimpse of this capacity is part of what allows you to write characters who are so deeply flawed. Given that so much great literature is about staggering transgression, knowing that that capability of striving for something better is crucial for keeping you reading.

O'Connor's view of humanity in these stories is that almost everybody's going to be found wanting much of the time. And we are. But you still want to cherish those moments when someone shows you they have the capacity to be better.