This piece is part of Future Tense, a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University. On Thursday, Oct. 2, Future Tense will host an event in Washington, D.C., on science fiction and public policy, inspired by the new anthology Hieroglyph: Stories & Visions for a Better Future. For more information on the event, visit the New America website; for more on Hieroglyph project, visit the website of ASU’s Project Hieroglyph.

Sci-fi writer Neal Stephenson is worried about America. “We have lost our ability to get things done,” he wrote in 2011, in a piece for the World Policy Institute. “We’re suffering from a kind of ‘innovation starvation.’ ” And part of the problem, he wrote, is science fiction. Where science fiction authors once dreamt of epic steps forward for humanity, now, “the techno-optimism of the Golden Age of SF has given way to fiction written in a generally darker, more skeptical and ambiguous tone.”

Others have picked up where Stephenson left off. In an op-ed for Wired titled “Stop Writing Dystopian Sci-Fi—It’s Making Us All Fear Technology,” Michael Solana wrote, “Mankind is now destroyed with clockwork regularity. … We have plague and we have zombies and we have zombie plague.”

Well, Stephenson wants to do something about that. He’s urged science-fiction writers to help reignite innovation in science, technology, and how they’re used, and his mission helped create Hieroglyph, a new anthology of optimistic, aspirational science-fiction stories. The collection includes stories from Stephenson himself and some of the best science fiction writers in the business, several of whom also happen to be my friends. The thesis behind Hieroglyph, that one of the roles of science fiction is to dream bigger, to help us imagine positive outcomes for society—is one that I fundamentally agree with.

But in our enthusiasm for aspirational science fiction, let’s not be so quick to dismiss the importance of dystopias.

Right now, the landscape of dystopias may be dominated by zombie tales and young adult novels with teen protagonists facing barely plausible totalitarian regimes. Yet there’s a deeper tradition in science fiction of warning tales that have influenced our society—in positive ways—just as much as aspirational stories have.

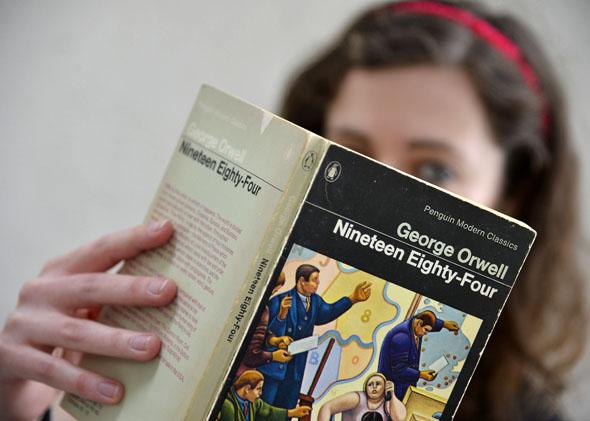

Who doesn’t know the broad outlines of George Orwell’s 1984? Whether or not you’ve read the book, whether you’ve seen either of the film adaptations of the book, you know that it deals with state surveillance and state control of the media.

Orwell wasn’t right about where society was in 1984. We haven’t turned into that sort of surveillance society. But that may be, at least in small part, because of his book. The notion that ubiquitous surveillance and state manipulation of the media is evil is deeply engrained in us. And certainly, the geeks who make up the bulk of the computer and Web industry have largely absorbed that meme, and that’s part of the reason they tend to angrily push back on things like NSA surveillance when it’s uncovered.

1984 may be an example of a self-defeating prophecy. It was David Brin, one of the Hieroglyph authors, who first introduced me to the idea that a sufficiently powerful dystopia may influence society strongly enough to head off (or at least help head off) the world that it depicts. That alone is a compelling reason for society to create smart dystopias.

Other important dystopias are scattered throughout science fiction’s past and its present.

Brave New World dealt with a kind of proto-genetic engineering of the unborn, through really, as many dystopias do, it dealt with totalitarianism. The 1997 film Gattaca updated Brave New World, bringing us to a future where genetic testing determined your job, your wealth, your status in life. And here I have a confession to make. I absolutely hated Gattaca. I left the theater shaking my head because the science in the film was just terrible. No genetic test will ever tell you how many heartbeats you have left. No genetic test will ever be more accurate in telling an employer how well you’ll do at a job than your performance at a past job would be. The film was a gross exaggeration.

Why do I bring Gattaca up, then? Because it was effective. Genetic discrimination on the scale and pervasiveness that Gattaca depicted may have been an exaggeration, but there was a real risk that employers might discriminate against the unlucky carriers of particular genes, and the very high likelihood that insurance companies would raise rates or drop coverage for people who carried certain disease genes. But in 2008, heading off a Gattaca-esque future, Congress passed GINA, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, which makes it illegal for employers or health insurers to base their decisions on your genes. And Gattaca, a film seen by millions, if not tens of millions, helped lay the groundwork for GINA.

Dystopian fiction has also helped us pass down important mores about the freedoms we find central, and helped rally people against injustice.

Fahrenheit 451 dealt with the fear of state censorship. That may seem quaint now, but consider its historical context: Written in an era of McCarthyism, the House Un-American Activities Committee, and blacklisting of anyone believed to have Communist sympathies, Ray Bradbury’s incendiary dystopia wasn’t really about the future—it was about the present he lived in. (And, ironically, Fahrenheit 451 has been censored or banned on at least three different occasions inside the United States since it was published.)

What of our present? We have our own share of warning tales, and for my money, they’re among the most important pieces of science fiction being written. Pick up Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother and Homeland and you find a warning tale, not of the far future, but of the barely-future, a warning about state surveillance, about overreach in the name of the War on Terror, about the abrogation of civil liberties, about the loss of privacy.

Or read Paolo Bacigalupi’s Hugo- and Nebula-Award-winning The Windup Girl, a warning about climate change, the end of fossil fuels, corporate control of food, and corporate control of people.

These are powerful books, with powerful messages, about futures we want to avoid, some near, and some far. These are books I expect to last the test of time. More than that: We need these books. We need people being shaken out of complacency on real threats to society, just as much as we need them being inspired by compelling new possibilities for society. (Cory Doctorow, by the way, is another writer with a story in Hieroglyph, demonstrating that the very same writers can pen both warning tales and optimistic stories. Indeed, many warning tales, including Doctorow’s, can also be inspirational and optimistic in the ways in which characters persevere or overcome.)

I’m an optimist. My own fiction, while it has its own dark warnings about pitfalls ahead, depicts the potential of science to improve society by networking human minds. More broadly, when I look at the world around us, I see that we’ve made it tremendously better over the ages, perhaps two steps forward, one step back, but better nonetheless. I expect the future to be brighter, not darker.

Yet if that’s to happen, it will happen both because we have pole stars to aim for—the aspirational science fiction dreams that Neal Stephenson wants to bring more of into the world, and for which I applaud him—and because we have compelling warning tales that inform us of the pitfalls we need to avoid.

So by all means, pick up a copy of Hieroglyph. I have, and I’m loving it so far. And at the same time, let’s keep those smart, thoughtful, prescient dystopias coming as well. The world needs both sides of that coin.