The History of Rock and Roll in 1 Song

In his new book, Greil Marcus brings us The History of Rock ’n’ Roll in Ten Songs. But rock only needs one—Jimi Hendrix's 1968 “Voodoo Child (Slight Return).”

The great Greil Marcus, whose rock-critical illuminations—in books like Mystery Train and Lipstick Traces—sent stroboscopic shafts into the black forest of my early manhood, is about to publish a volume titled The History of Rock 'n' Roll in Ten Songs.

So naturally my first thought was: I bet I can do it in five.

And my next thought was: Nah. Five songs is too many. And also too few. Five is a clutter, a randomness, a gallimaufry. If it’s not going to be 10, it’s got to be one. The history of rock 'n' roll in one song.

And if you want a song that does it all—that includes tradition, the future, outer space, electricity, armageddon, death/rebirth and the first stirrings of music itself—then there really is only one song: “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

To write about the sound of Jimi Hendrix, the actual noise of him? Wow. There’s a theme to beggar your lexicon and freeze you at the frontiers of sense. Still, what’s writing for, if not to fling itself at the unwriteable? So here we go. It’s axiomatic, really: All art aspires to the condition of music, and all music aspires to the condition of Jimi Hendrix.

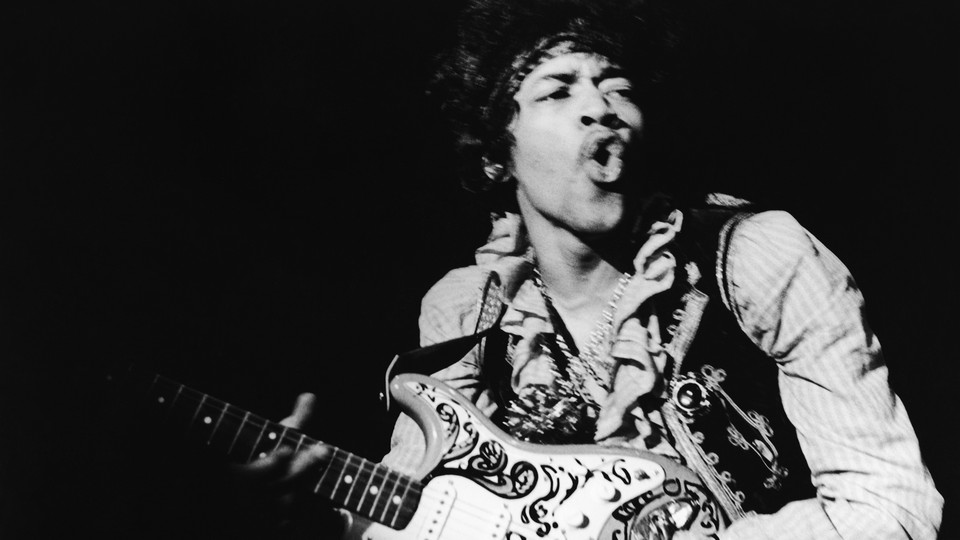

Plucked out of New York by manager/impresario Chas Chandler, he arrives in London in September 1966, lone guitarist, lanky acid popinjay, sci-fi African-American with Irish-Cherokee blood, his manners almost courtly, his speech a sing-song sequence of half-groans, groovy hesitations, delicate chuckles, fond suggestions and trailing colors, a kind of elasticized stammer. His physical presence is dramatic but somehow only partially materialized—at his edges he seemed to blur into fumes, mental incense. Behind him, for a rhythm section, Chandler puts two Brits: pasty Noel Redding, pudding-faced Mitch Mitchell. An incongruity, a mis-Mitch? Miraculously, not at all. Redding, a lapsed guitarist, is a beautiful primal bore on bass: his earth-snooze, his rooted elemental buzz, will be at the heart of this (new term) “power trio.” Mitchell, meanwhile, is jazz-demented, Elvin Jones-worshipping, breeding polyrhythms in a cymbal-wash of teenbeat frenzy—perhaps the only drummer in England capable of tracking his singer/guitarist into the Hendrixian sound-world.

And that sound-world, as it touches down in Swinging London, is already fully formed. Blues-ghosts electrically summoned, interstellar turbulence; fringed-with-incineration flights and passages of liquid gentleness; a technique that combines towering phallic exhibition with an uncanny, almost ego-less surrender to the possibilities of his instrument. These possibilities converge in the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Having stroked and pelvically jostled his guitar to a state of glimmering, agonized sensitivity, he sculpts the resulting feedback with his shoulders and extra-large hands—while Noel drones massively and nods his Afro and Mitch swarms across his tom-toms. His solos can be astral dramas or inside jokes. At his feet the pale cohort of London guitar heroes—Beck, Page, Townshend—turns paler still. Eric Clapton’s hand, as he lights his cigarette after a Hendrix show, is shaking. (Apocryphal story. But beautiful, and therefore true.) Technology is Hendrix’s medium: amplification, overdrive, the latest gear, the only-just-invented. Roger Mayer, who will design for him the Fuzz Face and Octavia effects pedals, has a background in naval intelligence, testing underwater acoustics. We'll hold hands and then we'll watch the sunrise/ From the bottom of the sea. (“Are You Experienced?”)

Hendrix writes whooshing, crazily orchestrated hippie rock with spikes of Dylanoid sense-reversal, but what he is, fundamentally, is a bluesman. As an itinerant R&B guitar-slinger in the early ‘60s he freelanced for (among others) Little Richard and Curtis Knight, acquiring road sweats, road smarts, screaming showmanship, existential momentum. The blues are his school and his laboratory, the spine of his wildness. And he doesn’t just play the blues, Jimi Hendrix has the blues: On at least a portion of his prismatic personality the blues are clanging down all day, a hail of Bibles and grand pianos. It’s one of the more lethal ironies of his art—that in the midst of multicolored stormings, and from an apparent zenith of creativity, he continually confesses his numbness, his down-ness, his separation from himself. My heart burns with feeling, oh but my mind is cold and reeling ... No sun coming through my window, feel like I’m living at the bottom of a grave ... Manic depression has captured my soul ... Because he’s a bluesman, his pain is a historical burden. At a show at Berkeley in 1970 he acknowledges the Black Panthers and then dedicates “I Don’t Live Today”—existing, nothing but existing—to “all the cats that are trying to struggle, that are going to make it anyway.” But his pain is also private. His childhood was rank with neglect; motherless Seattle winters that turned the infant Hendrix blue with cold. “I don’t think they [critics] understand my songs,” he tells a (possibly rather startled) interviewer in 1968. “They live in a different world. My world—that’s hunger, it’s the slums, raging race hatred, and happiness you can hold in your hand, nothing more!”

What else can you hold in your hand? Infinity, according to the visionary lineage of which Hendrix is undoubtedly a part. “To see the world in a grain of sand,” wrote William Blake, “And heaven in a wild flower/ Hold infinity in the palm of your hand/ And eternity in an hour.” Hendrix half-quotes Blake’s preface to Milton, in the manner that he might half-quote an Elmore James riff, on 1968’s Electric Ladyland, during the 15-minute galactic blues jam “Voodoo Chile:” “Say my arrows are made of desire, desire/ From as far away as Jupiter’s sulphur mines.” Mixing old tropes—the blood-red moon, the gypsy’s curse—with space-age lyrical junk, “Voodoo Chile” is a kind of bluesman’s “Ancient Mariner,” an imperiled soul-voyage up and down the neck of the guitar. Steve Winwood’s Hammond organ spookily swirls, and Hendrix takes us on what the critic Charles Shaar Murray calls “virtually a chronological guided tour of blues styles, starting with earliest recorded Delta blues and travelling through the electric experiments of Muddy Waters in Chicago and John Lee Hooker in Detroit to the sophisticated swing of B.B. King and the cosmic blurt of John Coltrane.”

“Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” is the final track on Electric Ladyland, and structurally a reprise in double-time of “Voodoo Chile.” But it is as if the electrified compression of the earlier, longer piece has forced Hendrix through another level of change, and he hails us now—in ringing, supernaturally authorized tones—from the far side of transformation. The intro, those snickering accents flicked from deadened strings, is almost pre-musical—it sounds like something scratching at the inside of an eggshell. Tentative at first, it resolves into a rhythm: aboriginal, radical. Dub from the back of a cave. Miles Davis hears it and falls over backward into a pile of ‘70s funk guitarists. The melody is announced, in notes opulent with wah-wah; Mitch Mitchell flexes his hi-hat; then, with a rattlesnake shake of maracas, Hendrix takes the snarling plunge into distortion—tuned down, E7 sharp 9, the “Hendrix chord.” Noel Redding meets him on the bottom string; rock and roll gapes at the impact, heavy metal kicks at the womb-wall. After three bars the guitar rears up, pluming monstrously with energy; after four Hendrix time-travels, flipping his toggle switch back and forth to create a sound like passing space-freight. Well I stand up next to a mountain, he sings, his voice supremely doubled by his instrument, chop it down with the edge of my hand. No more passivity, acid overwhelmings; no more hanging in the purple haze, not knowing if you're going up or down. The mind-fragments have formed a new shape. Pick up the pieces and make an island... Noel Redding is rumbling fixatedly; Mitch Mitchell has forsaken his customary top-of-the-kit clattering and fluttering for a kickdrum-driven, Bonhamesque downbeat. If I don’t meet you no more in this world, I’ll meet you in the next one, don’t be late. Farsightedness, death-prophecy, transdimensional challenge—Hendrix is standing outside of music. The mix pans wildly, desperately, as if overwhelmed by its own information, sizzling up into near-deafness before widening downward in a welter of noise.

We haven’t caught up to this yet. We're limping after it with handfuls of melted fuses. It’s too much, still.