Andrew Marr: Great Scots

15 August 2014

Broadcaster and journalist Andrew Marr writes for BBC Arts on the challenges of making his BBC Two series, Great Scots: The Writers Who Shaped a Nation.

The Writers Who Shaped a Nation

Scotland's modern literature is scandalously under-appreciated: what better time than just ahead of the independence referendum for the BBC to have another go at reminding the whole UK about the glories they are missing?

But, I have to admit, there were two added impulses. First, we haven't been terribly good at bringing literature to the screen – certainly not compared to art, science and history.

We haven't been terribly good at bringing literature to the screen

Second, this might provide another way for today's Scots to get a grip on some of the issues about security, patriotism - living "in bed with an (English) elephant"- via the lives and writing of some of her greatest authors.

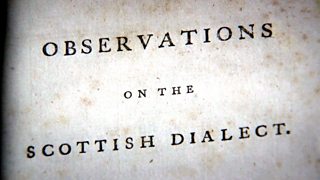

Which authors? Well, there are plenty of "obvious" choices who haven't made the cut. First, and most controversially, I decided that we should focus on writers after the union of 1707 - so we could concentrate on Scottish experiences inside the UK.

This excludes at least three of Scotland's greatest poets – William Dunbar, Robert Henryson and Gavin Douglas. They are all top-notch mediaeval talents and far too little known, but their experiences of Scotland were so remote from 2014 that, I felt, "another time...".

I have also excluded many of the most popular Scottish writers of modern times, either because they were flinty, southern-based Unionists or because they didn't seem to me to have much to say about contemporary politics.

James Boswell

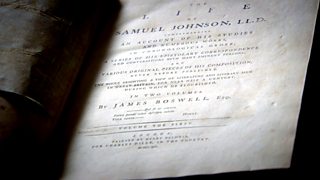

So, the first film focuses on James Boswell, who is surely the greatest Scottish prose writer of the 18th century.

Boswell, to my mind, is a true father of modern journalism

The only serious challenger is Tobias Smollett, but he spent most of his writing life south of the border or with the Royal Navy.

Boswell, to my mind, in his candour and shameless pursuit of the most interesting people in Europe, is a true father of modern journalism. I’ve adored his writing all my adult life.

This meant that the first film was always going to have a slightly "better together" feel to it, because Boswell’s great coup was his friendship with Samuel Johnson, and the gigantic masterpiece of biography that came from it - the first true, warts-and-all literary biography based on proper first-hand research. Boswell would be a little-known figure had he never met Johnson.

Johnson would be remembered as a poet and essayist but certainly wouldn't be the second most quoted Englishman after Shakespeare, had he never met the bumptious young Scot.

Less Boswell without Johnson, less Johnson without Boswell - a union of very unequal minds which nevertheless worked brilliantly.

I hope, however, that we have shown something of the agonizing cost of the Union to Boswell and many other Scots of the mid-18th century. They loved the opportunities London gave them – as do I – but they yearned for the diminished country of their birth.

Sir Walter Scott

The second film deals with the most successful novelist of Scotland has ever produced, memorialised in the world's largest monument to a writer, and indeed Edinburgh's main railway station.

The tension between Burns and Scott was there from the beginning

But Sir Walter Scott is now rather looked down upon as a wordy, Tory Unionist snob. It's a terribly unfair view of a complex, proud Scot.

This film explores how it was, and still is, possible to be a patriot and to believe in the union. Inevitably, however, Robert Burns with his powerful romantic nationalism and his sympathy for the rebel workers and Democrats of the time, emerges as the glamorous counterweight to Scott.

The tension between Burns and Scott was there from the beginning and still divides literary Scotland today.

The Scott film takes us towards the Scotland of the British Empire, which suffered its greatest shock with the First World War, a war in which proportionally more Scots died and were injured than from any other part of the Empire.

One of those fighting was a younger postman's son called Christopher Grieve, who went on to be the great and controversial prophet of modern nationalism.

Hugh MacDiarmid

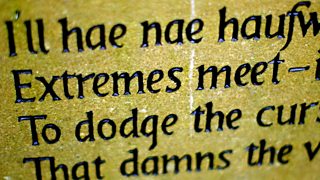

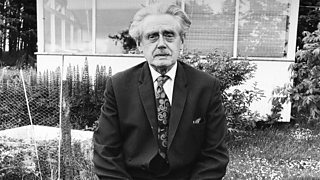

Changing his name to Hugh MacDiarmid, Grieve launched a one-man intellectual war aimed at establishing a Scottish communist republic.

MacDiarmid is one of the greatest poets produced by Britain in the last century, a world-scale genius

Famously, he was thrown out of the communist party for his nationalism and thrown out of the National Party of Scotland (forerunner of the SNP) for his communism. He'd always be, as he said, "whaur extremes meet."

Some modern nationalists tend to regard him as an embarrassment, and No campaigners certainly don't like to hear his name. In a long life as a self-appointed gadfly and provocateur, MacDiarmid certainly adopted unpleasant and extreme positions – Stalinist, Anglophobe, sometime admirer of Fascists.

The problem is that he is also one of the greatest poets produced by Britain in the last century, a world-scale genius.

And by showing Scots that it was possible to imagine and work on the biggest possible scale, inside Scotland and here and now, he provoked a renaissance in Scottish writing and the arts generally which continues to this day.

Nobody would go to him now for a political manifesto but Scotland's self-confidence owes everything to this difficult, prickly, brilliant man.

None of these stories are easy or obvious. All of them, I feel, deserve to be much better known on the eve of Scotland's referendum.

MacDiarmid clips

Exclusive Readings

-

BBC Arts presents exclusive readings to accompany the Great Scots television series.

TV & Radio

-

![]()

Episode One: James Boswell

The series begins with an unlikely literary hero, James Boswell, a man torn between his patriotic duty at home and his desire for fame and adventure elsewhere.

-

![]()

Episode Two: Sir Walter Scott

The second episode examines the life of Walter Scott, a prolific novelist and poet who wrote swashbuckling tales of romance and derring-do.

-

![]()

Episode Three: Hugh MacDiarmid

Andrew Marr looks into the life of Scotland's most bothersome poet, Hugh MacDiarmid.

-

![]()

Radio 3: Sunday Feature

Stuart Kelly speaks to Denise Mina, Allan Massie and David Greig about the role Scottish artists are playing in the Independence Debate.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms