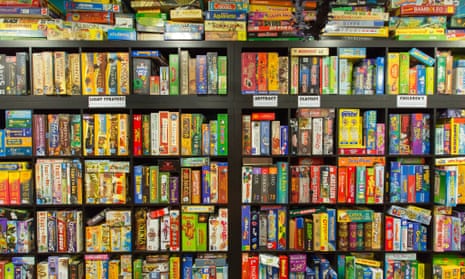

Tell most people that you’re a “gamer” nowadays and they’ll subconsciously add the prefix “video”. But while digital games are grudgingly acknowledged as part of the entertainment mainstream, the past decade has also seen unexpected growth in an industry that many assumed would become redundant in the era of screens: tabletop board games.

Sales are still dwarfed by the latest PC and console blockbusters, but the past four years have seen board game purchases rise by between 25% and 40% annually. Thousands of new titles are released each year, and the top games sell millions of copies.

To successive generations raised on the Mega Drive, PlayStation and iPhone, the concept of sitting around a table rolling dice and moving pieces may seem positively archaic. But beyond mass-market titles like Monopoly and Guess Who, a community of independent designers and publishers has been steadily producing innovative, exciting and beautiful games offering experiences beyond even those of the most sophisticated gaming hardware.

Ugg-Tect, for instance, challenges players to build a series of 3D structures while communicating only in primitive cave-man grunts. Make a mistake and you’ll receive a smack on the head from one of the inflatable plastic clubs that come with the game – an element of physicality that would be difficult (or at least painful) to replicate with a console controller.

It’s the result of an approach to game design that considers the creation of shared social experiences to be every bit as important as writing rules or designing physical components, and while Ugg-Tect plays for laughs, there are thousands of other games which tackle a broad range of subjects from monster-slaying fantasy to serious social issues.

Pandemic casts players as a team of medics attempting to rid the planet of four deadly and highlyinfectious diseases. Dead of Winter challenges a group of survivors to stay alive in a world overrun by flesh-eating zombies. Freedom – The Underground Railroad examines the history of the US abolitionist movement, with players working to shelter runaway slaves while simultaneously fighting to end the practice of slavery by political means.

A golden age of gaming

Many industry figures point to the internet as a key factor in the growth of tabletop gaming. The rise of smartphones and tablets has given players an inexpensive way to try digital versions of board games, and many go on to buy physical copies as well.

Online retailers have made games far more easily available than in the past, when many could only be procured from a small number of specialist shops. At the same time, the power of blogs, online video and social networks has created word-of-mouth buzz for an industry that, until recently, has been largely ignored by mainstream, non-gaming media.

But players and designers are keen to suggest another reason for the hobby’s resurgence. Games are simply getting better. Publishers are turning out products with elegant mechanics and impressive artwork as fast as their customers can snap them up. Board games are going through a golden age.

Scott Nicholson is a game designer and the director of the Because Play Matters game lab at Syracuse University’s school of information studies. He argues that board gaming’s boom is the result of a collision between two distinct traditions of game design.

“In the past there have been big differences between European and American approaches to making games,” he says. “American games would typically have players engage with one another through aggression. European games tended to use more indirect conflict – so rather than just fighting one another, we might be competing for the same pool of resources, or trying to accomplish the same goal most effectively.”

Nicholson points to one game in particular as an influential example of the European design philosophy.

Designed by German dental technician Klaus Teuber, The Settlers of Catan has sold 18m copies since its release in 1995. Players compete to colonise an island, building settlements, laying down roads and trading goods to build the most powerful faction.

“Catan made people aware that games could be about things other than moving along a track or destroying each other in combat,” says Nicholson. “The element of trading means you’re involved in the game at all times – even when it isn’t your turn, you’re always engaged and you’re always paying attention. There’s no frustrating down time, which was a big deal when the game first came out.

“It influenced a lot of games that came afterwards, and over the last 10 years or so the two design spaces have collided. It used to be that American games would prioritise story at the expense of mechanics and European games would have smooth mechanics, but very thin themes; today, with a lot of games, it’s hard to claim that they’re one thing or the other.”

Games for everyone

The success of Settlers of Catan brought a huge number of new players to board gaming, and the rapidly expanding marketplace gave rise to new publishers and designers who brought a wave of creativity and innovation to the hobby.

Among them was Susan McKinley Ross, a toy designer who hosted a monthly get-together at her home where she and a group of friends would play mainly European-style games. But it was a more familiar mainstream title that inspired McKinley Ross to create a game of her own.

“I was watching two friends who were fantastic Scrabble players, and I realised that the part of the game I liked most was when players could make more than one word with a single move,” she says. “That night I had a dream about a similar game, but one that used shapes and colours instead of letters. As soon as I woke up I started putting a prototype together.”

That idea went on to become Qwirkle – a tile laying game that dispensed with words, letters and even a game board. Players lay square wooden tiles directly on to the table, trying to form lines showing matching shapes or colours.

It’s a straightforward design – far simpler than most of the games McKinley Ross played herself – but it proved popular. Qwirkle initially sold well in the US, but interest in the game spiked when it was awarded the 2011 Spiel des Jahres (Game of the Year) prize – board gaming’s equivalent of an Oscar for best picture.

“I was so excited just to be nominated that it took me about a year to realise I’d won,” says McKinley Ross. “It was just astounding, and it was a huge boost for the game – particularly in Europe where sales just ballooned.”

But while Qwirkle’s creator was delighted with its critical and commercial success, she said she took greater satisfaction in the thought that her game had brought players together. “It’s designed to be a very accessible game – children can play it on a comparable level to adults,” she said.

“I grew up playing board games with my parents and grandparents, so hearing about families playing together at a time when people are increasingly turning to electronic games is a real thrill.”

What the past five years has taught us, however, is that there is ample room for both digital and analogue gaming experiences. The two seemingly very different formats are learning from each other, borrowing ideas and conventions and evolving accordingly. This is a game that every one wins.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion