Hello, Maria! If you missed last week's edition – how to own your story, a vintage love letter to solitude and the rewards of getting lost, Leonard Bernstein on believing in each other, how Proust can help you stop letting habit blunt your aliveness, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

Hello, Maria! If you missed last week's edition – how to own your story, a vintage love letter to solitude and the rewards of getting lost, Leonard Bernstein on believing in each other, how Proust can help you stop letting habit blunt your aliveness, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this, please consider supporting with a modest donation – every little bit helps, and comes enormously appreciated.

“Where the myth fails, human love begins," Anaïs Nin wrote in her diary in 1941. "Then we love a human being, not our dream, but a human being with flaws." Indeed, just like perfectionism kills creativity, it also kills love – the more we mythologize and idealize the person we love, the more disillusioned and disheartened we grow as we come to know their imperfect humanity which, if untainted by these blinding ideals, is the very wellspring of true love. That is what playwright Tom Stoppard captured in what is perhaps the greatest definition of love, in his notion of "the mask slipped from the face," the stripping of the idealized projection, the surrender to the beautiful imperfection of a human being.

“Where the myth fails, human love begins," Anaïs Nin wrote in her diary in 1941. "Then we love a human being, not our dream, but a human being with flaws." Indeed, just like perfectionism kills creativity, it also kills love – the more we mythologize and idealize the person we love, the more disillusioned and disheartened we grow as we come to know their imperfect humanity which, if untainted by these blinding ideals, is the very wellspring of true love. That is what playwright Tom Stoppard captured in what is perhaps the greatest definition of love, in his notion of "the mask slipped from the face," the stripping of the idealized projection, the surrender to the beautiful imperfection of a human being.

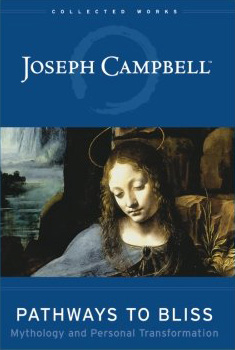

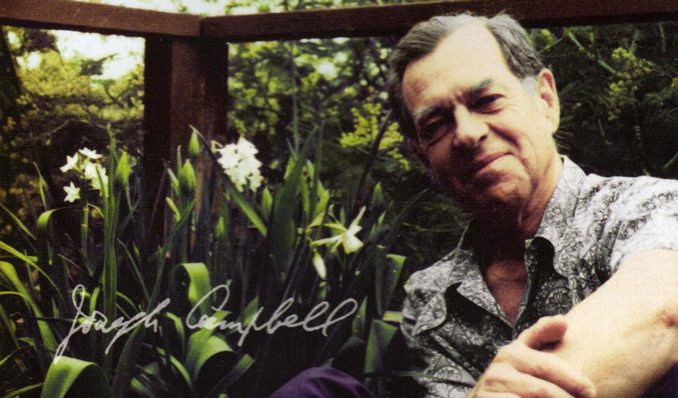

How to successfully navigate love's maze of ideal and reality is what master-mythologist and writer Joseph Campbell explores in a section of the posthumously published Pathways to Bliss: Mythology and Personal Transformation (public library), which offers a more personal complement to Campbell's influential writings on bliss and the power of myth.

A century and a half after Stendhal's insightful ideas on why we fall out of love, Campbell builds upon Carl Jung’s psychological theory of anima (the female ideal in the masculine unconscious) and animus (the male ideal in the feminine unconscious), and explores how our clinging to those ideals blinds us to the most rewarding part of romance.

His focus on marriage is especially timely and poignant today, when the institution of marriage is being reimagined to be more inclusive and more just, which also means it's being challenged to rise to higher standards of integrity. Campbell writes:

Two people meet and fall in love. Then they marry, and the real Sam or Suzy begins to show through the fantasy, and, boy, is it a shock. So a lot of little boys and girls just withdraw their anima or animus. They get a divorce and wait for another receptive person, pitch the woo again, and, uh-oh, another shock. And so on and so forth.

Two people meet and fall in love. Then they marry, and the real Sam or Suzy begins to show through the fantasy, and, boy, is it a shock. So a lot of little boys and girls just withdraw their anima or animus. They get a divorce and wait for another receptive person, pitch the woo again, and, uh-oh, another shock. And so on and so forth.

Now the one undeniable fact: this disillusion is inevitable. You had to ideal. You married did ideal, then along comes a fact that does not correspond to that ideal. You suddenly notice things that do not quite fit with your projection. So what are you going to do when that happens? There's only one attitude that will solve the situation: compassion. This poor, poor fact that I married does not correspond to my ideal; it's only a human being. Well, I'm a human being, too. So I'll meet a human being for a change; I'll live with it and be nice to it, showing compassion for the fallibilities that I myself have certainly brought to life as a human being.

Decades later, Dan Savage would come to call this "the price of admission" – the most potent antidote to the perilous myth of "the one," which is build upon a scaffolding of illusion and unattainable ideals. Campbell captures this with clarity at once grounding and elevating:

Perfection is inhuman. Human beings are not perfect. What evokes our love – and I mean love, not lust – is the imperfection of the human being. So, when the imperfection of the real person, compared to the ideal of your animus or anima, peeks through, say, this is a challenge to my compassion. Then make a try, and something might begin to get going here. You might begin to be quit of your fix on your anima.

Perfection is inhuman. Human beings are not perfect. What evokes our love – and I mean love, not lust – is the imperfection of the human being. So, when the imperfection of the real person, compared to the ideal of your animus or anima, peeks through, say, this is a challenge to my compassion. Then make a try, and something might begin to get going here. You might begin to be quit of your fix on your anima.

Illustration by Olimpia Zagnoli from Mister Horizontal & Miss Vertical by Noémie Révah

In a sentiment that calls to mind the great Zen teacher D.T. Suzuki's assertion that "the ego-shell in which we live is the hardest thing to outgrow," Campbell adds:

It's just as bad to be fixed on your anima and miss as to be fixed on your persona: you've got to get free of that. And the lesson of life is to release you from it.

It's just as bad to be fixed on your anima and miss as to be fixed on your persona: you've got to get free of that. And the lesson of life is to release you from it.

[...]

The principle of compassion is that which converts disillusionment into a participatory companionship. So when the fact shows through the animus or anima, what you must render is compassion. This is the basic love, the charity, that turns a critic into a living human being who has something to give to – as well as to demand of – the world.

This is how one is to deal with animus and anima disillusionment... That's reality evoking a new depth of reality in yourself, because you're imperfect, too. You may not know it. The world is a constellation of imperfections, and you, perhaps, are the most imperfect of all. By your love for the world you name it accurately and without pity and love what you have thus named... This discovery can help you save your marriage.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak for Open House for Butterflies by Ruth Krauss

And yet, paradoxically, Campbell argues that this is the task of life – not to avoid these anima and animus projections, which we all carry, but to confront them with courage and do the work of disillusionment so we can get to the imperfect realness of which true love is woven. (This is what Rilke meant when he counseled his young friend that "for one human being to love another ... is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks … the work for which all other work is but preparation.") Campbell speaks to the necessity of both the preparation and the work itself:

One of the boldest things you could possibly do would be to marry that ideal that you've fallen for. Then you face a real job, because everything has been projected onto him or her. This goes beyond lust; this is something that goes way down. It pulls everything out. This anima/animus is the fish line that has caught your whole unconscious, and everything's going to come up – the Midgard Serpent, everything down in the bottom. This is what you marry.

