ANAPRA

It doesn’t look like the most dangerous place on earth. It looks like somewhere half-made, it looks like an aborted thought. It looks like a three-year-old god threw together some cardboard boxes and empty coffee tins and Coke bottles in the sandpit of the Chihuahuan desert, and then forgot it. Left it to its own vices. The god was forgetful and has not returned to care for his creation, but other gods, pitiless ones, are approaching even now, in a speeding pick-up truck.

There’s no more than a hurried moment to look around this careworn land. A dozen of the roads are paved: cracked concrete and full of holes; the rest are just rutted strips of dirt. Most of the houses aren’t houses at all, but jacales: shacks made of packing crates and sheets of corrugated iron, of cardboard and of crap, with roofs of plastic sheeting or tar paper held down with old car tyres. The best have cinder block walls. The worst take more effort to imagine than is comfortable. Few have running water. One or two have stolen electricity using hook-ups from the power lines, a dangerous trick in a world made of sun-baked cardboard and wood.

The jacales are things that might, some distant day, be the ghostly ancestors of actual houses. When those houses are finally built they will be built on lines of hope – the grid that’s already been optimistically scratched far out into the desert in the belief that this place can become a thriving community. Already, there are attempts to make this a normal kind of place: whitewashed breezeblock houses with green tin roofs, the Pemex gas station, a primary school, a secondary school. There’s even the new hospital, up the hill. The Del Rio store on the corner of Raya and Rancho Anapra, the main drag through the town. But these are exceptions, and all this, all of this, is founded on a belief that needs to ignore what is rapidly approaching in the truck.

This is the Colonia de Anapra, a little less than a shanty-town, trying hard to be a little bit more than a slum; poorest of all the poor colonias of Juárez. And Juárez? Juárez is the beast, the fulminating feast of violence and of the vastly unequal wielding of power; where the only true currencies are drugs, guns and violence. Juárez is a new monster in an old land: Juárez is the laboratory of our future.

Juárez, from where the pick-up truck approaches at pace, lies down the hill. Anapra is just a small feeder fish, clinging to the belly of the whale, and while it doesn’t look like the most dangerous place on earth it is here as much as anywhere else where drugs are run and bodies are hanged from telegraph poles, where dogs bark at the sound of guns in the cold desert darkness, where people vanish in the night. And the nights are long. It’s the end of October; the sun sets at six o’clock and will not rise again till seven the next morning. Thirteen hours of darkness in which all manner of evil can bloom, flowers that need no sun.

The night is yet to come.

It’s still warm. The truck cannot yet be heard, and on the corner of Rancho Anapra and Tiburón, where the paving stops and the road runs off towards the north as dirt, kids are playing in the street. Here, far from the ocean, where water is so precious, nearly all the streets have the names of fish. On Tiburón, the shark, a little girl and her friends watch her big brother wheeling his bike around in circles by the hardware store, showing off. Another group hang out by the twenty-four-hour automated water kiosk, hoping to beg a few pesos to buy some bottles. A gaggle of parents coming back from a workshop at Las Hormigas passes by, talking about what it means to be better mothers, better fathers.

Then there’s Arturo. Almost invisible, he steers his way steadily along Rancho Anapra. He glances at the kids. So serious. So seriously they play, that as Arturo weaves between them they have no idea he’s even there. There’s a smile inside him, a smile for their seriousness, and on another day he might have joked with them a little and made them laugh, but he’s too tired for that today, way too tired. Some days he helps out in an auto-shop and this is one of those days. He’s been lugging old tyres around the yard all afternoon and his shoulders ache from the effort of that while his brain aches from the effort of listening to José, the owner, complaining.

Cars come and go down the road. A bus stops and a load of maquiladora workers climb out and stand around for a while, chatting. A patrol car crawls by, a rare enough sight in Anapra. The factory workers see the car and begin to disperse into the streets of fish, but they needn’t worry, the cops are just thirsty. One of the cops gets out and wanders over to the water shop. He buys a couple of bottles and heads back to the car, ruffling the hair of one of the boys. He doesn’t give them any money. Handing one of the bottles through the window of his car to his colleague, he pulls the cap off his own. Then, as he tilts his head back to drink, the sound of the pick-up comes down the street.

Trucks come and go all the time, but the people know what this is. It’s moving fast, it has the growl of a powerful engine. It bowls into sight over the crest of the road and moves rapidly towards them. The people scatter. It might be nothing, but better to be sure. The truck gets closer; a flashy dark red body, tinted windows. Two guys in the cab, another four clinging on in the flatbed.

As if trying not to disturb the air, the cop carefully gets back in his patrol car and nods to his colleague, just as the truck reaches them, slowing right up, dropping to a crawl as it passes. The six men all stare at the cops, who make very, very sure that they do not look back.

Everyone else has disappeared.

Arturo too looks for somewhere to vanish, and quickly backs into the shaded doorway of a green house on the corner opposite, an unusual house, one of the very few with more than one floor. The four men climb down from the flatbed and, pulling out pistols, head into the hardware store. The policemen start their car and drive steadily away, back towards the city.

