According to a seminal 2015 report on diagnostic errors1 by the Institute of Medicine,

“It is likely that most of us will experience at least one diagnostic error in our lifetime, sometimes with devastating consequences.”

Indeed, studies on diagnostic error in the U.S. have suggested overall misdiagnosis rates from 5%2 to 15%3 and as high as 97% for certain diseases like Celiac Disease4.

Misdiagnosis results in poor patient outcomes and excessive healthcare costs. A Johns Hopkins study5 concluded that it is also the single largest cause of medical malpractice lawsuits, accounting for 35.2% of payouts and an estimated 80,000 to 160,000 potentially avoidable deaths and significant permanent injuries each year.

The misdiagnoses stem from delays or failure to treat an underlying disease or from treating diseases that are not actually present. That would make diagnostic errors the third leading cause of death6 in the U.S. after heart disease and cancer. A study published in BMJ reports that approximately half of all diagnostic errors7 with adult outpatients are potentially harmful.

Telemedicine and COVID-19 Impact

Potentially exacerbating the diagnostic error rate is the growth in telemedicine over the last decade. The use of telemedicine has increased by 50-175x8 during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a McKinsey study.

On the one hand, telemedicine may increase accessibility, thereby enabling earlier diagnoses that can result in better patient outcomes. On the other hand, what happens when a physician cannot perform the full physical examination on a patient via phone or video chat that could be done in the clinic? Will important clues be missed when relying largely on a patient’s descriptions of her symptoms?

Not surprisingly, The Doctors Company, a leading malpractice carrier, reports9 that diagnostic error is the most common allegation10 in telemedicine-related claims against their members. The top telemedicine misdiagnoses include:

- cancer (25%),

- stroke (20%),

- infection (20%)

- orthopedic concerns (10%).

Historically, telemedicine-related claims have been a small component of claims.

But the McKinsey study reports that 76% of consumers want to use telemedicine going forward, up from 11% actual usage in 2019. And 57% of providers view telehealth more favorably than they did before COVID-19. So, we can expect telehealth to be an even more significant component of patient encounters in the future—and diagnostic error rates to potentially grow if the right precautions aren’t followed.

COVID-19 likely impacts diagnostic error rates in other ways:

- The disease itself can express in a multitude of symptoms, complicating diagnoses.

- Clinical staff is stretched during outbreak surges, potentially leading to cognitive fatigue.

- Quickly introduced provider organizational processes to address the surge while promoting staff and patient safety could make clinicians more error-prone.

An Inconvenient Truth

If diagnostic errors are such a big deal, why don’t we hear more about it?

“Overall, diagnostic errors have been underappreciated and under-recognized because they’re difficult to measure and keep track of owing to the frequent gap between the time the error occurs and when it’s detected,” says Dr. David Newman-Toker, leader of the Johns Hopkins study.

“These are frequent problems that have played second fiddle to medical and surgical errors, which are evident more immediately.”

Indeed, accurate data on diagnostic error rates are exceedingly hard to come by, so no one knows for sure. Even the definition of diagnostic error has been the subject of much discussion amongst those who follow the topic. Nevertheless, physicians I’ve spoken with agree that it is much more common than the public realizes.

Reluctance to report

In addition, Newman-Toker suggests that experts have downplayed the scope of diagnostic errors because they are afraid to open a can of worms they can’t close. He says, “Progress has been made confronting other types of patient harm, but there’s probably not going to be a magic-bullet solution for diagnostic errors because they are more complex and diverse than other patient safety issues.”

It should also be noted that traditionally, physicians and other clinicians have been reluctant to report their colleagues’ diagnostic errors when noticed due to a culture of mutual support.

They’ve also been reluctant to self-report mistakes in fear of malpractice liability. Similarly, hospitals and other provider organizations have an incentive to protect their reputation and finances by not drawing attention to diagnostic errors. It’s also natural to believe that while such errors may be more common than generally appreciated, the problem lies with others.

What is diagnostic error?

Diagnostic error can be thought of as a failure to accurately identify and communicate on a timely basis the cause of a patient’s health problems. Not surprisingly, effective treatment plans—from both patient outcome and cost perspectives—depend largely on accurate and timely diagnoses.

The Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine11 suggests that there are three subcategories of diagnostic error:

1. Wrong diagnosis

An example would be when a patient who is having a heart attack is diagnosed as having acid indigestion. The accurate diagnosis may be identified from a post-mortem study. This, of course, isn’t always done. And when it is, the data isn’t necessarily flagged and reported as a diagnostic error, making actual data hard to quantify.

2. Delayed diagnosis

The most common is cancer. If it isn’t detected early, it usually becomes much harder to treat. However, many illnesses aren’t suspected until symptoms persist or worsen.

3. Missed diagnosis

Sometimes the causes of patients’ complaints are simply not identified. Examples might include chronic headaches or fatigue or loss of appetite.

Why do we have so many diagnostic errors?

The causes of diagnostic error are many. They can be attributed to cognitive issues driven by the complexity of diagnosis and to system issues driven by the way healthcare is delivered.

With almost 70,000 diseases12 represented by ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes, but less than 200 presenting symptoms,13 it is impossible for any physician to know about every disease and its associated signs and symptoms. Even with clinical decision support tools and access to expert databases, getting to the right diagnosis requires a strong foundation in the diagnostic reasoning process. This is what many would describe as the “Sherlock Holmes part of medicine.”

It’s critical to understand why one would ask certain patient history questions, conduct certain physical exams, consider certain diseases (“differential diagnoses”), and order certain tests from thousands available to efficiently evaluate the most likely or most harmful diagnoses. Of course, one must accurately interpret those findings to get to the right diagnosis so the right treatment can be provided.

Related Content:

Diagnostic Error: A Missed Opportunity to Improve Patient Safety?

The Why and How of Diagnostic Errors

-To err is human

To err is human, and the potential for cognitive error is significant when time and cost pressures make it difficult to be as comprehensive as one would like. A physician may resort to pattern matching. Perhaps he saw this combination of symptoms in a patient recently and quickly concludes it is, therefore the same disease. While efficient in time, the diagnosis may, in fact, not be the same.

He must therefore know when it’s critical to investigate other possibilities. Or he may have failed to ask questions, conduct physical exams or order tests that might have been pivotal in narrowing the differential diagnoses. Adding to the challenge, the patient may not have accurately described her symptoms. Any of these issues can lead to premature—and incorrect—closure.

Less experienced physicians may exclude an important hypothesis simply because the patient doesn’t exhibit all the classic symptoms. Yet patients seldom exhibit all “classic” signs and symptoms. Learning time and cost naturally limit the variety of patient encounters and presentations during apprenticeship training and residency.

-Lack of feedback

Unfortunately, providers rarely get feedback if a diagnosis was incorrect or changed. There are no standardized measures of diagnostic accuracy that are reported back to them.

Usage of the non-forensic autopsy, the gold standard in identifying diagnostic errors, has dropped dramatically since the 1950s.14 In 1970, JCAHO eliminated minimum autopsy rates as an accreditation requirement. In 1986, Medicare stopped paying for autopsies. Not surprisingly, by 2005, they were performed in less than 10% of all hospital deaths, with far lower rates at non-academic institutions, if at all.

–System infrastructure

System infrastructure and process issues also contribute to the problem. Critical diagnostic tests must be available and affordable. Data must be accurate, and results must be communicated on a timely basis. Operational, communications, or collaboration breakdowns might get in the way, especially when patients are transferred between facilities, physicians, or departments. Specialists must be available when consultations are necessary.

♦♦Love Our Content?♦♦

Sign up for our Newsletter Here

As clinician shortages and value-based reimbursement put pressure on the length of time available for appointments, adequate patient-provider face time for the critical patient history and physical exam becomes increasingly difficult to obtain. Inadequacies in these areas are present in 56% and 47% of missed diagnoses,15 respectively.

While electronic medical records provide an important repository of information that makes collaboration and follow-up more effective, the data entry and other paperwork, which can take 50% of a physician’s time,16 makes it even harder to get adequate patient-provider face time.

While any one of the cognitive or systems issues can lead to diagnostic error, research17 has shown that oftentimes multiple issues come into play.

Outlook

The first step in addressing any problem is to acknowledge that the problem exists. While it has been difficult to accurately quantify the scope of our nation’s diagnostic error rate, there is growing recognition that it is a large issue that must be dealt with. Patient safety, of course, is paramount. And it is core to the Hippocratic oath.

Leading researchers on diagnostic accuracy like Dr. David Newman-Toker of Johns Hopkins, Dr. Hardeep Singh of Houston Veterans Affairs Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Dr. Mark Graber, former President of the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine, and many others have long reported on the estimated magnitude and causes of diagnostic error. The Institute of Medicine report was an important validation of their work and has brought even greater national attention to the issue.

-Policies to support effective diagnosis

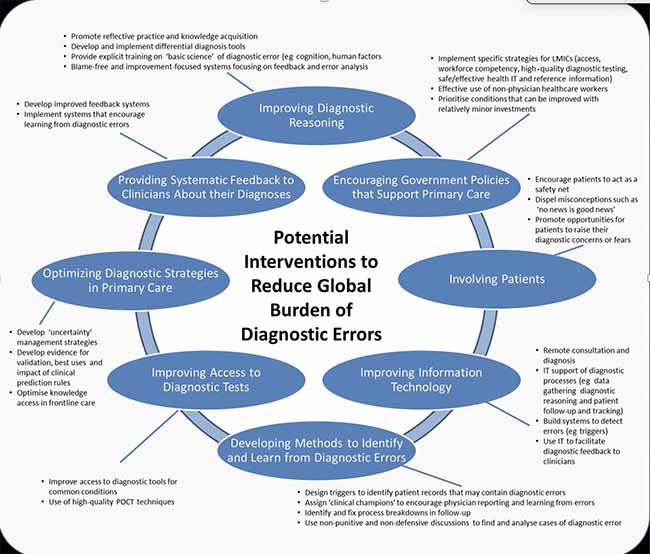

A paper on the global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care18 by Dr. Singh et al. identifies eight potential interventions to reduce such errors. These range from improving diagnostic reasoning, information technology, and access to diagnostic tests to involving patients, optimizing diagnostic strategies, developing ways to identify and learn from diagnostic errors, and providing systemic diagnostic feedback to clinicians. In addition, the authors recommend government policies that specifically support effective diagnosis at the primary care level (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Potential interventions to reduce the global burden of diagnostic errors. IT, information technology; POCT, point-of-care testing (Graphic has (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

-Mitigation strategies

To reduce the risk of diagnostic error in the COVID-19 era,19 Drs. Tejal Gandhi and Hardeep Singh recommend mitigation strategies using the Safer DX framework. This framework uses technology and other systems-based approaches to reducing diagnostic error:

- Electronic decision support systems to assist clinicians in interpreting tests

- Technology-facilitated safety practices, including outreach to patients who have missed appointments to prevent delays in evaluation and diagnosis as well as triage protocols and follow-up systems to optimize telemedicine

- Changes to workflow and communication to support comprehensive discussions with patients about symptoms and concerns, and physician buddy systems for clinicians working in unfamiliar areas

- People-focused interventions such as multi-clinician “diagnostic huddles” for challenging cases, and tools for patient self-triage and awareness of when to seek medical attention

- Provider organizational strategies to ensure a strong safety culture in which staff feel free to ask for help or express concerns, get support as needed, and are less likely to have the fatigue, stress, and anxiety that can impair cognitive function

- State/federal policies and regulations, including guidelines on standardized diagnostic performance and outcomes metrics

Yet, a 2019 review of 26 studies20 that recommended strategies to reduce diagnostic errors revealed limited evidence on interventions being practically used. Knowing what to do may be necessary, but not sufficient, to improving diagnostic accuracy given its complex issues.

-Shift to value-based reimbursement

Perhaps the greatest catalyst for addressing diagnostic error on a broad scale will be the rapid shift in healthcare from a volume-driven fee-for-service reimbursement system to outcomes and a cost-effectiveness-driven value-based reimbursement system. With this new payment environment, diagnostic error rates will directly impact provider revenue and financial stability.

No provider organization wants to waste money on treating the wrong disease while the real disease escalates to the point where it is much costlier to deal with, or the patient dies—both of which are bad under value-based reimbursement. And provider organizations are looking at ways to leverage more nurse practitioners and physician assistants, who may be more available and less expensive than physicians. But they also have less training.

Thus, health systems are getting serious about diagnostic accuracy. They experiment with real-time clinical decision support tools and artificial intelligence systems that prompt the clinician to consider certain diagnoses. And they make sure that they utilize advances in broadly scalable online simulation technology to evaluate their new and experienced clinical staff on diagnostic reasoning and to remediate or provide continuing education as appropriate.

References

- Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. The National Academies Express. Consensus Study Report 2015 https://www.nap.edu/catalog/21794/improving-diagnosis-in-health-care

- Hardeep Singh,1 Ashley N D Meyer,1 Eric J Thomas2. The frequency of diagnostic errors

in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations, Open Access, BMJ Quality & Safety Online First, published on 5 May 2014 as 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627 - Mark L. Graber, MDNancy Franklin, PhDRuthanna Gordon, PhD. Diagnostic Error in Internal Medicine, JAMA

- Alex Dunbar. Celiac Disease is misdiagnosed in 97% of all cases despite growing awareness, CNY Central. Feb 2012. https://cnycentral.com/news/local/celiac-disease-is-misdiagnosed-in-97-of-all-cases-despite-growing-awareness

-

Diagnostic Errors More Common, Costly And Harmful Than Treatment Mistakes. John Hopkins Medicine, Apr 2013. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/diagnostic_errors_more_common_costly_and_harmful_than_treatment_mistakes

-

Leading Causes of Death, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Source: Mortality in the United State, 2019, data table for figure 2. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

- Hardeep Singh, Ashley N D Meyer, Eric J Thomas. The frequency of diagnostic errors

in outpatient care: estimations from three large observational studies involving US adult populations. BMJ Quality & Safety Online First, published on 5 May 2014 as 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002627 https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/qhc/early/2014/05/05/bmjqs-2013-002627.full.pdf -

- David L. Feldman, MD, MBA, FACS. How COVID-19 Accelerated Telemedicine Use, The Doctor Company, Updated May 2020 https://www.thedoctors.com/articles/how-covid-19-accelerated-telemedicine-use/

-

David L. Feldman, MD, MBA, FACS. How COVID-19 Accelerated Telemedicine Use, The Doctor Company, Updated May 2020 https://www.thedoctors.com/articles/how-covid-19-accelerated-telemedicine-use/

-

What is Diagnostic Error? Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine. https://www.improvediagnosis.org/what-is-diagnostic-error/

-

International Classification of Diseases, (ICD-10-CM/PCS) Transition – Background. CDC, National Center or Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm_pcs_background.htm

- List of medical symptoms, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_medical_symptoms

- Kaveh G. Shojania, M.D., and Elizabeth C. Burton, M.D.

The Vanishing Nonforensic Autopsy, The New England Journal of Medicine. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:873-875

- Hardeep Singh, MD, MPHTraber Davis Giardina, MA, MSW, et al. Types and Origins of Diagnostic Errors in Primary Care Settings, May 2013

- Kelly Young – Edited by David G. Fairchild, MD, MPH. Half of Physician Time Spent on EHRs and Paperwork, NEJM Journal Watch. Sep 2016

- Mark L. Graber, MDNancy Franklin, Ph.D.Ruthanna Gordon, Ph.D. Diagnostic Error in Internal Medicine, JAMA Internal Medicine

- Hardeep Singh, Gordon D Schiff, Mark L Graber Quality & Safety, The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care Vol 26, Issue 6 https://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/26/6/484

- Tejal K Gandhi, MD, MPH, Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH. Reducing the Risk of Diagnostic Error in the COVID-19 Era, Journal of Hospital Medicine, J. Hosp. Med. 2020 June;15(6):363-366.

Originally published February 19, 2017. Updated April 6, 2021.

Norm Wu

Norm Wu is the former CEO of i-Human Patients, Inc., a healthcare IT company (now part of Kaplan, Inc.) that provides comprehensive virtual patients for assessing and developing critical diagnostic reasoning competencies in healthcare profession students and practitioners.

He is a serial entrepreneur, having founded four prior technology and healthcare start-ups, including direct primary care pioneer Qliance, where he was the founding CEO. Although he is now retired, he continues to serve on the Advisory Boards of multiple health care and health tech startups.

Prior to becoming an entrepreneur, Norm spent ten years at Bain & Company, where as Vice President, he oversaw half of their global high technology practice and led relationships with four different health system clients. He earned his BS and MS degrees in electrical engineering from Stanford, and his MBA from Harvard.

Comments:

Leave a Reply

Comment will held for moderation

Hello Norm, that summarizes my point: it shouldn’t be left up to a health system’s “economic self-interest” to determine if a public safety issue like diagnostic errors should be addressed or not.

I was involved in the Institute of Medicine’s report (but only peripherally, as a patient interviewed about being misdiagnosed with GERD during a heart attack, for a short film shown during the 2015 launch of the report called “Improving Diagnosis in Healthcare”. https://myheartsisters.org/2015/09/27/mandatory-reporting-of-diagnostic-errors-not-the-right-time/

At least twice during this report launch briefing that I watched live on my laptop screen at the time, I was dismayed and shocked to hear this feeble excuse voiced by the IOM committee chair in response to media questions:

“Now is not the right time for mandatory reporting of diagnostic errors.”

But if “now” is not the right time for mandatory reporting, when might that right time be?

Instead, the chair declared that “voluntary reporting efforts should be encouraged and evaluated for their effectiveness.” But the truth, of course, is that nothing is going to change, ever, until we see mandatory reporting of diagnostic error.

We can all see pretty clearly how all of this “voluntary reporting” is working out in medicine, compared to every other sector focused on issues of public safety. As I later wrote: ( https://myheartsisters.org/2015/09/27/mandatory-reporting-of-diagnostic-errors-not-the-right-time/ )

“That shift towards mandatory reporting when bad things happen in order to protect public safety explains why we no longer have voluntary hard hat usage on construction sites, or voluntary speed limit laws on our highways, or voluntary safety checklists by airline pilots before takeoff.”

No matter how much we’d like to believe that “health systems are getting serious about diagnostic accuracy”, that belief is meaningless without requiring mandatory reporting of errors. As ProPublica journalist Marshall Allen told a Stanford University audience at Medicine X:

“Until you start measuring something, you can’t improve it.”

Carolyn, I believe that people respect what you inspect. Thus, if laws are changed to require mandatory reporting of diagnostic errors, I think we’d see a lot more attention given to reducing such errors.

However, given my experience working in the past on healthcare legislation and the varied interests of different stakeholder groups, I suspect that getting laws (or even CMS regulations) passed to require such mandatory reporting would require hard data on efficacy as well as input from different stakeholder groups as to what data is collected, how that is presented and interpreted, etc. That would take some time and would thus be frustrating for many. Ideally, one or more institutions that have taken this seriously will be able to demonstrate that tracking diagnostic error and addressing its causes has resulted in improved accuracy, improved patient outcomes, and cost savings – in a way that brings in different stakeholders as part of the solution, not part of the problem. Our government can help by funding efficacy research in this area.

I believe that in the absence of mandatory reporting near-term, if health systems find it in their economic self-interest to track and address diagnostic error, they will do so. I’m hopeful that the shift towards value-based reimbursement in healthcare will provide such a catalyst to do so…and that evolving technologies will make it easier to address the issue.