One of the boldest things you could possibly do would be to marry that ideal that you've fallen for. Then you face a real job, because everything has been projected onto him or her. This goes beyond lust; this is something that goes way down. It pulls everything out. This anima/animus is the fish line that has caught your whole unconscious, and everything's going to come up – the Midgard Serpent, everything down in the bottom. This is what you marry.

Pathways to Bliss is a magnificent, richly insightful read in its entirety. Complement it with Campbell on the eleven stages of the hero's journey – which, in a way, apply just as aptly to the lover's journey – and his timeless wisdom on how to have a fulfilling life, then revisit the great Wendell Berry on marriage and Susan Sontag on the complexities of love.

:: FORWARD TO A FRIEND :: SHARE / READ MORE

–––

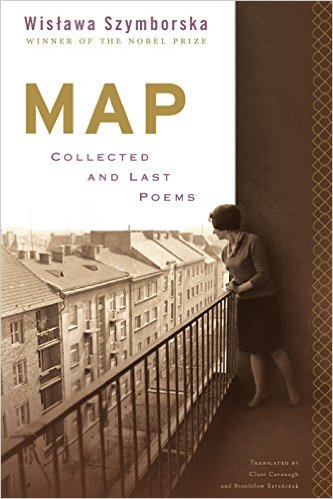

One spring evening not too long ago, I joined the wonderful Amanda Palmer on a small and friendly stage at Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music and we read some Polish poetry together from Map: Collected and Last Poems (public library) – the work of Nobel laureate Wislawa Szymborska (July 2, 1923–February 1, 2012), for whom we share deep affection and admiration.

One spring evening not too long ago, I joined the wonderful Amanda Palmer on a small and friendly stage at Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music and we read some Polish poetry together from Map: Collected and Last Poems (public library) – the work of Nobel laureate Wislawa Szymborska (July 2, 1923–February 1, 2012), for whom we share deep affection and admiration.

When Szymborska was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996 “for poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality,” the Nobel commission rightly called her “the Mozart of poetry” – but, wary of robbing her poetry of its remarkable dimension, added that it also emanates “something of the fury of Beethoven.” I often say that she is nothing short of Bach, the supreme enchanter of the human spirit.

Amanda has previously lent her beautiful voice to my favorite Szymborska poem, "Possibilities," and she now lends it to another favorite from this final volume, "Life While-You-Wait" – a bittersweet ode to life's string of unrepeatable moments, each the final point in a fractal decision tree of what-ifs that add up to our destiny, and a gentle invitation to soften the edges of the heart as we meet ourselves along the continuum of our becoming.

Please enjoy:

LIFE WHILE-YOU-WAIT

LIFE WHILE-YOU-WAIT

Life While-You-Wait.

Performance without rehearsal.

Body without alterations.

Head without premeditation.

I know nothing of the role I play.

I only know it's mine. I can't exchange it.

I have to guess on the spot

just what this play's all about.

Ill-prepared for the privilege of living,

I can barely keep up with the pace that the action demands.

I improvise, although I loathe improvisation.

I trip at every step over my own ignorance.

I can't conceal my hayseed manners.

My instincts are for happy histrionics.

Stage fright makes excuses for me, which humiliate me more.

Extenuating circumstances strike me as cruel.

Words and impulses you can't take back,

stars you'll never get counted,

your character like a raincoat you button on the run –

the pitiful results of all this unexpectedness.

If only I could just rehearse one Wednesday in advance,

or repeat a single Thursday that has passed!

But here comes Friday with a script I haven't seen.

Is it fair, I ask

(my voice a little hoarse,

since I couldn't even clear my throat offstage).

You'd be wrong to think that it's just a slapdash quiz

taken in makeshift accommodations. Oh no.

I'm standing on the set and I see how strong it is.

The props are surprisingly precise.

The machine rotating the stage has been around even longer.

The farthest galaxies have been turned on.

Oh no, there's no question, this must be the premiere.

And whatever I do

will become forever what I've done.

Map: Collected and Last Poems, translated by Clare Cavanagh and Stanislaw Baranczak, is a work of immense beauty in its 464-page totality. Complement it with Amanda's bewitching reading of "Possibilities" and join me in supporting her on Patreon – her art, like Brain Pickings, is free and made possible by donations. In fact, she wrote a whole fantastic book about the mutually dignifying and gratifying gift of patronage.

:: FORWARD TO A FRIEND :: SHARE / READ MORE

–––

“Death is our friend," wrote Rilke in a beautiful 1923 letter, "precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love.” And yet most of us spend our days dreading this inevitable and natural conclusion to the human journey, casting death as life's ultimate and most hateful antagonist – a fear that invariably contracts our aliveness.

“Death is our friend," wrote Rilke in a beautiful 1923 letter, "precisely because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, that is natural, that is love.” And yet most of us spend our days dreading this inevitable and natural conclusion to the human journey, casting death as life's ultimate and most hateful antagonist – a fear that invariably contracts our aliveness.

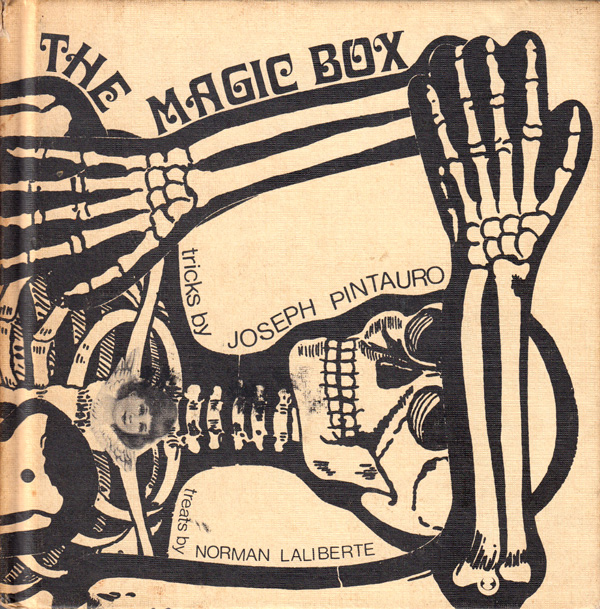

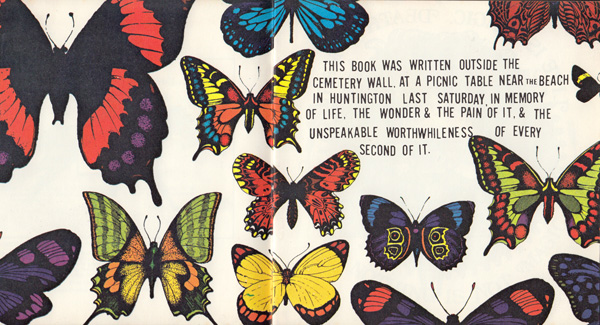

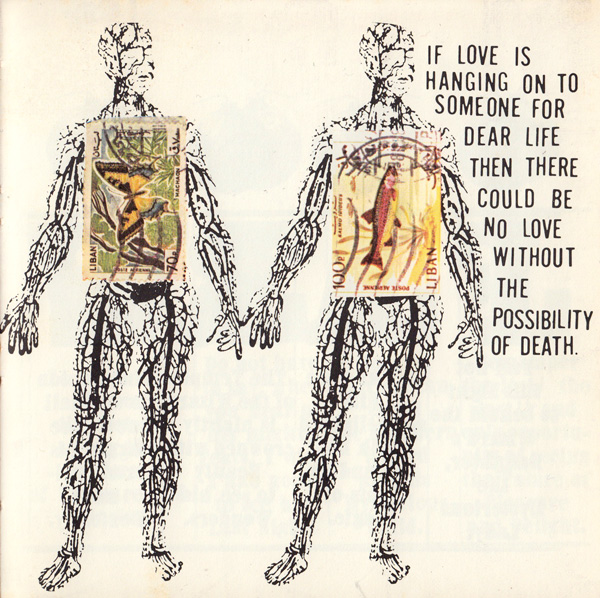

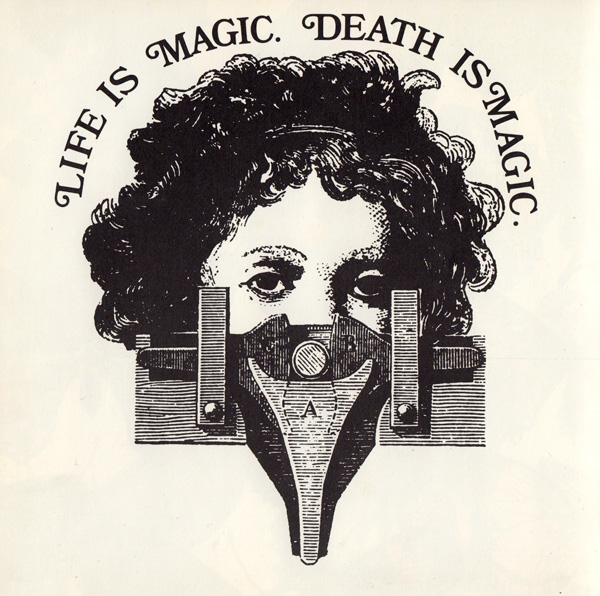

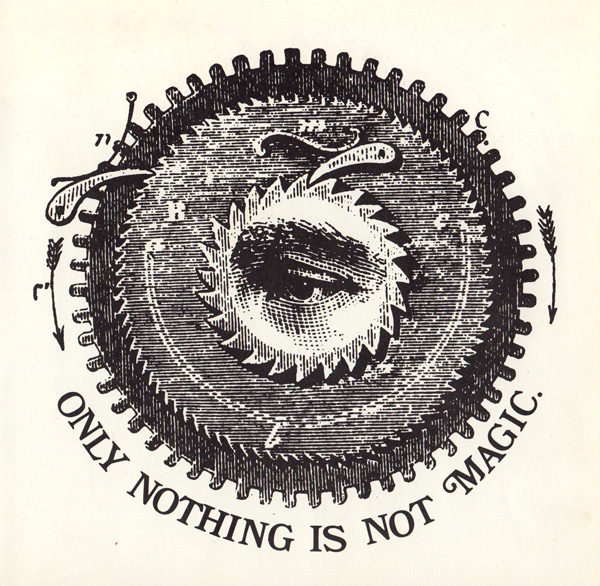

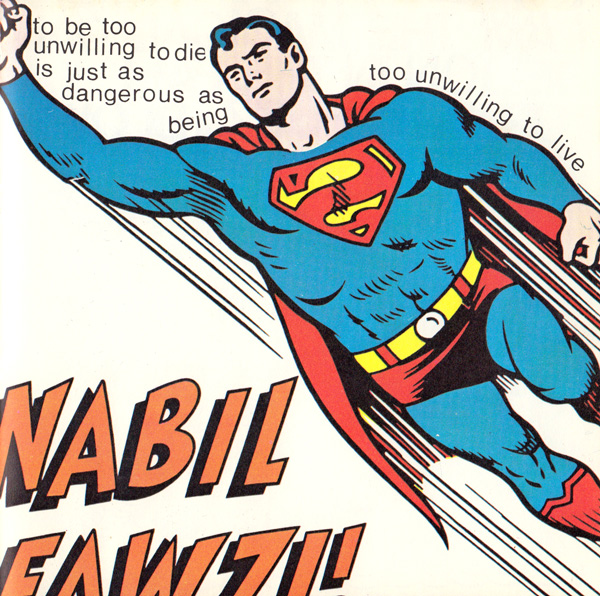

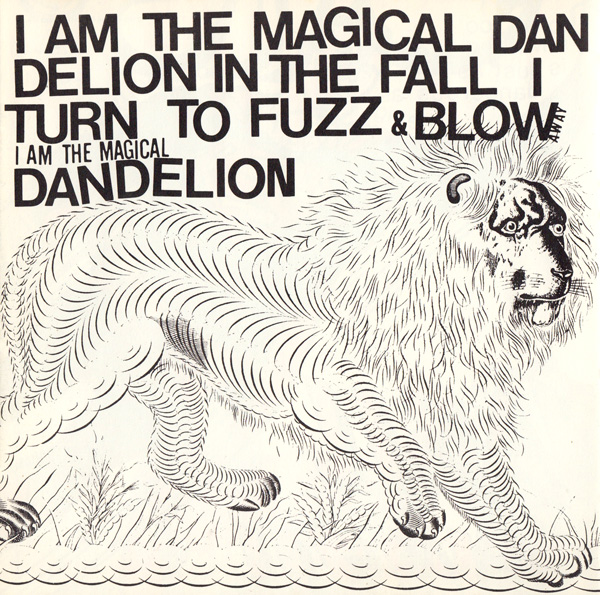

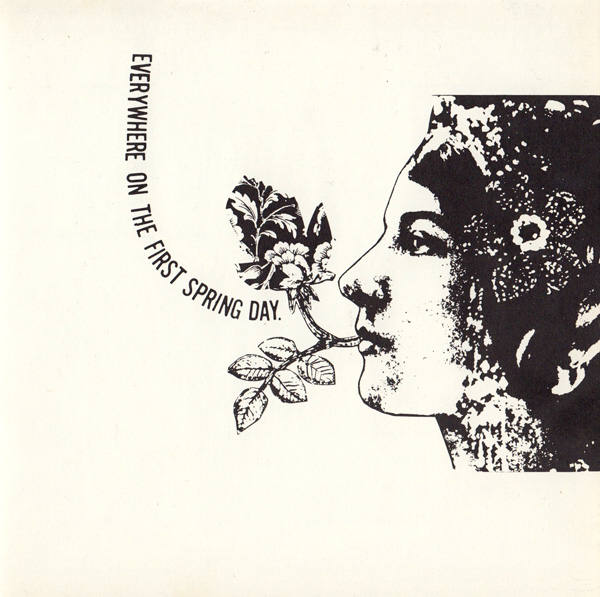

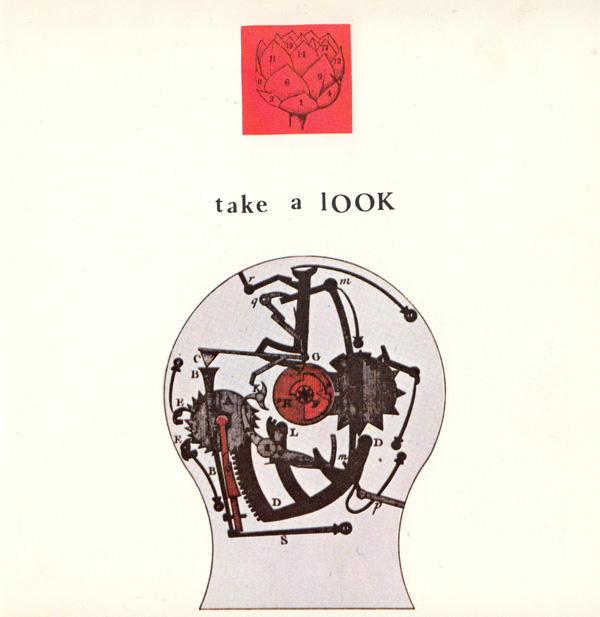

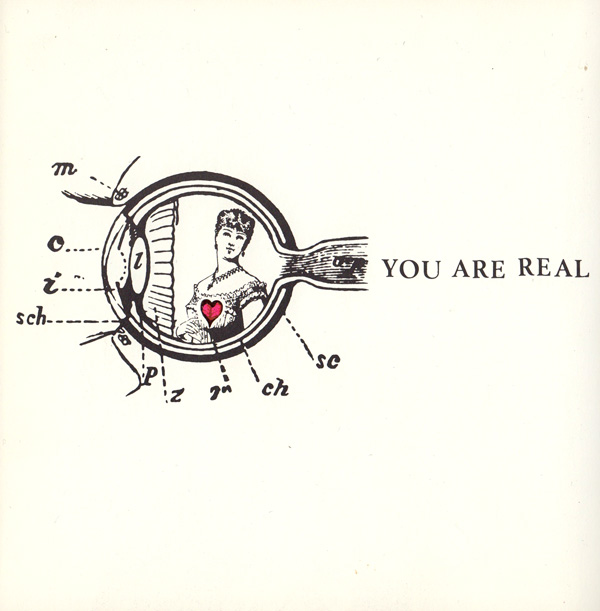

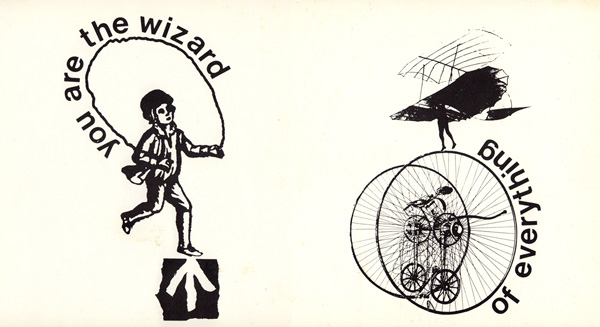

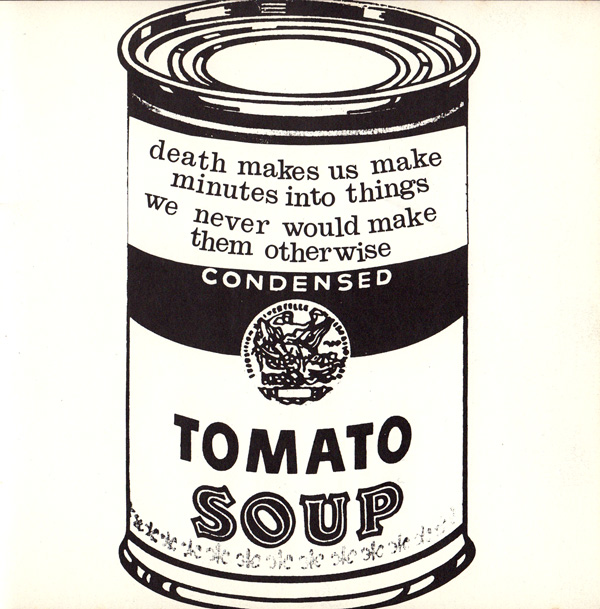

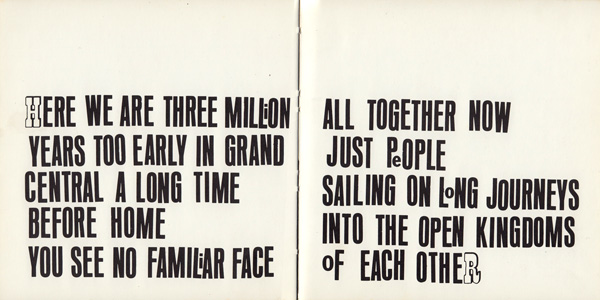

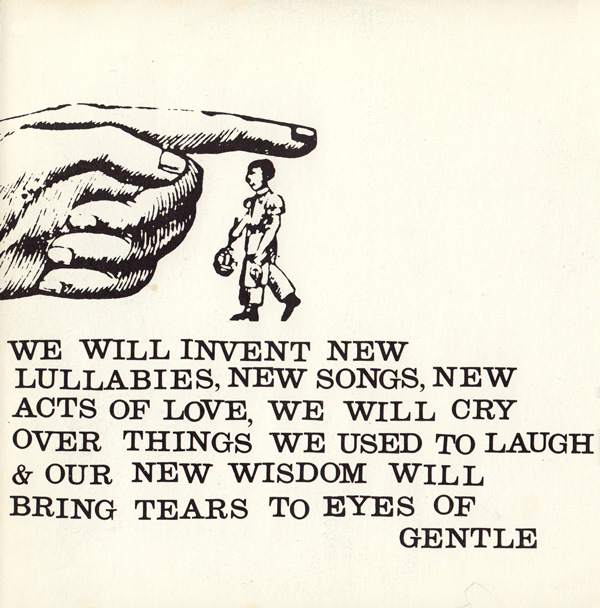

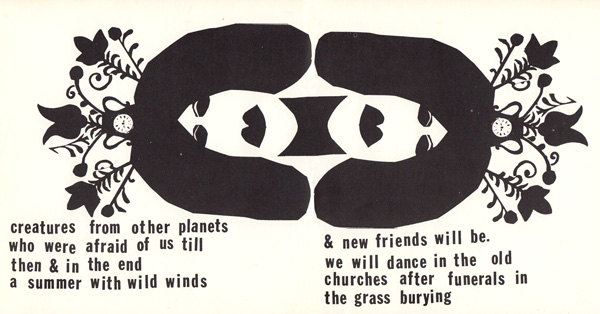

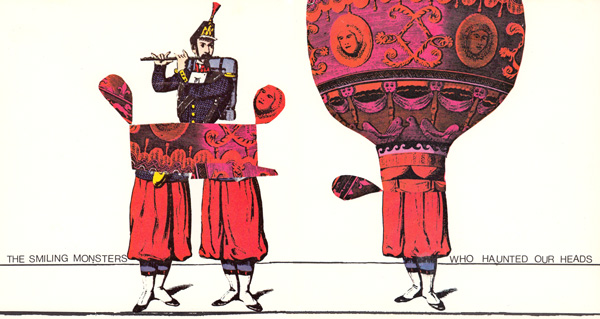

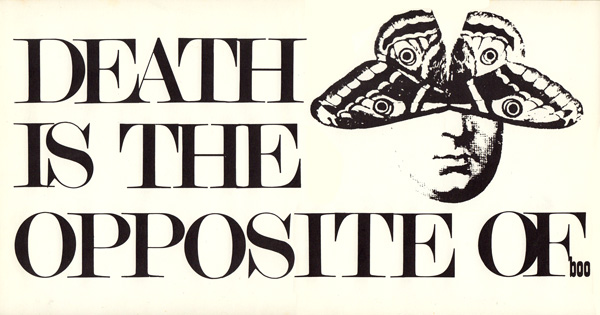

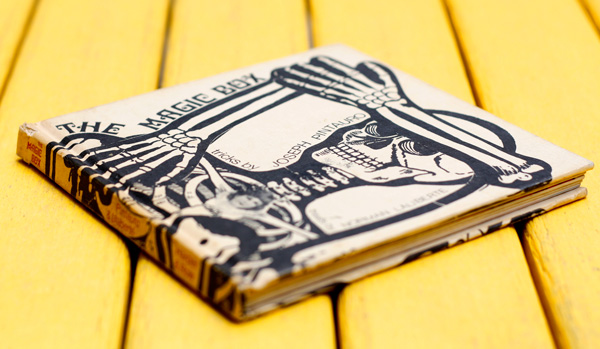

How to have a more expansive and enlivening relationship with our mortality is what writer Joseph Pintauro and artist Norman Laliberté explore half a century after Rilke in the 1970 treasure The Magic Box (public library) – a most unusual and wonderful children's book for adults about life and death, the seasonality of being, and the beauty that springs from our impermanence.

A grownup counterpart to the most intelligent and imaginative children's books about making sense of death, this vintage gem is part of a marvelous limited-edition set by Pintauro and Laliberté called The Rainbow Box – a collection of four such psychedelic art books, one for each season of the year: this one for autumn, The Peace Box for winter, The Rabbit Box for spring, and A Box of Sun for summer.

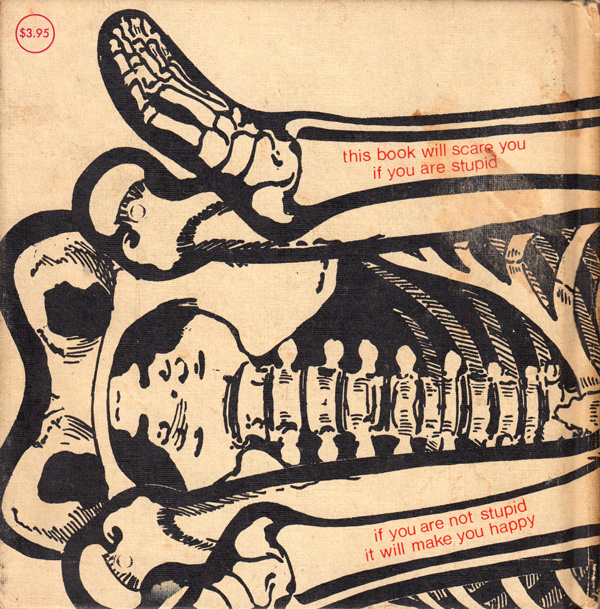

The Magic Box presents a series of short, vitalizing meditations on mortality, illustrated with beautiful typographic art and collage incorporating Victorian engravings reminiscent of Donald Barthelme's only children's book. The back cover captures Pintauro's charming tone of earnest, uncynical irreverence:

this book will scare you if you are stupid

this book will scare you if you are stupid

if you are not stupid it will make you happy

Stupidity aside, if you are sensitive and wholehearted, it will most definitely make you rapturous with delight – here is a peek inside:

Complement The Magic Box, immeasurably wonderful in its entirety, with Emerson on how to live with maximum aliveness and a very different contemporary take on the seasonality of life: Italian artist Alessandro Sanna's breathtaking The River.

:: FORWARD TO A FRIEND :: SHARE / READ MORE

–––

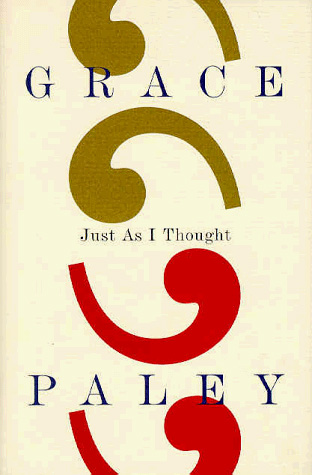

"As a person she is tolerant and easygoing, as a user of words, merciless," the editors of The Paris Review wrote in the introduction to their 1992 interview with poet, short story writer, educator, and activist Grace Paley (December 11, 1922–August 22, 2007). Although Paley herself never graduated from college, she went on to become one of the most beloved and influential teachers of writing – both formally, through her professorships at Sarah Lawrence, Columbia, Syracuse University, and City College of New York, and informally, through her insightful lectures, interviews, essays, and reviews. The best of those are collected in Just As I Thought (public library) – a magnificent anthology of Paley's nonfiction, which cumulatively presents a sort of oblique autobiography of the celebrated writer.

"As a person she is tolerant and easygoing, as a user of words, merciless," the editors of The Paris Review wrote in the introduction to their 1992 interview with poet, short story writer, educator, and activist Grace Paley (December 11, 1922–August 22, 2007). Although Paley herself never graduated from college, she went on to become one of the most beloved and influential teachers of writing – both formally, through her professorships at Sarah Lawrence, Columbia, Syracuse University, and City College of New York, and informally, through her insightful lectures, interviews, essays, and reviews. The best of those are collected in Just As I Thought (public library) – a magnificent anthology of Paley's nonfiction, which cumulatively presents a sort of oblique autobiography of the celebrated writer.

In one of the most stimulating pieces in the volume – a lecture from the mid-1960s titled "The Value of Not Understanding Everything," which does for writing what Thoreau did for the spirit in his beautiful meditation on the value of "useful ignorance" – Paley examines the single most fruitful disposition for great writing:

The difference between writers and critics is that in order to function in their trade, writers must live in the world, and critics, to survive in the world, must live in literature. That’s why writers in their own work need have nothing to do with criticism, no matter on what level.