Arturo doesn’t feel that frightened; this is, God knows, not something new, but suddenly he feels very visible. He makes himself small in the doorway, as small as he can, and stands very still.

The four men are dragging the owner of the shop into the street. The man is called Gabriel. Arturo doesn’t really know him, nothing much beyond his name. The men are roughing him up, nothing too serious, but then, as Gabriel tries to fight back, one of them hits him on the back of his head with the heel of a pistol and he slumps to the dust, barely conscious. Arturo can see the blood even from across the street.

The men haul Gabriel onto the bed of the pick-up, and climb back in, two of them clinging to the sides and two of them lounging on an old sofa that’s been bolted to the floor. The truck makes a turn across the central reservation, heading back to Juárez, and Arturo starts to relax, but as it passes him, the driver of the truck looks over and sees him. Their eyes meet. Their eyes meet, and as they do, Arturo feels something jolt, as if the world has shuddered underneath his feet.

The man’s face is tattooed, more ink than skin; markings of a narco gang, but at this range it’s hard to see which. His head is shaven; he’s dressed, as are all the men, in a white wife-beater vest; tattoos snake all down the muscles of both arms. In slow time, the driver straightens his left arm out of the cab window, and points at Arturo. He makes a pistol with his thumb and forefinger, cocking his thumb back, aiming the gun right at Arturo, who cannot look away as the man drops his thumb, and mouths something, something Arturo cannot grasp.

The man’s head tilts back, his mouth open as he laughs. He drops his foot to the floor and the truck speeds away, back towards the city. The cops are long gone, and anyway, it’s not the police these men are scared of; they’re scared of the other pandillas, the other gangs, like the M-33, the gang whose turf this is, for now at least.

It’s over. They’ve left, and the tattooed narco is gone, but Arturo can still feel that finger pointing at him, right at his face, as if the fingertip is pressing into his forehead. It’s so strong a feeling that Arturo reaches up and tries to rub it away.

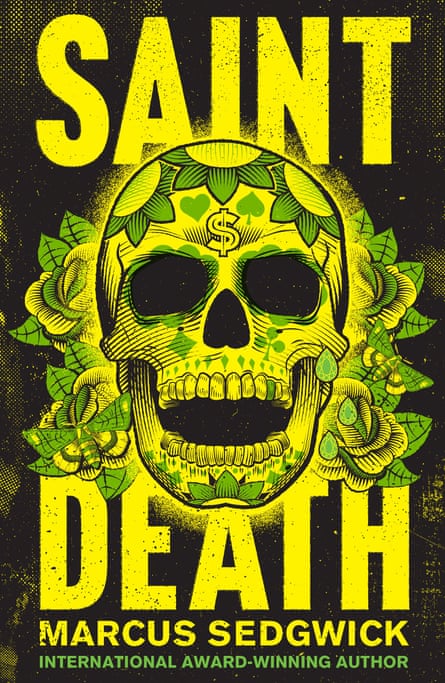

Above him, unseen, something hovers. It is something with immense power. Pure bone, and charcoal eye. Ephemeral yet eternal: the White Girl. The Beautiful Sister. The Bony Lady. Santísima Muerte. Her shroud ripples in the breeze, white wings of death. She holds a set of scales in one hand; in the other, she holds the whole world. Her skull-gaze grinning, her stare unflinching. She looks down at Arturo; she looks down at everyone.

As the truck disappears from view, Gabriel’s wife, whose name Arturo does not know, emerges into the street, screaming, her kids clinging to her legs, crying without really knowing why.

–¡Hijos de la chingada!

She screams it over and over.

–¡Hijos de la chingada!

It isn’t clear if she means the men who have taken her husband, or herself, her family. One or two people emerge from hiding and rush to give her comfort when there is no comfort to be had.

Far, so very far away, on the other side of the street, Arturo looks down and sees what he has been standing on.

Here, outside the green house, is something strange – a stretch of concrete sidewalk, where everywhere else the sidewalks are dirt. There are marks on the concrete, marks of chalk. They are lines and curves; there are arrows, and small crosses and circles within the curving lines. One device, a pair of interlocking curving arrows, is intersected by seven more arrows that point into the house. So now Arturo realises where he is, which doorway he has backed into.

Cautiously, he backs away, and looks up at Santa Muerte herself, Saint Death. La Flaquita, the Skinny Lady. She’s printed on a plastic banner that’s pinned to the wall of the house, right above the doorway. The plastic has been in the full sun for years now; her blacks have become greys, the green globe of the earth is weakened and weary. Above her, in a semicircle, it’s still just possible to make out some writing on the fading plastic: No temas a donde vayas que haz de morir donde debes.

Don’t worry where you’re going; you will die where you have to.

You have to wait until October 2016 to read more of Marcus Sedgwick’s Saint Death. Find nuggets of info about it on Marcus’s blog.