China’s ‘stolen’ cultural relics: why the numbers just don’t add up

Every year, around the anniversary of the sacking of Beijing’s Summer Palace in 1860, come fresh calls for the return of ‘stolen’ antiquities. A Post Magazine investigation reveals China’s claims are often inaccurate, even grossly inflated

More than 150 years after British and French troops sacked and razed the Summer Palace, in Beijing, the incident is regularly revisited in the Chinese press. Articles usually appear around the October anniversary of the destruction, after yet another announcement of plans to catalogue looted antiquities now overseas, or when Summer Palace items appear at foreign auction houses.

As well as their incomplete and inaccurate descriptions of the palace and its destruction, these stories often contain transparently false accusations against foreign institutions holding collections of Chinese treasures, as well as unsustainable claims of a legal right to them and demands for their uncompensated return.

Even the most outrageously distorted claims often go unrefuted by timid governments and cultural institutions, perhaps for fear of complicating more important diplomatic negotiations or voiding loan arrangements and cultural exchanges.

Museum public relations departments keep curators away from the press and mention of the Summer Palace is omitted from catalogue and cabinet label alike. Requests for a response to the Chinese campaign for repatriation of just about anything Chinese, with its insinuation that even legally purchased items are loot, are answered slowly, if at all.

As a result, it’s easy to conclude that museums, particularly those in the English-speaking world, must indeed have a lot to hide, although just how much is hidden away is itself the subject of considerable distortion. The French are more outspoken about both their possessions and their plans to retain them, yet receive less criticism.

For many years it has been claimed in the mainland Chinese press (as well as the South China Morning Post), with minor variations, that 1.64 million Chinese antiquities reside in 200 museums in 47 foreign countries.

On a 1998 visit to Beijing, Britain’s then prime minister Tony Blair was asked by a local journalist how he could justify the British Museum’s continued possession of 23,000 of these antiquities, a question still being posed when successor David Cameron visited 15 years later.

The China Centre for International Economic Exchanges, a “super think tank” headed by former vice-premier Zeng Peiyan, took up the invitation to ask Cameron questions via his newly created Sina Weibo microblog account.

“When will Britain return the illegally plundered artefacts?” was the inquiry, with the implication that the museum’s entire Chinese collection had been acquired by military force.

By last year, the source for these figures was repeatedly claimed to be “a Unesco study”, although in fact an information pack by the UN’s heritage body on the illicit trafficking of cultural property merely quoted a 2009 article in the magazine Art Antiquity and Law, by author Ji Ling. There is no such Unesco study.

In 2009, the Summer Palace’s then director, Chen Mingjie, claimed that 1.5 million antiquities had been looted in 1860 alone, and that they were in 2,000 museums, 10 times as many as previously suggested. By last year, the China Cultural Relics Academy was estimating that 10 million Chinese items were overseas, including those in private collections.

Among public institutions, London’s British Museum is often said to be the chief culprit, with its holdings now sometimes magically increased tenfold to 230,000 items, all now claimed to be from the Summer Palace. Eventually, the museum meekly responded to Post Magazine, claiming that, among its 23,000-item Chinese collection, purchased from or donated by myriad sources over a long period, just 15 pieces might possibly be of Summer Palace origin.

The French are typically more forthright. When asked in a 2011 interview how many items in Paris’ Château de Fontainebleau collections were from the plundering of the Summer Palace, the then director of patrimony and collections at the French museum, Xavier Salmon, answered immediately and unblushingly, “We think between 600 and 800.”

As the ponderous shutters of Fontainebleau’s Chinese Museum are unbarred and swung open, gleams of gold in the dark interior swell into a display of dazzling magnificence. Jades, porcelains and bronzes jostle for shelf space around a jewel-encrusted golden stupa flanked by two upright elephant tusks. The walls are lined with landscapes in gold and black lacquer, and the ceiling is draped with silk tapestries. The chamber buzzes with beauty, and it is difficult for the eye to know where to rest.

Here, then, is the magnificence that otherwise exists only in the imaginations of those keen to magnify for political purposes the wonders of the now-vanished Summer Palace.

The complex’s decay was already apparent in 1793, when it was visited by Lord Macartney, King George III’s ambassador to the Qianlong emperor. The best of the palaces, wrote Macartney, “is so much out of repair that I already see it will be impossible to reside in it comfortably during the winter”.

The French boxed up the best of the treasures they plundered from the Summer Palace and shipped them to Emperor Napoléon III. The Empress Eugénie is said to have been present in person at the opening of the crates.

She selected items to display in a purpose-built museum, mixing them with gifts from other parts of Asia, purchases from Parisian antiques shops and treasures confiscated from aristocratic families during the French revolution. She commissioned the building of display cabinets inset with Chinese panels and gave pieces of Chinese cloisonné to a master craftsman to incorporate in a vast chandelier that, 150 years on, still glitters overhead.

“She didn’t have an historic or artistic vision for these objects, she had a very personal vision,” said Salmon. “It is she who created this ambience, mixing up techniques and colours in a manner to which her eye responded and which was of the China of her imagination.”

Eugénie’s creation, he firmly asserted, was now part of French patrimony and “to return the objects would be to destroy a little bit of French history”.

But if the items were stolen, is this a sufficient defence?

“The question of plunder in war remains a question with a history as long as that of the planet,” said Salmon. “The history of the world has been regularly marked by these events, and the Chinese with their politics of conquest have also taken objects from their proper culture.”

In fairness, wild claims about the grandeur of the Summer Palace and the quality of the items stored therein began not with the Chinese but with Jesuit missionaries keen to justify the costs of maintaining their mission in the Manchu empire’s capital, and who compared the Summer Palace to Versailles.

There were also conflicting overestimates of the Summer Palace’s size from foreign travellers anxious to impress their readers.

Official descriptions of the now-much-built-over site continue this tradition in order to exaggerate the losses, increase criticism of foreign powers and enhance support for the Communist Party as the only bulwark behind which the Chinese can effectively unite and resist foreign exploitation.

The truth is, the number of surviving Summer Palace antiquities is unknowable, although no expert credits the figure of 1.5 million looted items overseas. There are no records of the palace’s original contents, much was destroyed on site and several eyewitnesses describe extensive looting by both local Chinese and the 2,500 coolies from southern provinces who were aiding the foreign forces (information also omitted from Chinese accounts).

Those forces were welcomed with open arms by Peking shopkeepers and items both with palace provenance and without were purchased and mixed together. Chinese traders in Canton and Hong Kong were willing purchasers of loot from the French troops who passed through on their way home.

The French expeditionary force provided lists of what it had packed, but these contain very little in way of description: “A vase, a vase, a vase,” quoted Salmon, from one of these lists, which makes individual identification impossible.

Furthermore, little in the Summer Palace was unique to its collection and, according to those present, the most easily identifiable items were of foreign manufacture, such as the field guns given by Macartney’s late-18th century embassy and French clocks and watches in such numbers that French looters sold them for pocket money to British soldiers, whose own looting opportunities had been relatively limited.

Chen never contacted the institutions he had accused of holding the largest collections, according to Salmon and other museum officials. Instead, a visit to museums in nine American cities in 2009 was deemed a success for the “discovery” of several previously unknown items. Chen declined to provide details except for those of a single Song-dynasty painting at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which bore 18 seals, including those of the Chun Hua Xuan, a hall in the Summer Palace complex.

At first, the museum claimed difficulty in identifying the painting in question, and gave a carefully anodyne response: “We have many strong connections to cultural institutions in China and look forward to continued collaborations.” It eventually emerged that the painting had been purchased from a Chinese seller within China in December 1913. And while the museum is apparently shy of labelling the painting in English as being of Summer Palace origin, Herd-boys with Water Buffaloes Under Willow Trees can clearly be seen on its website complete with identifying seals.

Chen’s “discovery” could have been made from a comfortable chair anywhere in the world, including Beijing. The painting had not been on public display since 1997, and a museum spokeswoman said in an e-mailed response that she could find no record of Chen’s visit.

In recent years, auctions of Jesuit-made bronze animal heads from the 1860 looting have brought ever more strident demands for their return. There have been futile legal attempts and the intervention of state actors willing to pay any price for national pride. This has driven up bidding for other Summer Palace items to well beyond what the state is willing to pay, leading to claims in Chinese media that prices are “unfair”.

When acquired instead by Chinese nouveaux riches, these pieces sometimes disappear into private collections and remain as invisible to ordinary Chinese as they were in Europe – or were back in 1860. Foreign museums are willing to lend items for exhibition but a willingness to accept them would also suggest acceptance of foreign ownership, and the political campaign has made this impossible, even where antiquities were legally purchased from Chinese sellers. Rather than achieving its aim of acquiring Chinese treasures, the carefully orchestrated brouhaha has put them further out of reach.

Eighteen of his party were murdered but Loch survived to bid successfully for a pair of cloisonné double crane censers. In 2010, these were auctioned again and their Summer Palace connections helped push their sale price to US$16.7 million, a new record for cloisonné and roughly 17 times the value of the entire original British haul.

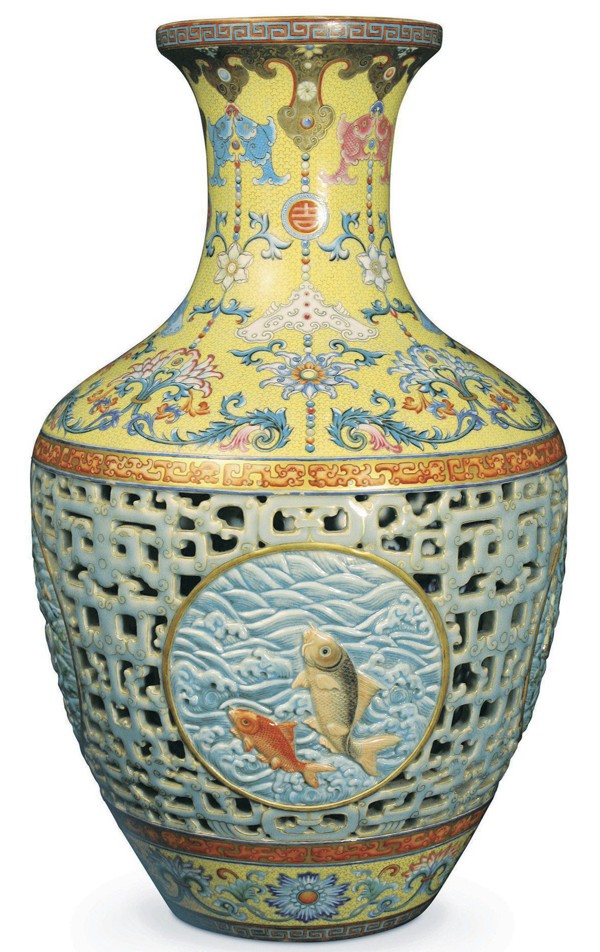

This was not a quirk. A month earlier, a gaudy Qing-dynasty porcelain vase from the Summer Palace had been sold by a small English auction house to a Beijing-based bidder for US$85.9 million, including tax and fees – 50 times its estimate.

While many museums now shy away from discussing the Summer Palace provenance of items in their collections, Chinese cataloguers and foreign auctioneers claim it wherever they can because it adds both political and financial value.

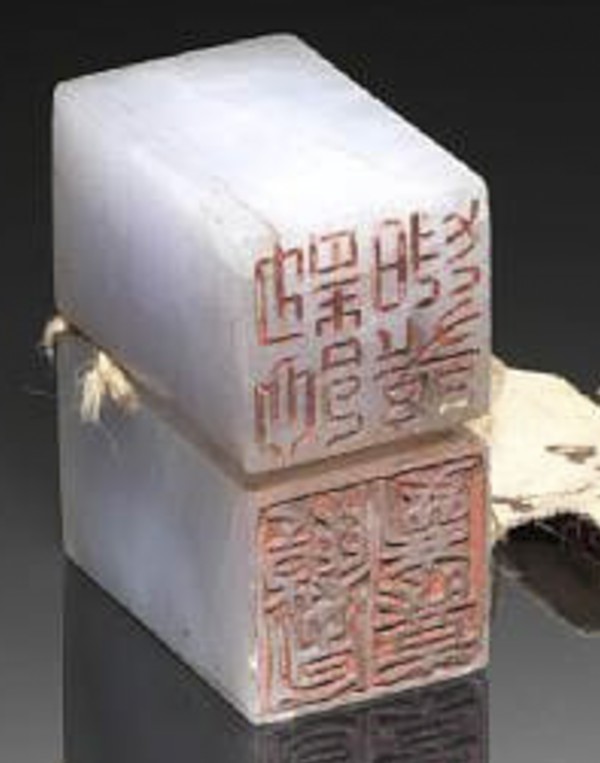

In May 2011, Bonhams promoted the auction of a white jadeite seal sold by the descendants of a 19th-century medical missionary to China, William Lockhart. The auction house sought to add Summer Palace lustre by mentioning the entirely irrelevant “unequivocal support” for British actions shown in Lockhart’s memoirs, and stating that he was “possibly” in Beijing during the sacking.

Lockhart’s concise chapter of history on Anglo-Chinese relations from 1839 to 1860 contains not even a hint that he was at the Summer Palace. He moved to Beijing only in 1861. The price obtained was only double the estimate, suggesting that bidders found Bonhams’ claims no more credible than those of Chen.

In April 2011, complaints about unfair auction prices gave way in the official China Daily to the headline “Asian art market sizzles”. A surprisingly outrage-free article oozed with national pride because there were now Chinese sufficiently wealthy to pay record-breaking sums for Summer Palace jade, cloisonné and ceramics, while still avoiding any suggestion that state interference had increased the need for such deep pockets.

This was finally acknowledged in assorted articles in November last year that quoted Song Xinchao, deputy director of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), as decrying the private purchase of “lost relics”, because “purchasing them will, in a way, confirm the legitimacy of such thefts, and make the prices of these items even higher in the international market”.

As with the inquiries made to the British prime ministers, there was also the implication that all Chinese treasures “lost” overseas must be, in some sense, stolen.

Around the rim of the lens-shaped Taklimakan Desert, signs at cave-temple sites condemn by name the foreign explorers who plundered frescoes, paintings and manuscripts during an Indiana Jones-style archaeological free-for-all in the early 20th century.

At Dunhuang, where sheer cliffs are pitted with hundreds of hand-carved caves dating back as far as 366CE, it is again the British and French who come in for most criticism. In 1907, Britain’s Marc Aurel Stein purchased thousands of documents recently discovered in a hidden library cave. The following year, France’s Paul Pelliot did the same, as did subsequent Russian and Japanese expeditions.

The seller was a Taoist monk, Abbot Wang, the caves’ self-appointed guardian, who had been unable to interest local officials in the documents he had discovered and who wanted funds for the preservation of the caves and their frescoes.

The sums paid by foreigners were large for what local people regarded as useless papers in assorted scripts they could not read, but derisory in terms of their cultural significance. The Chinese authorities now cry foul.

The November 2016 articles, in assorted Chinese media and a paid-for soft-power supplement to The Washington Post, claimed China had triumphed by suppressing a Yokohama International Auction sale of Tang-dynasty frescoes and manuscripts from Dunhuang “stolen by Otani Kozui, a Japanese abbot who was part of expeditions to China between 1902 and 1913”, according to SACH.

Accuracy is once again of little interest here. The records of the exhibitions financed by Otani make it clear he did not travel to Dunhuang in person but those he’d sponsored did purchase the scrolls directly from Abbot Wang.

These Dunhuang manuscripts were catalogued before financial trouble led Otani to sell the remainder of his collection in 1915, but take the Dunhuang items to Lüshun, in Japanese-occupied northeast China. After Japan’s 1945 defeat, these manuscripts ended up in museums in Lüshun and Beijing, except for 49 later discovered in Japan, which are now at the Ryukoku University, in Kyoto, and not for sale.

It is not entirely clear, then, what Yokohama International Auction intended to sell at the suppressed auction, but this is one of the exports of antiquities about which China has least to complain, since almost all are already back in the country.

“[Otani] is often vilified for his acquisition of antiquities, even though his collection was quite modest in comparison to that of Aurel Stein, but he was Japanese and, on top of that, related by marriage to the imperial house, all of which have a very bad resonance with the Chinese public.”

Records of three Otani-sponsored expeditions show that frescoes were acquired not from Dunhuang but from Miran, hundreds of kilometres further west, and these are now in the National Museum of Korea, in Seoul.

“We are not conditioned by guilt,” said a forthright Jacques Giès, when interviewed at the Musée Guimet in Paris in 2011. Giès had spent more than 30 years curating the museum’s magnificent Silk Road displays. “Our duty is to present the best of the Chinese creation, to testify to the excellence of this civilisation, and to let our public have respect for Chinese history and civilisation.”

Indeed, Giès points out that Silk Road studies were a foreign invention. It was the 1890 discovery by a British Indian Army officer of ancient texts on birch bark in an unknown language that sparked multiple arduous desert expeditions to discover more of the same.

It was principally European, Russian, Japanese and American scholars who pieced together the history of the trade routes, deciphering scripts and translating forgotten languages.

“We, who have worked for almost one century on these materials, represent the best of the best of the scholarship in all these countries, and these materials were essential not only for the history of China, but also for all High Asia and the Indian subcontinent,” said Giès.

In other words, there are many other Asian cultures that might lay claim to the Silk Road treasures, including those of the local minority and the Tibetans who controlled Dunhuang for centuries and compelled the local Chinese to wear Tibetan clothing and speak Tibetan.

Of the Otani Dunhuang documents already back in China, it’s the Chinese-language ones that have been taken to Beijing, with those in other languages left tucked away in distant Lüshun.

“History is not made of ‘if’,” said Giès. Due to the French revolution, the most important French royal furniture collections are in England. “But that’s history. I am very grateful because they preserved these pieces which could have been destroyed.”

Dr Frances Wood, formerly head of Chinese collections at the British Library, says she is familiar with that sentiment.

“In private, most Chinese scholars are much happier that the material is in England,” she says. The Dunhuang scrolls remaining in Japan are dwarfed in number by those in the British Library’s collection, purchased by Stein from 1907.

“There are about 7,000 fairly complete scrolls, so they’re reasonably substantial. Six thousand of those are rolls of paper anything from five to 30 feet long, mostly Buddhist. And then when you get towards the other end, they’re very tiny fragments because they’re really the bottom of the sacks.”

No sooner had China begun to open up in the 1970s than Chinese scholars were invited to work on this “Stein debris”, carefully flattening pieces for analysis.

Continuing cooperation by members of the British Library-based International Dunhuang Project has seen thousands of documents from collections around the world digitally photographed and made freely available online. The British Library’s entire Dunhuang collection is now being published in a 150-volume catalogue by the Guangxi Normal University Press.

In private, most Chinese scholars are much happier that the material is in England

In 2014, China drafted an international rule on the return of cultural property – China’s first such effort, reported the China Daily, in November. “The Dunhuang Recommendation has led to more success in China’s efforts since then.”

However, this home-made “international rule” is merely wishful thinking and China has been party to a 1970 Unesco convention on the illicit transfer of stolen cultural property since 1989. It is this that provides a proper legal basis for reclaiming stolen antiquities, but it doesn’t apply to those taken before 1970, and the Dunhuang Recommendation, as the 2014 rule is known, changes nothing.

Yokohama International Auction is registered in Hong Kong and its owner is reportedly a Japanese national of Chinese descent. On its Japanese webpages – although not those in Chinese – the company makes clear that its very purpose is the return of Chinese antiquities to China.

Before being cancelled, the November auction had been won by a Japanese national, but the items were returned to their owner, not passed to China. This was, in fact, the opposite of progress, and nothing to do with any “international rule”.

Threats against foreign auction houses with Chinese connections have been seen before, such as in another quoted example of “more success in China’s efforts”, the 2013 return of two bronze animal heads originally from a fountain in the Summer Palace.

Through the holding company Groupe Artemis, Pinault also owns auction house Christie’s. The heads had appeared in a Christie’s-run auction of the late Yves Saint Laurent’s effects in Paris in 2009, leading SACH to threaten “serious effects” on Christie’s’ future in China. It was widely reported that the company began to experience difficulties with Chinese customs inspections.

Pinault was accompanying then French president François Hollande on a trade visit to China at the time of the announcement of his donation. It may only be coincidence that Christie’s became the first international fine-art auction house to receive a licence to operate independently in China that very same year.

Other claimed Chinese successes concern antiquities stolen recently by Chinese themselves and smuggled overseas, their repatriation subject to existing conventions and not to any newly coined domestic rule. But the Communist Party ensures that only its own version of events is heard domestically, and stories of foreign destruction and looting certainly help to distract from the infinitely greater ruination brought about by the party itself.

During the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, Red Guards confiscated 613,600 antiques and jade pieces from their Beijing owners in just one month, according to the book Mao’s Last Revolution (2008), few of which were ever seen again. More than 70 per cent of 6,843 officially designated places of cultural or historical interest in the city were destroyed, and what remained or had been rebuilt of the Summer Palace sustained further damage.

According to SACH itself, destruction in recent times has continued apace. Of about 225,000 historic sites in China on an incomplete list compiled in 1982, 30,995 had disappeared by 2009.

That foreign destruction, looting and purchase of China’s cultural heritage is statistically insignificant compared with the towering catastrophe the Chinese have achieved for themselves does not provide any excuse for it.

The Greeks, the Egyptians and the people of Benin in West Africa are among others pressing more honestly for the return of “stolen” antiquities, and engaging in debate. It’s long past time certain museums also stood up for their own reputations and against Chinese propaganda, and demanded that accurate and complete accounts be given of both historical events and existing collections.