The difference between writers and critics is that in order to function in their trade, writers must live in the world, and critics, to survive in the world, must live in literature. That’s why writers in their own work need have nothing to do with criticism, no matter on what level.

[...]

What the writer is interested in is life, life as he is nearly living it... Some people have to live first and write later, like Proust. More writers are like Yeats, who was always being tempted from his craft of verse, but not seriously enough to cut down on production.

Therein, she argues, lies the key to why writers write. Echoing Joan Didion – “Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write," she wryly observed in the classic Why I Write – Paley reflects:

One of the reasons writers are so much more interested in life than others who just go on living all the time is that what the writer doesn’t understand the first thing about is just what he acts like such a specialist about – and that is life. And the reason he writes is to explain it all to himself, and the less he understands to begin with, the more he probably writes. And he takes his ununderstanding, whatever it is – the face of wealth, the collapse of his father’s pride, the misuses of love, hopeless poverty – he simply never gets over it. He’s like an idealist who marries nearly the same woman over and over. He tries to write with different names and faces, using different professions and labors, other forms to travel the shortest distance to the way things really are.

In other words, the poor writer – presumably in an intellectual profession – really oughtn’t to know what he’s talking about.

One of the reasons writers are so much more interested in life than others who just go on living all the time is that what the writer doesn’t understand the first thing about is just what he acts like such a specialist about – and that is life. And the reason he writes is to explain it all to himself, and the less he understands to begin with, the more he probably writes. And he takes his ununderstanding, whatever it is – the face of wealth, the collapse of his father’s pride, the misuses of love, hopeless poverty – he simply never gets over it. He’s like an idealist who marries nearly the same woman over and over. He tries to write with different names and faces, using different professions and labors, other forms to travel the shortest distance to the way things really are.

In other words, the poor writer – presumably in an intellectual profession – really oughtn’t to know what he’s talking about.

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo from Enormous Smallness by Mathhew Burgess, a picture-book biography of E.E. Cummings

With a skeptical eye to the familiar "write what you know" dictum of creative writing classes, Paley makes a case for the opposite approach in extracting the juiciest raw material for great writing:

I would suggest something different... what are some of the things you don’t understand at all?

I would suggest something different... what are some of the things you don’t understand at all?

[...]

You might try your father and mother for a starter. You’ve seen them so closely that they ought to be absolutely mysterious. What’s kept them together these thirty years? Or why is your father’s second wife no better than his first? If, before you sit down with paper and pencil to deal with them, it all comes suddenly clear and you find yourself mumbling, Of course, he’s a sadist and she’s a masochist, and you think you have the answer – drop the subject.

In classic Paley style, where what appears to be subtle sarcasm turns out to be a vehicle for great sagacity, she adds:

If, in casting about for suitable areas of ignorance, you fail because you understand yourself (and too well), your school friends, as well as the global balance of terror, and you can also see your last Saturday-night date blistery in the hot light of truth – but you still love books and the idea of writing – you might make a first-class critic... In areas in which you are very smart you might try writing history or criticism, and then you can know and tell how all the mystery of America flows out from under Huck Finn’s raft; where you are kind of dumb, write a story or a novel, depending on the depth and breadth of your dumbness...

If, in casting about for suitable areas of ignorance, you fail because you understand yourself (and too well), your school friends, as well as the global balance of terror, and you can also see your last Saturday-night date blistery in the hot light of truth – but you still love books and the idea of writing – you might make a first-class critic... In areas in which you are very smart you might try writing history or criticism, and then you can know and tell how all the mystery of America flows out from under Huck Finn’s raft; where you are kind of dumb, write a story or a novel, depending on the depth and breadth of your dumbness...

When you have invented all the facts to make a story and get somehow to the truth of the mystery and you can’t dig up another question – change the subject.

Cautioning that writing fails when "the tension and the mystery and the question are gone," she concludes:

The writer is not some kind of phony historian who runs around answering everyone’s questions with made-up characters tying up loose ends. She is nothing but a questioner.

The writer is not some kind of phony historian who runs around answering everyone’s questions with made-up characters tying up loose ends. She is nothing but a questioner.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from The Big Green Book by Robert Graves

A few years later, Paley revisits the subject in a 1970 piece from the same volume titled "Some Notes on Teaching," in which she offers fifteen insights as useful to aspiring writers as they are to professional writers like herself "who must begin again and again in order to get anywhere at all." Noting that she aims to "stay as ignorant in the art of teaching" as she wants her students to be in the art of writing, she observes that the assignments she gives are usually questions which have stumped her, ones which she herself is still pursuing.

She first turns to the integrity of language, so often squeezed out of writers by their education:

Literature has something to do with language. There’s probably a natural grammar at the tip of your tongue... If you say what’s on your mind in the language that comes to you from your parents and your street and friends, you’ll probably say something beautiful. Still, if you weren’t a tough, recalcitrant kid, that language may have been destroyed by the tongues of schoolteachers who were ashamed of interesting homes, inflection, and language and left them all for correct usage.

Literature has something to do with language. There’s probably a natural grammar at the tip of your tongue... If you say what’s on your mind in the language that comes to you from your parents and your street and friends, you’ll probably say something beautiful. Still, if you weren’t a tough, recalcitrant kid, that language may have been destroyed by the tongues of schoolteachers who were ashamed of interesting homes, inflection, and language and left them all for correct usage.

She then offers an assignment that puts into practice this essential art of "ununderstanding," with the instruction of being repeated whenever necessary:

Write a story, a first-person narrative in the voice of someone with whom you’re in conflict. Someone who disturbs you, worries you, someone you don’t understand. Use a situation you don’t understand.

Write a story, a first-person narrative in the voice of someone with whom you’re in conflict. Someone who disturbs you, worries you, someone you don’t understand. Use a situation you don’t understand.

Paley raises a dissenting voice in literary history's many-bodied chorus of celebrated writers who extol the creative benefits of keeping a diary:

No personal journals, please, for about a year... When you find only yourself interesting, you’re boring. When I find only myself interesting, I’m a conceited bore. When I’m interested in you, I’m interesting.

No personal journals, please, for about a year... When you find only yourself interesting, you’re boring. When I find only myself interesting, I’m a conceited bore. When I’m interested in you, I’m interesting.

(It is worth offering a counterpoint here, by way of Vivian Gornick's excellent advice on how to write personal narrative of universal interest and Cheryl Strayed's observation that "when you’re speaking in the truest, most intimate voice about your life, you are speaking with the universal voice.”)

Ignoring John Steinbeck's admonition – "If there is a magic in story writing, and I am convinced there is," he asserted in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, "no one has ever been able to reduce it to a recipe that can be passed from one person to another." – Paley offers if not a recipe then a pantry inventory of the two key ingredients necessary for great storytelling:

It’s possible to write about anything in the world, but the slightest story ought to contain the facts of money and blood in order to be interesting to adults. That is, everybody continues on this earth by courtesy of certain economic arrangements; people are rich or poor, make a living or don’t have to, are useful to systems or superfluous. And blood – the way people live as families or outside families or in the creation of family, sisters, sons, fathers, the bloody ties. Trivial work ignores these two facts.

It’s possible to write about anything in the world, but the slightest story ought to contain the facts of money and blood in order to be interesting to adults. That is, everybody continues on this earth by courtesy of certain economic arrangements; people are rich or poor, make a living or don’t have to, are useful to systems or superfluous. And blood – the way people live as families or outside families or in the creation of family, sisters, sons, fathers, the bloody ties. Trivial work ignores these two facts.

Art from the original edition of Henry Miller's Money and How It Gets That Way

She returns to the essential fork in the vocational road that separates writers from critics:

Luckily for art, life is difficult, hard to understand, useless, and mysterious. Luckily for artists, they don’t require art to do a good day’s work. But critics and teachers do. A book, a story, should be smarter than its author. It is the critic or the teacher in you or me who cleverly outwits the characters with the power of prior knowledge of meetings and ends.

Luckily for art, life is difficult, hard to understand, useless, and mysterious. Luckily for artists, they don’t require art to do a good day’s work. But critics and teachers do. A book, a story, should be smarter than its author. It is the critic or the teacher in you or me who cleverly outwits the characters with the power of prior knowledge of meetings and ends.

Stay open and ignorant.

Echoing Nadine Gordimer's enduring wisdom on the writer's task "to go on writing the truth as he sees it," Paley adds:

A student says, Why do you keep saying a work of art? You’re right. It’s a bad habit. I mean to say a work of truth.

A student says, Why do you keep saying a work of art? You’re right. It’s a bad habit. I mean to say a work of truth.

What does it mean To Tell the Truth?

It means – for me – to remove all lies... I am, like most of you, a middle-class person of articulate origins. Like you I was considered verbal and talented, and then improved upon by interested persons. These are some of the lies that have to be removed:

a. The lie of injustice to characters.

b. The lie of writing to an editor’s taste, or a teacher’s.

c. The lie of writing to your best friend’s taste.

d. The lie of the approximate word.

e. The lie of unnecessary adjectives.

f. The lie of the brilliant sentence you love the most.

She ends by urging aspiring writers to learn from the masters of this art of truth-telling:

Don’t go through life without reading the autobiographies of

Don’t go through life without reading the autobiographies of

Emma Goldman

Prince Kropotkin

Malcolm X

To that, I would heartily add the autobiography of Oliver Sacks – had she lived to read it, Paley may well have concurred.

Complement Paley's Just As I Thought with this growing archive of great writers' advice on the craft, including Virginia Woolf on writing and self-doubt, Susan Sontag's advice to aspiring writers, Ann Patchett on the importance of self-forgiveness, William Zinsser on how to write well about science, and Neil Gaiman's eight rules of writing.

:: FORWARD TO A FRIEND :: SHARE / READ MORE

–––

Although Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. used Christian social ethics and the New Testament concept of "love" heavily in his writings and speeches, he was as influenced by Eastern spiritual traditions, Gandhi's political writings, Buddhism's notion of the interconnectedness of all beings, and Ancient Greek philosophy. His enduring ethos, at its core, is nonreligious – rather, it champions a set of moral, spiritual, and civic responsibilities that fortify our humanity, individually and collectively.

Although Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. used Christian social ethics and the New Testament concept of "love" heavily in his writings and speeches, he was as influenced by Eastern spiritual traditions, Gandhi's political writings, Buddhism's notion of the interconnectedness of all beings, and Ancient Greek philosophy. His enduring ethos, at its core, is nonreligious – rather, it champions a set of moral, spiritual, and civic responsibilities that fortify our humanity, individually and collectively.

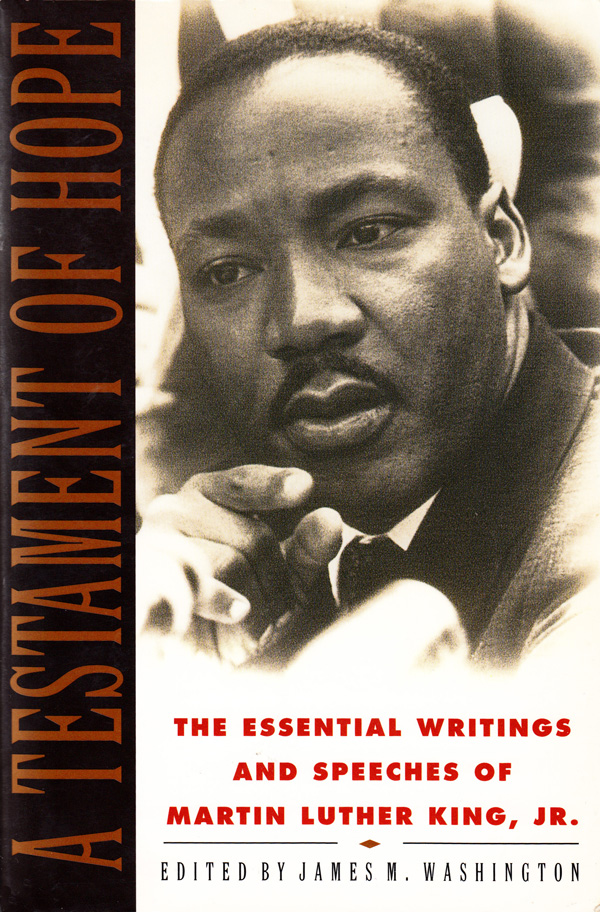

Nowhere does he transmute spiritual ideas from various traditions into secular principles more masterfully than in his extraordinary 1958 essay "An Experiment in Love," in which he examines the six essential principles of his philosophy of nonviolence, debunks popular misconceptions about it, and considers how these basic tenets can be used in guiding any successful movement of nonviolent resistance. Penned five years before his famous Letter from Birmingham City Jail and exactly a decade before his assassination, the essay was eventually included in the indispensable A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (public library) – required reading for every human being with a clicking mind and a ticking heart.

In the first of the six basic philosophies, Dr. King addresses the tendency to mistake nonviolence for passivity, pointing out that it is a form not of cowardice but of courage:

It must be emphasized that nonviolent resistance is not a method for cowards; it does resist. If one uses this method because he is afraid or merely because he lacks the instruments of violence, he is not truly nonviolent. This is why Gandhi often said that if cowardice is the only alternative to violence, it is better to fight... The way of nonviolent resistance ... is ultimately the way of the strong man. It is not a method of stagnant passivity... For while the nonviolent resister is passive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, his mind and his emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong. The method is passive physically but strongly active spiritually. It is not passive non-resistance to evil, it is active nonviolent resistance to evil.

It must be emphasized that nonviolent resistance is not a method for cowards; it does resist. If one uses this method because he is afraid or merely because he lacks the instruments of violence, he is not truly nonviolent. This is why Gandhi often said that if cowardice is the only alternative to violence, it is better to fight... The way of nonviolent resistance ... is ultimately the way of the strong man. It is not a method of stagnant passivity... For while the nonviolent resister is passive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, his mind and his emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong. The method is passive physically but strongly active spiritually. It is not passive non-resistance to evil, it is active nonviolent resistance to evil.

He turns to the second tenet of nonviolence:

Nonviolence ... does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding. The nonviolent resister must often express his protest through noncooperatoin or boycotts, but he realizes that these are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation. The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness.

Nonviolence ... does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding. The nonviolent resister must often express his protest through noncooperatoin or boycotts, but he realizes that these are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation. The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness.

Illustration by Olivier Tallec from Waterloo and Trafalgar

In considering the third characteristic of nonviolence, Dr. King appeals to the conscientious recognition that those who perpetrate violence are often victims themselves:

The attack is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil. It is the evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons victimized by the evil. If he is opposing racial injustice, the nonviolent resister has the vision to see that the basic tension is not between the races... The tension is, at bottom, between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness.... We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may be unjust.

The attack is directed against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil. It is the evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons victimized by the evil. If he is opposing racial injustice, the nonviolent resister has the vision to see that the basic tension is not between the races... The tension is, at bottom, between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness.... We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may be unjust.

Out of this recognition flows the fourth tenet:

Nonviolent resistance [requires] a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back... The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. He does not seek to dodge jail. If going to jail is necessary, he enters it "as a bridegroom enters the bride's chamber."

Nonviolent resistance [requires] a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back... The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. He does not seek to dodge jail. If going to jail is necessary, he enters it "as a bridegroom enters the bride's chamber."

That, in fact, is precisely how Dr. King himself entered jail five years later. To those skeptical of the value of turning the other cheek, he offers:

Unearned suffering is redemptive. Suffering, the nonviolent resister realizes, has tremendous educational and transforming possibilities.

Unearned suffering is redemptive. Suffering, the nonviolent resister realizes, has tremendous educational and transforming possibilities.

The fifth basic philosophy turns the fourth inward and arrives at the most central point of the essay – the noblest use of what we call "love":

Nonviolent resistance ... avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. The nonviolent resister would contend that in the struggle for human dignity, the oppressed people of the world must not succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter or indulging in hate campaigns. To retaliate in kind would do nothing but intensify the existence of hate in the universe. Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can only be done by projecting the ethic of love to the center of our lives.

Nonviolent resistance ... avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. The nonviolent resister would contend that in the struggle for human dignity, the oppressed people of the world must not succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter or indulging in hate campaigns. To retaliate in kind would do nothing but intensify the existence of hate in the universe. Along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate. This can only be done by projecting the ethic of love to the center of our lives.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from Let's Be Enemies by Janice May Udry

Here, Dr. King turns to Ancient Greek philosophy, pointing out that the love he speaks of is not the sentimental or affectionate kind – "it would be nonsense to urge men to love their oppressors in an affectionate sense," he readily acknowledges – but love in the sense of understanding and redemptive goodwill. The Greeks called this agape – a love distinctly different from the eros, reserved for our lovers, or philia, with which we love our friends and family. Dr. King explains:

Agape means understanding, redeeming good will for all men. It is an overflowing love which is purely spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless, and creative. It is not set in motion by any quality or function of its object... Agape is disinterested love. It is a love in which the individual seeks not his own good, but the good of his neighbor. Agape does not begin by discriminating between worthy and unworthy people, or any qualities people possess. It begins by loving others for their sakes. It is an entirely "neighbor-regarding concern for others," which discovers the neighbor in every man it meets. Therefore, agape makes no distinction between friends and enemy; it is directed toward both. If one loves an individual merely on account of his friendliness, he loves him for the sake of the benefits to be gained from the friendship, rather than for the friend's own sake. Consequently, the best way to assure oneself that love is disinterested is to have love for the enemy-neighbor from whom you can expect no good in return, but only hostility and persecution.

Agape means understanding, redeeming good will for all men. It is an overflowing love which is purely spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless, and creative. It is not set in motion by any quality or function of its object... Agape is disinterested love. It is a love in which the individual seeks not his own good, but the good of his neighbor. Agape does not begin by discriminating between worthy and unworthy people, or any qualities people possess. It begins by loving others for their sakes. It is an entirely "neighbor-regarding concern for others," which discovers the neighbor in every man it meets. Therefore, agape makes no distinction between friends and enemy; it is directed toward both. If one loves an individual merely on account of his friendliness, he loves him for the sake of the benefits to be gained from the friendship, rather than for the friend's own sake. Consequently, the best way to assure oneself that love is disinterested is to have love for the enemy-neighbor from whom you can expect no good in return, but only hostility and persecution.

This notion is nearly identical to one of Buddhism's four brahmaviharas, or divine attitudes – the concept of Metta, often translated as lovingkindness or benevolence. The parallel speaks not only to Dr. King's extraordinarily diverse intellectual toolkit of influences and inspirations – a high form of combinatorial creativity necessary for any meaningful contribution to humanity's common record – but also to the core commonalities between the world's major spiritual and philosophical traditions.

In a sentiment that Margaret Mead and James Baldwin would echo twelve years later in their spectacular conversation on race – "In any oppressive situation both groups suffer, the oppressors and the oppressed," Mead observed, asserting that the oppressors suffer morally with the recognition of what they're committing, which Baldwin noted is "a worse kind of suffering" – Dr. King adds:

Another basic point about agape is that it springs from the need of the other person – his need for belonging to the best in the human family... Since the white man's personality is greatly distorted by segregation, and his soul is greatly scarred, he needs the love of the Negro. The Negro must love the white man, because the white man needs his love to remove his tensions, insecurities, and fears.

Another basic point about agape is that it springs from the need of the other person – his need for belonging to the best in the human family... Since the white man's personality is greatly distorted by segregation, and his soul is greatly scarred, he needs the love of the Negro. The Negro must love the white man, because the white man needs his love to remove his tensions, insecurities, and fears.

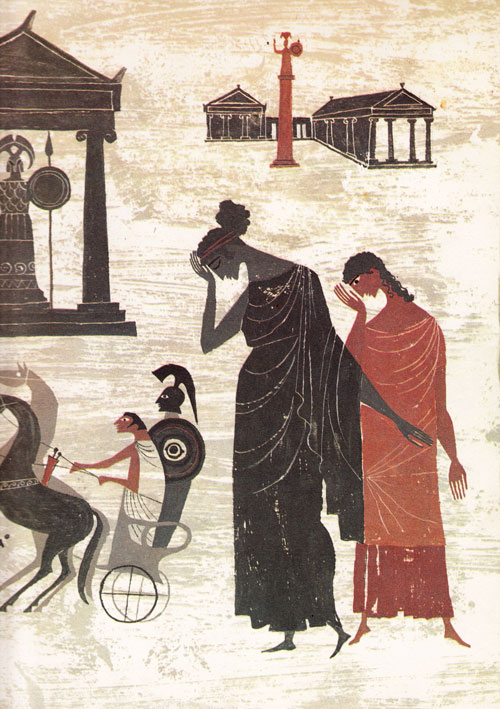

Illustration by Alice and Martin Provensen for a vintage children's-book adaptation of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey

At the heart of agape, he argues, is the notion of forgiveness – something Mead and Baldwin also explored with great intellectual elegance. Dr. King writes:

Agape is not a weak, passive love. It is love in action... Agape is a willingness to go to any length to restore community... It is a willingness to forgive, not seven times, but seventy times seven to restore community.... If I respond to hate with a reciprocal hate I do nothing but intensify the cleavage in broken community. I can only close the gap in broken community by meeting hate with love.

Agape is not a weak, passive love. It is love in action... Agape is a willingness to go to any length to restore community... It is a willingness to forgive, not seven times, but seventy times seven to restore community.... If I respond to hate with a reciprocal hate I do nothing but intensify the cleavage in broken community. I can only close the gap in broken community by meeting hate with love.

With this, he turns to the sixth and final principle of nonviolence as a force of justice, undergirded by the nonreligious form of spirituality that Dani Shapiro elegantly termed "an animating presence" and Alan Lightman described as the transcendence of "this strange and shimmering world." Dr. King writes:

Nonviolent resistance ... is base don the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. Consequently, the believer in nonviolence has deep faith in the future. This faith is another reason why the nonviolent resister can accept suffering without retaliation. For he knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. It is true that there are devout believers in nonviolence who find it difficult to believe in a personal God. But even these persons believe in the existence of some creative force that works for universal wholeness. Whether we call it an unconscious process, an impersonal Brahman, or a Personal Being of matchless power of infinite love, there is a creative force in this universe that works to bring the disconnected aspects of reality into a harmonious whole.

Nonviolent resistance ... is base don the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. Consequently, the believer in nonviolence has deep faith in the future. This faith is another reason why the nonviolent resister can accept suffering without retaliation. For he knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. It is true that there are devout believers in nonviolence who find it difficult to believe in a personal God. But even these persons believe in the existence of some creative force that works for universal wholeness. Whether we call it an unconscious process, an impersonal Brahman, or a Personal Being of matchless power of infinite love, there is a creative force in this universe that works to bring the disconnected aspects of reality into a harmonious whole.

A Testament of Hope is an absolutely essential read in its totality. Complement it with Dr. King on the two types of law, Albert Einstein's little-known correspondence with W.E.B. Du Bois on racial justice, and Tolstoy and Gandhi's equally forgotten but immensely timely correspondence on why we hurt each other.

:: FORWARD TO A FRIEND :: SHARE / READ MORE

If you enjoyed this week's newsletter, please consider helping me keep it going with a modest donation.