The show opened and then it closed. Or closed and then opened.

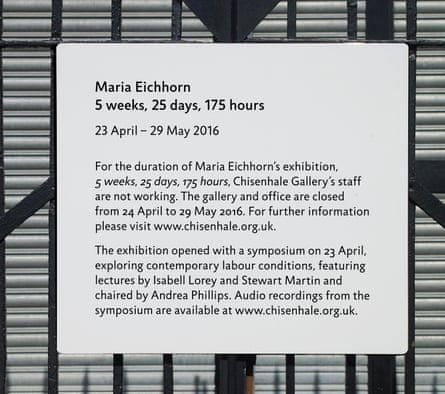

At 6pm on 23 April, following a day-long crowded symposium in the otherwise empty Chisenhale Gallery in London, the doors and gates were locked, and a sign affixed to the railings. And that was it. Or rather, not it at all.

Maria Eichhorn’s 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours presents visitors with a closed and unoccupied gallery. The staff, including gallery director Polly Staple, will be on free time and full pay until 29 May. Phones will not be answered, emails to gallery addresses will be deleted, except for a dedicated account that will be checked every Wednesday. There’s nothing to see, but lots to think about. Who is paying for this time? What does this withdrawal from work and suspension of the gallery’s activities mean? It is not a strike or boycott, nor a protest in any obvious way.

The artist says she has not assigned Chisenhale’s employees any tasks other than not to work for the gallery. “The institution itself and the actual exhibition are not closed, but rather displaced into the public sphere and society,” she says. “[And] when the gallery’s employees come back to work, there will not be a great deal of emails waiting to be dealt with, thankfully.”

She has also stipulated Chisenhale should not be used for other purposes during its closure – not rented for profit or otherwise capitalised, nor turned over for socially engaged good works. The lights are off and – as one angry contributor remarked during Saturday’s symposium – “the walls as bare as a speculator’s unoccupied loft apartment on the Thames”. It is a caesura, a break, an interruption.

How will Eichhorn, born in southern Germany and now living in Berlin, know if her artwork has succeeded? “This is not for me to say,” she told me after the symposium. Only in its afterlife, she believes, can the exhibition be understood. That, too, is where meaning will be generated.

She has previous form. In 2011, Eichhorn used her budget for an exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern, in Switzerland, to pay for much-needed renovations to the building, leaving the galleries themselves empty. What we might call her work was delegated to the builders who completed the renovations. “It’s not easy,” she remarked at the symposium, “to distinguish what is part of the work and what is not.” The less there is to see, the more there is to say, runs the critical adage. Some galleries might close and you wouldn’t even notice, remarked Liverpool Biennial director Sally Tallant from the floor.

The artistic gesture of closing a gallery also has a history. In 1969, conceptual artist Robert Barry left a sign on the door of Art + Project Gallery in Amsterdam, telling visitors it would be closed for the duration of his exhibition. Michael Asher removed a partition wall in an LA commercial gallery in 1974, to reveal the work that goes on behind the scenes. Like those restaurants where the kitchen is visible to diners as they eat, this is a risky move. Abominable chefs and gallerists who behave like martinets beware this sort of exposure: it puts people off their food, and the art.

But Eichhorn exposes very little. Instead she has sent everyone home, having already interviewed all the staff about the pleasures and pressures of their jobs – interviews written up in a publication on the gallery’s website, along with an audio recording of the symposium and the speakers’ papers. There’s an extreme balance here between closure and exposure, withholding and negation. The closure might also aggravate the vulnerable relationships a mid-sized, nominally public gallery has with its audience, stakeholders, funders, trustees and private and corporate patrons. Chisenhale is part publicly funded, but Staple told Eichhorn in her interview that she spends 75% of her time fundraising.

Non-shows like this can reveal the cracks; they can also widen them. Spanish artist Santiago Sierra sealed off the entrance to his show at Lisson Gallery in 2002 with a barricade of corrugated metal, and, for his official exhibition in the Spanish Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, posted guards at the entrance. Entry was allowed only to Spanish passport holders, who found the interior unrefurbished and unlit, with leftover rubbish from the previous architectural biennale strewn on the floor.

Is Eichhorn making just another futile art gesture to resist consumption or marketability? As the closed sign was being screwed to the Chisenhale gate, a collector was trying to negotiate purchase of the work. Someone else suggested the show might go on tour. Such provocations can be empty, nihilistic, annoying. Withdrawal can act as a passive-aggressive slight, the effect one of alienation. But Eichhorn’s purpose is, I think, more generative.

At the core of her latest work is the idea she is gifting the gallery and staff some time, as much as a break. The concept of free time and our striving for a mythic “work-life balance” are worth consideration. When working life is so precarious and borderless, frequently conducted on short term or zero-hours contracts, and our social lives become ever more instrumentalised in the service of it, balance goes out the window.

Our unpaid hours are filled with “networking”, fielding emails, constructing work-related online identities, boosting our professional affiliations and always being available in nebulous ways. As we nurture the professional relationships that substitute for friendships, our lives become ever more hijacked by employers, and a sense of vulnerability and guilt about our productivity.

Robert Rauschenberg once said he wanted to work in the gap between art and life. He could not have known the ramifications of his words today. Caring for ourselves and others – children, parents, colleagues, lovers, work contacts and the unseen and unknowable members of our wider professional circle – entails an expenditure of feelings and affects, in an attempt to balance a debt that can never be paid. We must always be on, even when we are off.

Who, you may ask, is Maria Eichhorn to give anyone permission to stop working, or even to demand they do? But I can think of many art exhibitions, filled with objects, hours of video, images and signs, that offer less; whose satisfactions are more meagre and arcane; whose purposes are less graspable and concrete, their impact dissipating the moment you leave.

Eichhorn’s project is as much situational as it is institutional critique – a way of treating the institution itself as the subject of the work. Those of us who are not the beneficiaries of the free time given to Chisenhale’s staff might ask what, if anything, is in it for us? Our freedom is to go and do something else, to withdraw, to work precariously, or to do nothing – the greatest gift of all.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion