Between 1983 and 1987, Susan Rogers didn’t really sleep. She’d work late into the night at a recording studio, then just three or four hours later would be woken up to head back in again, year after year – always at the beck and call of Prince as he answered his own relentless creativity. “I didn’t get a chance to form memories because I didn’t sleep long enough to form them,” she says. “People remind me of the wildest stuff and I say: are you sure I was there?”

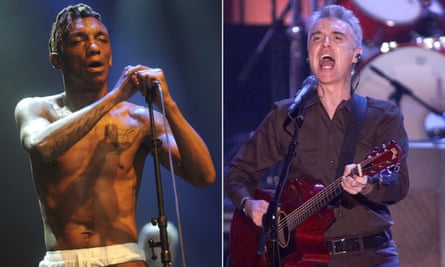

Rogers, 61, is an extraordinary figure, a working-class autodidact who, as one of the tiny number of female recording engineers in the US, ended up helping to craft some of the greatest pop songs ever, from When Doves Cry to Raspberry Beret. The Prince sessions ensured a further decade of work with the likes of David Byrne, Barenaked Ladies and Tricky before she finally graduated from high school at 44 and then obtained a PhD in music and psychology.

In between teaching at Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music, she is now a sought-after public speaker, dispensing a lifetime’s worth of knowledge at hip events such as Red Bull Music Academy and this weekend’s Ableton Loop conference.

She knew this – or something like it – would be her path from a young age. “Playing records lit me up like a Christmas tree,” she says down the line from her office. “It felt like a calling: this is me, this is the street that I live on.” It was the early 60s, and the Beatles were a hit in Rogers’ kindergarten playground, as they were everywhere else. “There was this funny feeling of doubt – I didn’t seem to be feeling the same way the other kids were. But the first time I heard James Brown’s Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag, I thought: ‘This is the shit.’”

Later, in high school, “kids were either fans of Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck or Eric Clapton – which guitarist you chose indicated which tribe you were in. It was always Page for me. That dirtier blues thing just felt right, and that feeling of correctness is actually the basis of a producer’s value system. Your job is to be on the other side of the glass listening to a performance and comparing what you’re hearing with what you’d like to be hearing. Can this band do it? Can they get there from here? It’s then a little like blind dating – you talk about what you have in common, what each of you wants.”

But production work was a long way off. Rogers’ mother died when she was 14 and her father needed three jobs to make ends meet. She left high school to help and got a job in a biomedical lab removing valves from pig hearts. She also got married. “An extreme mistake,” she says. “Fortunately for me, the person I was married to was a really bad man – he was physically abusive. Fortunate because I could leave him and not look back.”

At 21, she was divorced and living in southern California with a roommate called Louise. “We both wanted to be in the music business – Louise because she wanted to marry a rock star. She was beautiful, feminine, wore dresses and perfume, and slept with everybody. That’s what Louise exchanged to get in the door. I wasn’t cut from that cloth; I was a more intellectual type. So I began studying.”

She bought textbooks on electronics, acoustics and recording techniques, and got a job repairing recording consoles through an ad in the Los Angeles Times. She graduated to a recording studio owned by Graham Nash and David Crosby, and then heard that her favourite artist, Prince, was on the hunt for an audio technician.

“When the Dirty Mind album came out, it blew my mind,” she says. “This guy was a true artist, who was willing to completely offend his core audience. Songs about incest and oral sex were not cool in the R&B community. But it was such a brilliant tactical move on his part – he realised he was going to have to leapfrog over his competition and get the attention and acclaim of critics. I fantasised about the opportunity just to meet him, never mind work with him.”

But she got the job and moved to Minneapolis in 1983, becoming part of Prince’s coterie of strong, creative women, who also included singer Sheila E, guitarist Wendy Melvoin and pianist Lisa Coleman. Why did he love working with women so much? “Obviously, he was a heterosexual man and enjoyed having beautiful women around!” she says. “But he needed to be the alpha male to get done what he needed to get done; he couldn’t spend any mental energy battling with people for dominance or position. If you wanted your own way of doing things, you shouldn’t be working for Prince – and women are, it’s safe to say, more inclined to let a man lead. He also liked outsiders and liked feeling like one himself. There weren’t many female technicians, so I was a rare bird and he liked the rare birds.”

Despite him being the dominant creative force, Rogers says that Prince gave the women “a lot of power and responsibility”.

In her case, this involved being swiftly promoted from technician to engineer, a role she had rarely taken on previously. But she quickly grasped his sound. “He liked very clean and punchy drum sounds – a lot of attack,” she says. “We’d take a kick drum and pull all the mid-range out of it, very similar to a heavy-metal kick drum. He liked a very prominent hi-hat and claps to be low-pitched, fat and sustained. He wanted rhythm guitar to be clean and direct, using really thick 11-gauge strings. It was really hard for me to unlearn Prince – everything I did after that reflected his ear, for better and worse.”

The pair would often set up in Minnesotan warehouses rather than expensive studios; there were no producers or songwriters involved. Rogers would arrive first and get everything ready. “We would work fast and quietly, without speaking. He would first record the drums from top to bottom, listening to nothing, just with the song in his head. Next thing, he’d play the bass part, the keyboard part, the rhythm guitar. Then his vocals, alone in the control room.”

As the song was built up, doubts would plague him. “He’d get really quiet, and that’s when he started getting rid of things, like the bass on When Doves Cry. Or he’d strip down the whole top line and then change the tempo with the tape machine to see if it was going to work better slower or faster.” With a song finished, he would often head out to a club afterwards and would end up performing: “The poor kid was so naturally shy, he didn’t want to mingle because he didn’t have anything to say – he wanted to be on stage playing,” she says.

He’d invariably woo a woman nonetheless, but couldn’t resist going back to the studio in the middle of the night. “He’d have her sit there in the control room while we continued working. The girls sat there until they got bored and went home, with Prince saying: ‘Sorry, baby, I’m almost done.’”

On tour, he would do a four-hour sound check, a three-hour show and then head to a hired studio. “He would consider 1am, after playing a stadium show, the point at which his day could begin,” Rogers says. “One of Jimi Hendrix’s former girlfriends said Jimi would put on his guitar to walk from the bed to the bathroom. Prince was the same way. Making music was his way of being in the world.”

Rogers recalls an artist who was enormously professional and respectful, quite unlike the sex fiend that was portrayed in the media. “He understood that an artist is a canvas for us to project our own desires and motives on to,” she says. “He was being the bold male that a lot of men wish they could be but society wouldn’t allow them to; he was being the hyper-confident male that a lot of women wish would find them attractive. He was letting us see this almost comic-book hero version of himself, so the real man could hide: a quiet, respectful, polite working man. I never heard him use profanity; he was not lecherous. He was personally conservative, I never even saw a Playboy magazine around the house. It used to make me sad that the impression in the 80s was that Michael Jackson was the safe one you could let your daughter go on a date with, but that you wouldn’t dare trust your daughter around Prince.”

Their work together got Rogers known and she scored a series of other high-profile jobs in a male-dominated industry. “Of course there was sexism, but it worked to my advantage,” she says. “They thought: you’re a woman, you’ve gotta be something special. It worked to my disadvantage, too; I’m sure I did miss out on work. But I wasn’t aware of the jobs I was never up for.”

As well as David Byrne (“like Prince, a beautiful combination of true artist and smart businessman”) she worked with Geggy Tah, a duo consisting of her then-boyfriend, Tommy Jordan, and Greg Kurstin, who won four Grammys this year for his work with Adele. They taught her to “push sound around the way a painter would push paint around on canvas. Picasso can draw a woman and put both eyes on the side of her face and we get it. Likewise, with sound, it doesn’t have to sound exactly like a piano – it needs to be the idea of a piano.” She ended up producing the multi-platinum Barenaked Ladies album Stunt in 1998 – its hit single One Week is a zany showcase of Rogers’ skill – and she used the substantial royalties to pay off her mortgage, quit the industry and take her PhD.

She now teaches production, but also psychoacoustics and music cognition. “It’s about the way the brain processes sound, which is great for sound engineers of the future,” she says. “Early painters would take anatomy classes to learn what a muscle is doing when you make a fist; sound designers should be taking psychology classes to learn about auditory processing beyond the level of the ear.” Rogers, the high-school dropout, spends the next 10 minutes happily chattering about research into neuroaesthetics, child behaviour and synchronicity.

She admits that she listens to less pop these days: “The complexity tends to be extra-musical today – Lady Gaga’s music is not remarkably innovative, but she is.” But she casts her mind feverishly around the music she loves: Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, the Isley Brothers. “I’m just a freak for music. It creates a pattern of neural activity that my particular physiology says yeah, this feels good. It’s scratching an itch; it’s ecstasy.”

Susan Rogers appears at Ableton Loop, Berlin, 10–12 November. My Name is Prince: The Official Exhibition is at the O2, London, from 27 October

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion