In August 1913 the children’s writer Eleanor Farjeon visited the poet Edward Thomas and his family at their home near the South Downs. On their first walk together, Thomas’s 11-year-old daughter Bronwen realised that the city-dwelling Farjeon knew few of the names of the wild flowers that flourished in the surrounding landscape. “My ignorance,” Farjeon recalled later, “horrified her.”

Remedial work was promptly set. Bronwen gathered a hundred different flowers and plants, taught Farjeon their names (“agrimony, mouse-eared-hawkweed, bird’s-foot trefoil … ”), and the next day sat her down “to a neatly ruled examination paper, with the numbered specimens laid out in precise order on the table”. Farjeon was given an hour to complete the test: “60 for a Pass, 70 for Honours.” Her memory was sharp and she topped 90: “Bronwen was proud of me.” Those flower names would later blossom in Farjeon’s books for children, which are twined through with natural lore, notably her chalkland fairy fable, Elsie Piddock Skips in Her Sleep (1937) and her Martin Pippin stories.

Nearly a century later, Cambridge researchers seeking to “quantify children’s knowledge of nature” surveyed a cohort of four- to 11-year-old children in Britain. The researchers made a set of 100 picture cards, each showing a common species of British plant or wildlife, including adder, bluebell, heron, otter, puffin and wren. They also made a set of 100 picture cards, each showing a “common species” of Pokémon character, including Arbok, Beedrill, Hitmonchan, Omanyte, Psyduck and Wigglytuff.

The children were then shown a sample of cards from the two sets, and asked to identify the species for each card. The results were striking. Children aged eight and over were “substantially better” at identifying Pokémon “species” than “organisms such as oak trees or badgers”: around 80% accuracy for Pokémon, but less than 50% for real species. For weasel read Weedle, for badger read Bulbasaur – and this was before the launch of Pokémon Go.

The researchers published their paper in Science. Their conclusions were unusually forthright – and tinged by hope and worry. “Young children clearly have tremendous capacity for learning about creatures (whether natural or manmade),” they wrote, but they are presently “more inspired by synthetic subjects” than by “living creatures”. They pointed to evidence linking “loss of knowledge about the natural world to growing isolation from it”. We need, the paper concluded, “to re-establish children’s links with nature if we are to win over the hearts and minds of the next generation”, for “we love what we know … What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never seen a wren”?

❦

My first response on reading the “Pokémon paper”, as I have come to think of it, was dismay. My second was a wish to write a book for children that might conjure with the magic of “living creatures” rather than “synthetic subjects”. And my third was puzzlement. What had happened to the names and knowledge of nearby nature in the lives and reading of British children? Could they really have dwindled towards a vanishing point?

Subsequent research has confirmed the Pokémon paper’s broad findings. In a 2008 National Trust survey, only a third of eight- to 11-year-olds could identify a magpie, though nine out of 10 could name a Dalek. A 2017 RSPB “Birdwatch” survey smartly shifted the focus, assessing nature knowledge in parents rather than children. Of 2,000 adults, half couldn’t identify a house sparrow, a quarter didn’t know a blue tit or a starling, and a fifth thought a red kite wasn’t a bird – but nine out of 10 said they wanted children to learn about common British wildlife. A 2017 Wildlife Trusts survey found a third of adults unable to identify a barn owl, three-quarters unable to identify an ash tree – and two-thirds feeling that they had “lost touch with nature”.

The hunger is there but the knowledge is not. Where have these lost names gone, and does their vanishing matter? If so, how might we invigorate what anthropologist Beth Povinelli calls “a literacy of nature” in ourselves and our children? Was there ever a time when such a literacy existed? We read the results of these surveys, perhaps, with a mixture of consternation and insecurity. My own children can name a moorhen but not a collared dove, a blackbird but not a starling. They know oak but not hawthorn, beech but not ash. They like to recall the time in a wood when I confidently identified – from 10 yards away – a reddish object as a fly agaric toadstool. On closer inspection it turned out to be a discarded slice of water melon (I blamed my glasses). I know I would have hopelessly failed Bronwen’s flower test, despite living on chalk myself and loving the chalkland flora.

For a decade or so now I have been fascinated by the relationships of naming, knowing and nature, writing a book on the subject called Landmarks in 2015. In the past few years I have become especially interested by these questions as they bear on contemporary childhood – and how they feature in what we uneasily call “children’s literature”, but which I prefer to think of as “literature read by children”, in a wish to avoid limiting or patronising the powers of that extraordinary, diverse body of work.

I am unconvinced that children need names to need nature. The last chapter of Landmarks was entitled “Childish”. There, inspired by the work of an early years specialist called Deb Wilenski, I wrote about the “fantastical travelling” of a class of four- and five-year-old children in Hinchingbrooke Country Park, north Cambridgeshire. Each Monday for three months they explored the park, mapping it through their stories and drawings. I was fascinated by how the children wove words, images and actions together in their inhabitation of this modest landscape (bounded by a dual carriageway and a hospital car park). Given the chance, children will new-mint stories for nature and coin gleaming names for it. Given the chance, they will meet the living world eagerly with their bodies and minds, touching and eating and dreaming it: no Linnaeus necessary.

But I also believe that names matter, and that the ways we address the natural world can actively form our imaginative and ethical relations with it. As George Monbiot wrote recently, calling for a “new language” to vivify conservation, “words possess a remarkable power to shape our perceptions”. Without names to give it detail, the natural world can quickly blur into a generalised wash of green – a disposable backdrop or wallpaper. The right names, well used, can act as portals – “hollowings”, in Robert Holdstock’s term – into the more-than-human world of bird, animal, tree and insect. Good names open on to mystery, grow knowledge and summon wonder. And wonder is an essential survival skill for the Anthropocene.

Clearly the lack of natural literacy – especially of nearby nature – is involved with the major structural changes that have occurred in the experience of minority-world childhood. Online culture has boomed and screen time has soared. In Britain, the “roaming range” (the area within which children are permitted to play unsupervised) has shrunk by more than 90% in 40 years. Traffic growth, the pressures of school work, parental fears and the decrease of available green space have all helped close down wild play and the knowledge it brings. “The children out in the woods, out in the fields,” said Chris Packham in 2012, “enjoying nature on their own – they’re extinct”. Meanwhile, childhood wellbeing declines, with obesity rates rising and mental health dipping. The headline of a 2016 report (sponsored, notably, by Persil) was that British children “spend less time outdoors than prisoners”: climbing walls, not trees.

Such buttonholing headlines disguise a complex picture, though. Access to nature is hugely unevenly distributed across the population, with class, income and ethnicity playing strong determining roles. Within “nature deficit” discourse, “tech” is too often simplistically opposed to “nature”, though it can act as accomplice rather than antagonist, and a lost golden age of barefoot childhood is too often presumed. Shocking headlines also occlude the hopeful signs and good work that are, to me at least, presently visible in Britain and beyond.

In his influential book Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv suggests that both adults and children have increasingly come to “regard nature as something to watch, to consume, to wear: to ignore”. Inevitably, such a shift – if it is a shift, rather than a new edition of an old problem – has consequences for imaginative territories as well as real ones. As children “abandon the sandlots and creekbeds, the alleys and woodlands”, asks Michael Chabon in his essay “The Wilderness of Childhood”, “what will become of the world of stories, of literature itself?”

One answer to Chabon’s question might be found in the data sets provided by the annual 500 Words story competition, run by the BBC and Oxford University Press. This glorious story fest is open to five- to 13-year-olds, and typically attracts more than 120,000 entries, supplying an annual corpus of well over 50m words. Taken together, the stories offered remarkable insights into the communal imagination and vocabulary of Britain’s children. Plots and characters can be seen emerging and fading. It’s possible to drill down in the data to specific lexical choices, tracking the rise and fall of single words.

In the 2017 stories, unsurprisingly, the word “Trump” starred, as well as a rich broth of variants including Trumpelstiltskin (respect!) and Trumpedo. In 2015 the most frequent characters were Wayne Rooney, Snow White, Adolf Hitler, Lionel Messi and Cinderella. “Oak” was the commonest natural term that year, used encouragingly often (3,975 usages). Down at the lower end, heading for disappearance, were “acorn” (293), “buttercup” (168), “blackbird” (167) and “conker” (155). One of the two most popular plots was achieving sudden internet fame after posting a YouTube video. As OUP noted when crowning “hashtag” as the 2015 Children’s Word of the Year, “new technology [is] increasingly at the centre of children’s lives”.

Technology is miraculous, but – and – so too is the living world, including the everyday nature with which we share our everyday lives. And this aspect of the world’s wonder seems presently at the margins of many children’s experience, speech and stories.

❦

Nature, naming and dreaming are all tangled together in perhaps the most famous childhood reading scene in English literature. Jane Eyre is 10, and on the novel’s opening page she has retreated to read on the “window seat”, screened off by a heavy red curtain from the rest of the house. Seated cross-legged, she relishes the “double retirement” of her situation: behind a curtain and within a book. The book is Bewick’s History of British Birds, in which Thomas Bewick’s woodcuts of bird species are accompanied by name details and explanatory notes. As Jane turns the pages, her mind is set wandering: “Each picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting.” She imagines herself northwards, up into the white wastes of the Arctic, borne there on the wings of words and woodcut. “I feared,” she says wonderfully, “nothing but interruption.”

Looking back, I see that many of my own “window seat” books – the ones I read as a child fearing only interruption – shared preoccupations with names and nature. I still owe my (wobbly) knowledge of knapweed and sweet pea to Cicely Mary Barker’s Flower Fairies. Arthur Ransome’s young citizen scientists in Coot Club inspired in me the wish, though not the application, to become a teenage naturalist. I also devoured stories of survivalism, especially BB’s Brendon Chase, in which three brothers live wild in an English forest for eight months, making their camp in an ancient oak.

By far the most powerful books, though, were those in which nature mingled with the supernatural. For me these included John Masefield’s The Box of Delights and The Midnight Folk; TH White’s The Sword in the Stone; the novels of Alan Garner, especially The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Owl Service; Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy; Susan Cooper’s astonishing The Dark Is Rising series; and Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood and Lavondyss. These novels all took deep root in me as a child. Thirty-odd years on, they continue profoundly to shape my fascinations as a writer with deep place and deep time, with wildness, power and the more-than-human world.

Questions of naming and nature return repeatedly in these books. On Le Guin’s archipelago of Earthsea, magic requires knowing “true names” in the Old Speech, the language spoken by dragons and gods. Early on the young wizard Ged realises that to name the natural world is to gain aspects of its power:

When he found that the wild falcons stooped down to him from the wind when he summoned them by name, lighting with a thunder of wings on his wrist […] he hungered to know more such names […] the name of the sparrowhawk and the osprey and the eagle.

Ged learns, though, that on Earthsea you must be careful of what you utter, because there names bind and “cannot be unsaid”. Power has to be used in “balance”, the vital principle of Earthsea’s thaumocracy.

In Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising (1973) – truly a title for our times – knowing the “real names” of things is a form of defensive strength. Will Stanton, the novel’s boy hero, is saved from the Dark’s first assault by standing on a path known truly as “Oldway Lane”, and because his guardian, the magus Merriman, knows “the real name” of their foe. “The only way to disarm one of the creatures of the Dark,” Merriman tells Will, “is to call him or her by his real name.”

And to Tallis – the mesmerising 13-year-old at the heart of Holdstock’s Lavondyss – what adults dismissively call her “name game” is of utter importance. To find her way into the forest of Ryhope that holds her lost brother, Tallis must intuit the “secret names” of each part of the landscape around it: “She had not known, until now, that every field, every tree, every stream had a secret name.” Her grandfather, on the eve of his death, writes Tallis an urgent letter. “The naming of the land is important,” he tells her there, “it conceals and contains great truths. I urge you to listen to the names when they whisper.”

All of these books practise magical acts of natural naming. Occasionally in them, naming is taming: the enforced subjugation of a natural other. Mostly, though, naming enables adventures into the mysterious life worlds of different creatures, even different kinds of matter: Wart becoming trout and falcon in The Sword in the Stone, for instance, or Ged becoming hawk in Earthsea, or Tallis slipping between epochs and species via the “hollowings” she opens in Lavondyss – until at last she is absorbed into the sap and bark of the old wildwood itself.

Such naming events – which embrace mystery rather than assert mastery – might remind us of the contrasting meanings of our verb “to identify”. In its taxonomic sense, it means “to recognise as belonging to a particular category or kind”. Used thus, it is a verb that holds subject and object in hierarchical distance. The verb has a transformative sense, though, where “to identify” is “to feel oneself to be, or to become, closely associated with or part of an other” (OED). This is the identification of which John Keats wrote in his letter to Benjamin Bailey of 1817: “If a sparrow come before my window, I take part in its existence and pick about the gravel.”

Two years and a summer ago I began work with the artist Jackie Morris on a book called The Lost Words: A Spell-Book, about the magic of naming and nature. When we began, we knew only that we wanted to make a modern-day spell-book for the natural world – a book that might go some small way towards conjuring back the words, names and species that were being lost. We wanted to celebrate the “identifications” made possible by names that are, as Observer columnist Henry Porter put it, part of “the plain euphonious vocabulary of the natural world – and do not simply label an object but in some mysterious and beautiful way become part of it”.

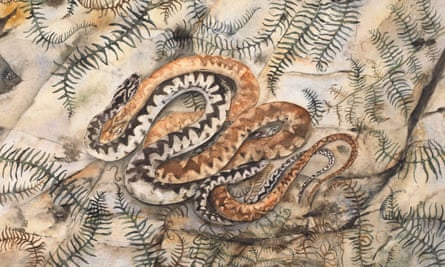

So Jackie and I chose 20 common names of 20 common species of creature and plant. Our choices formed a crooked almost-A-to-Z, from acorn and adder through bluebell, conker and kingfisher, to weasel, willow and wren. For each name I wrote a summoning spell, structured as an acrostic, to be read aloud by child to grown-up, grown-up to child, or even grown-up to grown-up. The act of reading out – of spell-speaking – was also an act of conjuring back.

Because I am certainly not a poet, and do not want to be mistaken for thinking I am one, I always imagined my texts as “spells” or “charms” rather than “poems”. I wrote them to be spoken aloud, and often I wrote them by speaking them aloud – sounding them out while walking or waiting, seeing if they would stick in my mind as chants before putting them down on paper. The otter-spell slipped into my skull while I was walking over the Cairngorms with my father. The willow-spell arrived on the towpath of the River Lea, tramping the unglamorous bank-miles between Broxbourne and Tottenham Hale. The first line of the newt-spell came while I was in the checkout queue at Sainsbury’s.

I sent each drafted naming-spell to Jackie with the same accompanying note: “To be read aloud.” I needed Jackie to test them for what Seamus Heaney called language’s “palp and heft” – its thickening by rhyme and texturing by rhythm. I wanted to write spells that, even if they were not fully understood by their readers, might (Heaney again) “weave a gauze of sound” around them.

Young children meet language sensuously as well as semantically. They embrace what Francis Spufford in The Child that Books Built calls the “gloriously embedded” aspects of language: “Its texture, its timbre, its grain, its music.” These are also the aspects that have always been central to spells and incantations – for such utterances originated in oral cultures where gestures and speech, rather than the written word, were executive.

In many of the spells I found myself writing about shape-shifting: the “partaking of existence” of which Keats spoke, and at which children are such natural geniuses. Thus the last line of the “otter-spell”:

Run to the riverbank, otter-dreamer, slip your skin and change your matter, pour your outer being into otter – and enter now as otter without falter into water.

Elsewhere I tried, futilely, to catch at what Hopkins called the “thisness” of each creature; the swiftness of wren-flight in the first line of the “wren-spell”, for instance:

When wren whirrs from stone to furze the air around her slows, for wren is quick so quick she blurs the air through which she flows.

Nature isn’t always wondrous. Often it’s absurd, violent or vile. Ravens rip the eyeballs out of living sheep stranded in snowdrifts. Skuas half-drown gannets and then eat their vomit. I wanted to allow certain species their brutality or comedy – and others their unsettling, alien otherness. In the “willow-spell”, human voices beg to be taught to speak willow:

Willow, when the wind blows so your branches billow, will you whisper while we listen so we learn what words your long leaves loosen?

But the willows soundly reject their entreaties:

We will never whisper to you, listeners, and even if you learn to utter alder, elder, poplar, aspen, you will never know a word of willow – for we are willow and you are not.

While I wrote, Jackie painted. I had the easy job: 20 spells to cast. Jackie had hundreds of paintings to create. She painted for a year and a half, working seven-day weeks for most of the final six months. For each name she first painted its absence or lostness. Then – on the facing page of my spell – came the conjured-back creature or plant in the form of an “icon”, set against a shimmering background of gold leaf. Finally, she painted a double-page spread showing each species back in the landscape of which it was intricately part: wren whirring through furze, acorns in an owl-haunted oak-wood.

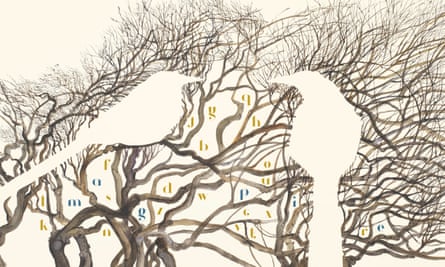

The absences were hardest. How to paint what isn’t there? Jackie drew the empty silhouette of a wren in 18 pen strokes, miraculously catching its teleport-quickness, its jaunty-jenny pose. She painted a blue ripple under willow leaves where a kingfisher should have broken a stream’s surface; a single heron feather rocking down through air. On these “absence” pages, too, Jackie hid single letters that – when sought and found by children – would spell out the lost word. So the book grew and grew and grew – until it was 128 pages long and a foot-and-a-half high: a proper grimoire.

We should be unsurprised that nature’s names are vanishing from children’s mouths and minds’ eyes, for nature itself is vanishing. We are presently living through the sixth great extinction – a speed and scale of planetary biodiversity loss not seen since the Cretaceous. At a local level, this expresses itself in what Michael McCarthy memorably calls “the great thinning”. The 2016 State of Nature report found Britain to be “among the most nature-depleted countries in the world”, with 53% of British species in decline – among them barn owls, newts, sparrows and starlings.

As nature thins, so does our memory of it. Shifting baseline syndrome flattens out the losses; each generation grows into ease with its new normal for nature. The grim end-point of this thinning is foreseen in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, where common names survive but the common species to which they refer are all extinct. Names in that novel are spoken hopelessly, shaken like rattles filled with ash.

“Reconnect with nature” is the mantra for fixing this awful decline – as if we could just plug the toaster back into its socket and get right on back to lightly browning bread. We load the cant-word “connection” with responsibility, but rarely examine what it means philosophically or practically. An exception to this is the RSPB’s 2013 Connecting with Nature report, based on a three-year research project. Sensibly, the report recognised “nature deficit” as a complex problem, strongly inflected by socioeconomic and cultural factors. Dismayingly, it found only one in five British children to be “positively connected to nature”. Hopefully, it emphasised “nature connection” as not only a “conservation” issue, but also one closely involved with education, physical health, emotional wellbeing and future attainment: what’s good for nature is also good for the child.

❦

Nature deficit needs structural and political fixes. Hearteningly, hundreds of organisations – from Earth Force Education to the John Muir award and the Forest Schools Network – are striving to close the gap between childhood and nature, including working with schools to get more children learning outdoors, regularly. Most of these organisations specifically aim to help children at risk of social exclusion, or who are otherwise unlikely to reach green places. A proportion of proceeds from each copy of The Lost Words is being given to one such organisation, Action For Conservation – a young charity with the mission of empowering young people to take action on behalf of the natural world.

Nature deficit also needs cultural and creative responses. We are “blessed with a wealth of nature and a wealth of language,” concluded Monbiot in his essay on natural naming, “[so] let us bring them together and use one to defend the other.” Just so – and in the work of increasing numbers of contemporary writers for children, nature and language tangle wonderfully. I think here, among many others, of SF Said’s Varjak Paw books, Terry Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching novels (where natural knowledge is both praised and parodied), Michelle Paver’s Chronicles of Ancient Darkness series, Katherine Rundell’s The Wolf Wilder and The Explorers, the novels of Abi Elphinstone and Cressida Cowell, and Piers Torday’s The Dark Wild and The Last Wild. We need all the wildness we can get in the books that our children read, and more. Will it do any good? Only its readers can tell us that.

In her classic study of children’s literature, Boys and Girls Forever, Alison Lurie recalls moving from the city to the country and becoming aware of the “impenetrable thicket of blackberry briars and skunk cabbage” beyond the garden fence. “No longer a rationalist,” Lurie remembered:

I began to believe in what my storybooks said. Suddenly I saw the landscape as full of mystery and possibility – as essentially alive. For me, and I think for most children who have really known it … nature seemed both powerful and sentient.

This, it seems to me, is what nature must best be to children: something “alive, powerful and sentient”, rather than something that can be, in Richard Louv’s terms, “watched, consumed, ignored”. The difference is akin to that between anthropomorphism and animism: in the first, we convert the more-than-human world into an image of ourselves; in the second, we lean a little into its complexity and mystery.

The bird which became the guiding, gilding spirit of The Lost Words is the goldfinch. Goldfinches flit across its cover and gleam from its pages. They are present in part as a sign of hope, for those bright birds represent a rare conservation success story in Britain, their numbers having surged by almost 50% over the past 10 years. They are there, too, because the collective noun for goldfinch is a “charm” – a word which also means “the chanting or recitation of a verse supposed to possess magic power” and “the blended singing of many birds, or children”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion