/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/36056394/129375978.0.jpg)

It's one of the biggest threats to modern medicine, and it's happening right now in every corner of the world: Antibiotic resistance, when bacteria evolve so that the drugs we have don't respond anymore.

Today, the Obama administration made a long-awaited announcement about steps it would be taking to tackle drug resistance, following similarly urgent calls from other national governments earlier this year.

The reason the world is taking action is simple: antibiotic-resistant infections are a vexing problem, associated with 23,000 deaths and two million illnesses just in the US every year. Drug-resistant gonorrhea is a reality everywhere from Canada to South Africa; popular antibacterials for urinary tract infections have been rendered useless in many parts of the world; and some foretell a not too distant future in which we'll lose the ability to treat diseases like cancer and meet the demands of our antibiotic-dependent food supply. The White House put the health-care costs of resistant infections at $20-billion.

The government's announcement involved an executive order by Obama to create a task force who will come up with a plan by February 2015 to combat drug resistance over the next five years. He also called for more robust surveillance of antibiotic resistant diseases and new regulations to tackle the over-use of antibiotics in hospitals and on farms.

The announcement also came with one immediate action item: the launch of a $20-million prize for the creation of a new rapid, point-of-care diagnostic test.

Taken together, this package signals a shift in thinking: while researchers have been shrieking about this dire public-health scourge for decades, policymakers are finally moving to tackle it. As Eric Lander, co-chairman of the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), put it: "This represents a major elevation of the issue-a major upgrading of the administration's efforts to help address it."

The drug pipeline is dry

One of the scariest features of the crisis of antibiotic-resistance is that barely anybody is creating new drugs to address it. Unlike treatments for chronic diseases, people only use antibiotics for short periods of time. And we now know that we need to use them even more judiciously than we ever have, which is not exactly an appealing business proposition for large pharmaceutical companies.

For this reason, many lament the fact that the "drug pipeline is dry." Only a handful of new antibiotics have come on to the market in the last decade, and health organizations — such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America — worry that progress on new drugs is "alarmingly elusive."

The number of antibiotics approved is dropping. CDC 2013

But it's not all bad news: there are also others trying to dream up new business models that could help. Here are four ideas researchers are experimenting with, which were highlighted in today's package of recommendations. These could become powerful tools in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

1) The anti-antibiotic

Along with today's announcement from the White House came a report from PCAST with recommendations about what needs to be done to address this crisis. One necessary focus area, the report read, is "increasing the longevity of current antibiotics by improving the appropriate use of existing antibiotics." In other words, one of the best ways to resolve the antibiotic problem is to wean the world off of the drugs.

To do this, some people are already coming up with antibiotic alternatives. Take George Kenney, an MIT engineer and entrepreneur. He was concerned about the exuberant overprescribing of antibiotics to treat ear infections in children, which studies have shown has no benefit in pain reduction compared to watchful waiting and many harms. "The solution to antibiotic resistance isn't more and better antibiotics. The solution is less antibiotics," Kenney said. "I wanted to come up with a new solution that avoids antibiotics." So he went back 250 years into the annals of medicine to tackle the antibiotic challenge.

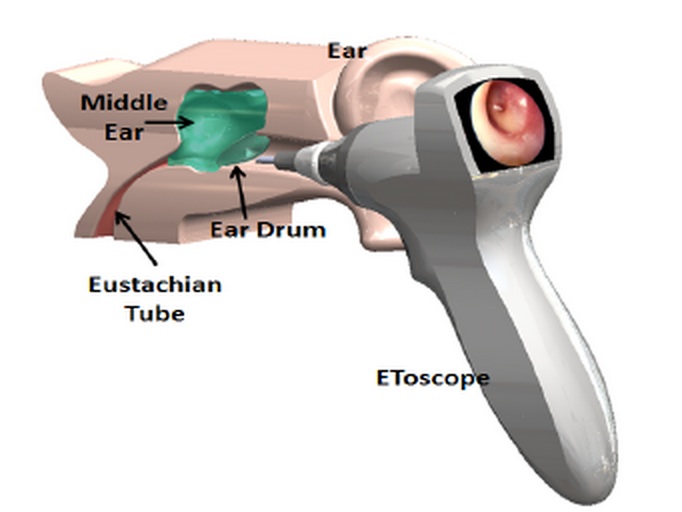

Kenney's Etoscope courtesy of EntraTympanic

Two years ago, he began working with a team of doctors and entrepreneurs from MIT, Harvard and Children's Hospital in Boston to update a technique which physicians in Europe were using in the late 1700s. Back then, long before the first antibiotic was discovered, doctors would prick a hole into a wee one's ear using a scalpel. The reason? The tiny puncture would drain fluid that had built up to create excruciating pain and pressure in the middle ear.

The Etoscope, Kenney's device, automates that procedure. If it makes it through clinical trials, it would allow physicians to do what their 18th-century counterparts did, except with the technology to ensure doctor's have enough depth perception to avoid harming the inner ear.

At the hospital level, super-cleaning robots are another ripe area for development. "Even after the best humans clean the room, they still find C.difficile spores hiding on the ceilings or around the room," said Kevin Outterson, a health law professor and antibiotics expert at Boston University. "If you have a problem with multi-drug resistance in the hospital, one idea is get more antibiotics. Another is to get a super-cleaning robot."

"If you have a problem with multi-drug resistance in the hospital, one idea is get more antibiotics. Another is to get a super-cleaning robot."

The robots use ultraviolet light to kill off potentially harmful bacteria that cleaning staff may miss. Since five percent of US hospital patients acquire infections during their stays on the ward every year, these automated super-cleaners could theoretically help avoid some of those infections and the need for more drugs to treat them, though their impact remains to be seen.

2) Better diagnostics

Another way to stave off unnecessary prescribing: better diagnosis. Big prizes are being awarded around the world for anyone who can invent better tools to diagnose disease at the point of care. The idea here is that if we could do a better job of figuring out what illness is being presented in the doctor's office, we'd prescribe fewer unnecessary antibiotics.

Today, the White House announced the launch of one such prize: $20-million for whoever comes up with a new rapid, point-of-care diagnostic test. This follows the announcement of the UK's Longitude Prize of £10 million to whoever comes up with a plan to address "one of the greatest issues of our time." The prize panel in the UK is also looking for "cheap, accurate, rapid and easy-to-use point of care test kit for bacterial infections."

In a similar spirit, Médecins Sans Frontières launched the "open source fever project." The winner here will be any inventor of a diagnostic tool that can tell the difference between fever and sepsis. Sepsis, a bacterial infection that can lead to death, requires antibiotics; a fever caused by a virus would not. The tools that come out of these prizes might be able to tell the difference.

3) Delinking the Big Pharma model

For years, the idea of "delinking" the pharmaceutical business model has been floated around in academic and health circles, and it's only now gaining mainstream notoriety and political heft. Today's PCAST report suggested delinking is one of the key alternative economic models for drug development. (The concept has also gotten a nod from the World Health Organization and Big Pharma companies like GlaxoSmithKline.)

The idea here is that traditional research and development models link the volume of patent-protected sales to the return on investment for companies. While drug companies still have their patent, they must sell as many drugs as they can—even if it's potentially dangerous for public health in the case of antibiotics. If manufacturers won't have a big market, as is the case for antibiotics, the drugs that need to be invented will never see the light of day.

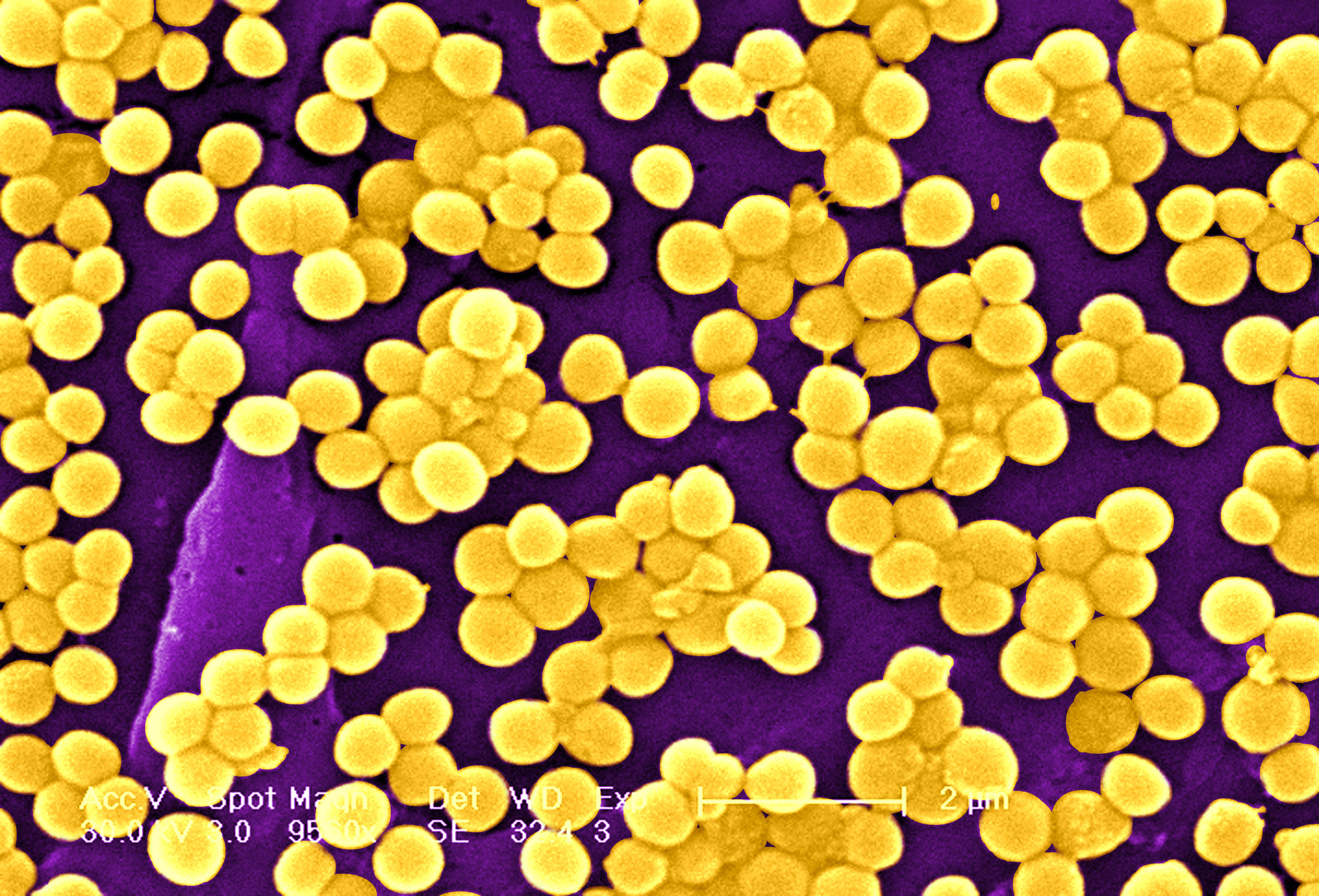

MRSA, a staph bacteria that is resistant to certain antibiotics by Universal Images Group

"The problem now is that we need new antibiotics but we don't want to use them as first-line treatments. We want them as second-, third- or fourth-line treatments," explained John-Arne Røttingen, chair of the advisory panel for the WHO's Consultative Expert Working Group on Research and Development. "We should avoid incentivizing innovators and producers of a drug to sell high volumes, and promote overuse and misuse."

"Delinkage removes the connection between funding and sales volumes," said Jamie Love, one of the leading proponents of the model and director of the NGO Knowledge Ecology International. Companies would instead be compensated for their antibiotic development on some other basis, such as grants or innovation prizes. Then, when drugs hit the market, part of the deal is that government or another health body such as a hospital would regulate how they're prescribed so that they're only used when they're really needed.

"You have a system where the patent-based incentive system is not working anymore," said Dr. Røttingen. "The innovator company wants a high-volume of sales. Society and public health needs a low volume of sales. That's why more and more, we're seeing an emerging consensus that you want to look into delinking."

4) An antibiotic user fee

One way to generate money for drug development and deter over-use is to charge a usage fee for the drugs. "With sales of antibiotics in human health and agriculture estimated at $12 billion per year, a user fee of five percent, for example," the PCAST report reads, "would generate $600 million that could be devoted to incentivize the development of new antibiotics."

Of course, the PCAST also called for a lot more than just user fees. Said Kevin Outterson, "They called for a dramatic increase in federal funding to prevent an antibiotic apocalypse, an additional $1.25 billion per year." This includes doubling federal spending on antibiotic resistance research, surveillance and spending. Pouring federal funding into antibiotic-resistance isn't an alternative business model of course, but, as Outterson said, "Given the costs and risks, this is money exceedingly well spent."