The adverse impact of anti-trafficking laws and policies on sex workers rights has been documented extensively for the last decade. Despite calls for change from sex workers, human rights activists, academics and a range of other actors, states around the world have been reluctant and slow to respond. Some analysts emphasise that the states’ use of anti-trafficking laws to limit immigration is largely responsible for this reluctance. I further add that the analysis of the historical development of contemporary anti-trafficking policies is crucial to understanding the escalating criminalisation and stigmatisation of sex workers, migrants and other vulnerable populations. I argue that any legal framework centred on ‘crime’, rather than on rights and the structural causes of social ills, is bound to disproportionately and systematically impact the poor and vulnerable.

Saving women from ‘white slavery’: the roots of the anti-trafficking

The roots of contemporary anti-trafficking laws can be firmly located in the prostitution-abolitionist ideology of the late 19th century; a period during which trafficking was also referred to as ‘white slavery’. The white slavery campaigns portrayed a world filled with sexual danger for young white women, seduced and exploited by sinister dark men. Thus these campaigns were driven by xenophobia, racism and classism at the peak of British imperialism.

By the mid-1800s anti-solicitation laws (targeting prostitutes) had become a staple of urban codes. Prostitution-abolitionists joined other anti-vice crusaders in the 1800s, introducing a new strategy. As a precursor to the legislative approach taken by Sweden and other countries today, the prostitution abolitionists held that women were forced into prostitution, and were therefore victims rather than criminals. They also opposed legal prostitution, objecting to[ “…the double standard of sexual morality reinforced by the policing and control of women's bodies [and] … fought to expand the definition of trafficking to include third party involvement]8, which they argued should be penalised or criminalised.” Then, as today, this legislative and campaign strategy was ostensibly offered in sympathy. However, the criminalisation of third parties drove commercial sex underground and resulted in extreme and dangerous isolation of sex workers, because third parties could include landlords, domestic help, family members, brothel owners and even support among sex workers themselves.

The closure of the brothels also coincided with a rise in property values. The legal status of prostitution was thus subject to the politics of land development, an on-going element of prostitution repression. In the US, marginalised urban populations from immigrants to newly emancipated African Americans were targeted under such statutes as the 1910 Mann Act or White Slave Traffic Act. This statute established a central database of ‘known prostitutes’ and led to the formation of the FBI, in a stark example of how anti-trafficking policies widen police powers. Such repression and criminalisation of most aspects of prostitution soon spread around the globe. This firmly re-located prostitution deep within the underground economy, exacerbating and causing vulnerability. The murder rate of sex workers has since increased steadily, along with police abuse against adults and youth.

The criminalisation of third parties and the definition of prostitution as an inherent ‘evil’ was further cemented at the global level by the 1949 UN Convention on the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. As Kamala Kempadoo argued in her paper “Trafficking for the Global Market: State and Corporate Terror,” anxiety over the trafficking-prostitution nexus gained even more momentum following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc:

It would appear that the appearance of women from the former USSR countries in Western European sex industries, was a main reason for European governments to pay attention to the problem of trafficking. In many ways, this focus echoes the late nineteenth - early twentieth century crusade...It would seem yet again, that attention for the lives of white women … has propelled international action.

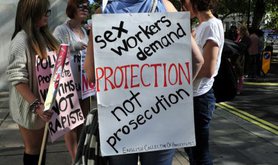

The fight for sex workers’ rights

In the late 70s, the sex workers’ rights movement radically suggested that sex workers were a class of workers wholly eligible for human, civil and labour rights. This led to the organisation of international conventions for sex workers and human rights activists, beginning with the International Committee for Prostitutes’ Rights in the 80s. The analysis offered by these groups reflected development, social justice and harm reduction theory. There was increasing recognition of the flaws of prostitution-abolitionist strategies at these conferences and within academia, as well as calls for the self-representation of sex workers as put forth by the Network of Sex Work Projects.

In the 90s, in response to the growing attention to migration issues, and informed by sex worker rights activism, a collaboration of rights-based groups created the Human Rights Standards for Treatment of Trafficked Persons. Their intention was to advocate for an anti-trafficking protocol that targeted the abuse of all workers—including sex workers—primarily in the context of migration. The disagreements between this collaborative group and the prostitution abolitionists were laid bare in the late 90s, when these diverse factions were invited to participate in drafting the new UN Trafficking Protocol. A battle ensued.

It was apparent that prostitution abolitionists had no interest in including forced labour in the UN Trafficking Protocol. Rather, they insisted that the Protocol be used as a tool to abolish prostitution. In the compromise reached at the end, the new UN Trafficking Protocol referred to labour abuses involving the use of force, fraud, coercion, etc. for the purpose of exploitation. More significantly, the Protocol specifically chose not to define ‘sexual exploitation’. This left individual states to define it as they saw fit, equating prostitution with sexual exploitation or defining sexual exploitation as abuse within prostitution. In this way the Protocol could be interpreted as supporting both proponents of legal prostitution and those seeking its abolishment.

These strategies within the UN Protocol have largely failed sex workers as well as migrants and trafficked persons. In addition, while the included human rights protections are optional, the criminalisation and border controls are mandatory. In consequence, the predominantly criminal justice response primarily aims to stop commercial sex through immigration raids and arrests, yet is coupled with limited support for a wide range of victims. Thus, as stated by Marjan Wijers, “This focus on the purity and victimhood of women, coupled with the protection of national borders, not only impedes any serious effort to address the true human rights abuses we are confronted with... but actually causes harm to real people.”

Under pressure from prostitution abolitionist coalitions, many countries have now enacted domestic anti-trafficking laws that focus exclusively on prostitution, retreating to strategies of the earlier centuries. In the United States, the prostitution abolitionist lobby, in alliance with religious fundamentalists, strenuously lobbied for all sex workers to be considered victims of trafficking to foreclose the option for legal prostitution and labour rights for those involved. These groups also recommended a bifurcated definition of trafficking, one that separates ‘sex trafficking’ from other forms of labour trafficking. The US Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which partially reflects this proposal, defines sex trafficking as “the recruitment, harbouring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act.” No condition of force, fraud or abuse is stipulated. Although ‘sex trafficking’ is not included in US criminal codes, the TVPA certainly paves the way for that possibility.

The focus of enforcement in the United States has primarily been on suppressing commercial sex, rather than on addressing abuses within the sex trades. These repressive ideologies are also actively promoted and exported through channels such as the ‘Anti-Prostitution Loyalty Oath,’ which requires beneficiaries of US aid money to guarantee their opposition to legal prostitution. US domestic funding followed a similar direction, rendering sex worker organisations ineligible for funding. Sex workers were also excluded from further participation in policy making in both systematic and and informal ways.

State of play

The current neo-abolitionist movement has expanded its strategies to include the ‘Nordic model’ of prostitution repression. Clients are now included in the long list of targets of criminalisation, escalating the isolation of sex workers. Although abolitionist philosophy is ostensibly opposed to criminalisation of sex workers, internationally such campaigns have been launched where prostitution is legal, or as a means to further criminalise the sex industries, rather than as a means to decriminalise sex workers. It is this crime-based approach that also promotes tighter border controls, as well as the escalating punishment and targeting of migrants, youth and people of colour. These ‘solutions’ exacerbate violence and vulnerability in many populations, just as the criminalisation of brothels in the 1800s resulted in a century of isolation and increased violence against sex workers.

Sex workers have long explained that one of the many conditions needed to prevent the abuses often conflated as ‘trafficking’ is the decriminalisation of sex work. This principle is supported by Human Rights Watch the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, the United Nations Development Programme, UN Women and UNAIDS, among a growing list of international bodies.

Clearly, some results of anti-trafficking policies have been positive for those individuals found to qualify for protections, affording them specific visas and settlements among other humanitarian advances. At the same time, substantial evidence of adverse effects has been found following research carried out by the Global Alliance against Traffic in Women. From a rights based perspective, any legal framework that centres on ‘crime’ rather than on rights and the structural causes for social ills is bound to disproportionately and systematically impact the poor and vulnerable. Meanwhile, the double-edged sword of anti-trafficking places vulnerable populations in competition for justice, because those qualified as trafficked persons may obtain recourse from the same systems that punish other, equally vulnerable individuals.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.