Robots already perform many traditionally human tasks, from vacuuming to surgery—and they could soon help care for the sick and elderly. But until they can convincingly discern and mimic emotions, their caretaker value will be severely limited. In an effort to create “friendlier” machines, researchers are developing robotic helpers that can better read and react to social signals.

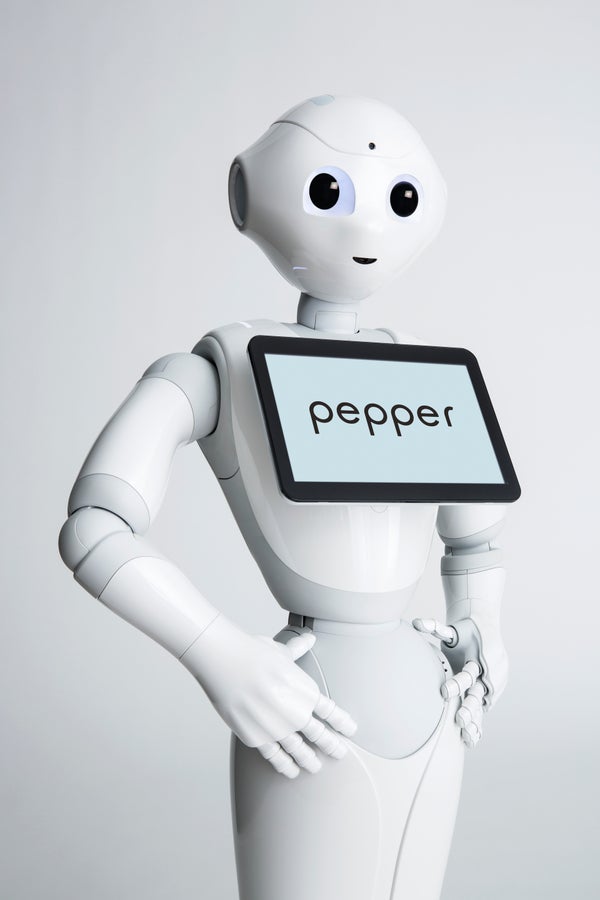

In late 2016 IBM and Rice University unveiled the Multi-Purpose Eldercare Robot Assistant (MERA), a customized version of the Pepper robot developed by SoftBank Robotics in Japan. Pepper, an ivory-colored android about the height of a seven-year-old, can detect and respond to human emotions via vocal cues and facial expressions. It has already been deployed as a friendly assistant in Japanese stores and homes. MERA, specifically designed as an at-home companion for the elderly, records and analyzes videos of a person's face and calculates vital signs such as heart and breathing rates.

MERA's speech technology, originally developed for IBM's Watson (the artificial-intelligence system that won Jeopardy!), allows it to converse with a patient and answer health questions. “It has everything bundled into one adorable self,” says Susann Keohane, founder of IBM's Aging-in-Place Research Lab.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Roboticist Maja Matarić and her colleagues at the University of Southern California are taking a different but complementary approach to developing social machines. They are designing robots that tap into human social dynamics to help seniors help themselves. “What we found is people really need help with motivation” to do necessary tasks, she says. “So we created the field of socially assistive robotics: machines that help people through social, not physical, interaction.” For elderly individuals, such assistance comes in various guises—from coaching them in physical therapy to aiding them in socializing with friends and family.

Matarić and her team recently tested Spritebot, a one-foot-tall green owl robot that assists seniors in playing games with their children or grandchildren. The researchers found that people talked to one another more and played games for longer when Spritebot was participating in, and moderating, their interactions.

In an upcoming study, Matarić and her colleagues will pair elderly people with robot companions that encourage them to form healthy habits, such as walking more. She hopes that monitoring how people interact with companion robots over time will inform her team about both habit formation and the dynamics of the human-robot bond.

The need for socially assistive robots may arise from a shortage of human companions for the elderly, but Matarić points out that robots could also offer some benefits over their flesh-and-blood counterparts. “Machines are infinitely patient,” she explains. “They have [fewer] biases to begin with, and they have no expectations.”