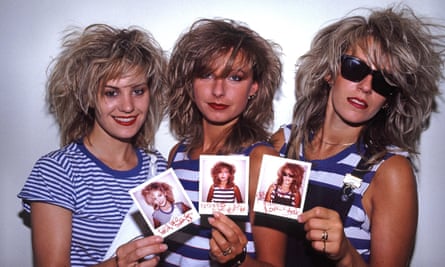

The last time all three founding members of Bananarama were properly together as a band was in 1988 at the Brit awards. They were performing their hit single Love in the First Degree, dressed in black cocktail dresses, flanked by a mini army of topless male dancers, much to the blustering horror of the host, Noel Edmonds. Shortly after that night, Siobhan Fahey walked out on her bandmates Sara Dallin and Keren Woodward, calling time on almost 10 years of pop history. It was a particularly acrimonious split. Dallin and Woodward kept the group going, even replacing Fahey for a couple of years with a different singer, but they were so mad at their former friend, who was mad at them in return, that it has taken almost three decades to rebuild their relationship.

Today, in an out-of-the-way pub in north London – chosen to minimise the chance that fans will see them while their reunion is still a secret – they are Bananarama again. Appropriately, Dallin and Woodward arrive 10 minutes ahead of time, while Fahey, ever the rebel, is 10 minutes late (she flew in from Los Angeles, where she lives, just a couple of hours before we meet). “Shivers!” shouts Woodward, as Fahey strides into the room. “Oh, you poor love.” The three of them hug. “How are you, darling?” asks Dallin. “I might be a little slow,” smiles Fahey, that familiar voice hovering a couple of octaves lower than her friends’.

For a time, seeing the three of them in the same room was about as likely as Morrissey and Johnny Marr reforming the Smiths. But here they are, the biggest girl group of the 80s, the blueprint for the Spice Girls, the punks who became pop stars, about to announce a substantial UK tour. “It was two in the morning, and lots of wine had been drunk, and we were all really emotional,” says Fahey, remembering the barbecue at her then home in Bethnal Green, east London, a couple of years ago, where the seeds were sown. Although they have appeared together twice since the 80s – on Eurotrash in the 90s, and at the 20th birthday party of London clubnight G-A-Y in 2002 – they had always said a full reunion would never happen. There was too much bad blood. They had to become mates again first. At Fahey’s house, it finally happened.

“The feeling of love and friendship had been restored. That night, we really felt it,” she explains. A few months later, Woodward picked up the phone and told Fahey she should come on tour with them. They had never actually done a tour, the three of them, together. “Keren said: ‘You’ve got to,’” Fahey remembers. “‘You don’t know how much we’re loved. You don’t experience that.’”

Did she really not know? “Well, obviously I have some sense of it, because wherever I go, I’m Siobhan from Bananarama. People wet their knickers when they find that out.” Recently, she says, she met the rapper Rick Ross. She beams across the table. “I forgot to tell you! He literally bowed. He said, ‘Oh my God, you guys were so cool. I really want to do a dancehall remix of Cruel Summer.’” They swap stories of unlikely Bananarama fans: the bassist from the Cure, who had all their B-sides. The Cult. Judas Priest. The Prodigy. The Deftones. They did, after all, come from London’s punk scene. “I’m not sure that attitude’s altogether left us, really,” says Woodward.

Bananarama started in London, in 1979. Dallin and Woodward had been best friends since they were four and their closeness, even now in their mid-50s, is palpable – they still sometimes go on holiday together, and say their kids are like siblings. Dallin and Fahey, meanwhile, met while studying fashion journalism, and soon the three of them were a unit. “Our thing was that we loved clubs and we loved music. We were ‘on the scene’, which sounds a bit 60s,” laughs Dallin. They knew musicians, because they went to the clubs they all went to. When they found themselves without anywhere to live, they moved into Sex Pistol Paul Cook’s rehearsal room, full of instruments, and just thought: “We’ll have a go at that.”

“We were breaking the rules of being in a band,” says Fahey. “We all just wanted to be vocalists, so we said: ‘Let’s just be vocalists.’ And that was very against the grain.” Woodward says that while other girl groups had been put together and dressed nicely, Bananarama were “shambolic, to say the least”. That sense of chaos was a big part of their early charm. Fahey says their only ambition was to get on stage and perform; everything else just sort of happened. “We were straight off the street.”

John Peel picked up on their first single, Aie A Mwana, sung in Swahili, more post-punk than camp pop, which had come out on a mate’s label. Terry Hall from the Specials heard it on the radio, and asked them to sing on Fun Boy Three’s single Ain’t What You Do. “We were like: ‘He thinks we’re proper singers,” says Dallin. It took them days to record their parts, because, says Fahey, they just couldn’t get it together in the studio. “I read an interview with Terry where he said: ‘They were impossible.’ We’d be counted in, and then just fall about laughing.”

Ain’t What You Do went Top 5 in 1982, as did its follow up Really Saying Something, this time with the Fun Boy Three returning the favour as backing singers. “It happened so easily, we just assumed that was what happened when you made a record,” Fahey smiles. And it happened so quickly that even though they were Top of the Pops regulars, they were broke, and still had to sign on at the jobcentre. They went in disguise, so they wouldn’t be recognised. They moved in to a council flat in Camden and cobbled together furniture that they found on the street. It didn’t have a kitchen. Woodward’s boyfriend at the time had to build her a bed: “It had five legs, because he accidentally chopped the wrong bit in half.” The three of them are laughing at the state of it. “I just think you don’t care when you’re young,” says Dallin. “You don’t think, what’s my plan? Where are we going?”

Yet, almost simultaneously, they had started to live the high life. In 1983, Cruel Summer went Top 10 in the US. They were suddenly being flown around the world and put up in fancy hotels, which certainly helped them when it came to kitting out their flat. “Off would come the bedsheets, and the towels,” laughs Fahey. “Only high-quality soft towels,” Dallin protests. They still made their own clothes: Fahey remembers bringing pieces of fabric with her on their first trip to Los Angeles and hand-stitching an entire dress together on the plane.

They dressed as if they had run up outfits on their grandmothers’ sewing machines, because they had. They danced like amateurs on a night out, because they were. “We made the routines up ourselves, to start with,” says Dallin. “Do you remember that big choreographer who came up to us and said: ‘You’re dancing on the wrong beat. Who did that for you?’” says Woodward, gleefully. “We did it all ourselves!” Fahey says their moves were rudimentary on purpose. “It was very ironic. We were a girl group, so it was kind of a piss-take of being in a girl group, in our own, shonky way.”

They were banned from a couple of TV shows, once for falling into the set and knocking it over during a live broadcast, and once for “something to do with Keith Chegwin and a baby,” chuckles Woodward. They talk about that time as if it were an endless school trip. People thought they were either surly or bolshy, or a combination of the two. People have told them, in recent years, that they found them terrifying. “Because we moved as one! We probably looked like we were sneering, when, actually, we were really shy,” says Woodward. “There might have been a bit of sneering going on,” Fahey chips in, naughtily. “The thing I’m proudest of,” she continues, “is that we made quirky pop. The lyrics were much darker than you’d imagine. Robert De Niro’s Waiting is about date rape.” “You’ll listen to it with new ears now,” Woodward smiles. “I wanted it to be like Pull Up to the Bumper,” adds Dallin, dryly. “It didn’t quite work out like that, did it?”

By 1986, they were three albums in. The whole operation had become bigger, less shonky, and more glitzy. Woodward is reluctant to say they got slick – “I can guarantee we never will be” – but undoubtedly some of their early shabbiness was polished up. They moved away from their long-term producers Jolley and Swain to a then-emerging production trio, Stock Aitken Waterman (SAW), who had produced Dead or Alive’s You Spin Me Round. The women wanted a similar sound for Venus, a song they had worked up a version of during their early days. “They were saying, it can’t be done,” remembers Fahey, who still looks unimpressed. “I was like, yes it can! Get those cowbells on there!”

SAW’s relationship with the band was rarely plain sailing. Pete Waterman has given a number of interviews in which he claims Bananarama were a nightmare. “They had so many opinions,” he told one TV documentary, wearily, a few years ago. “Yes, he has some very tall tales,” says Woodward, practically rolling her eyes. She says it was inconvenient for SAW that the band weren’t the types to be treated as passive cogs in a hit machine. “Peter was an ideas man, but he was never in the studio anyway,” Woodward shrugs. “That’s because I said I can’t be in the studio with him,” Fahey announces, which is news to her bandmates, although they don’t look surprised.

Although Bananarama had enjoyed “credibility” in the early days, the press soon turned on them. It took its toll on Fahey, in particular, who seems more fragile than the others, more prone to remembering when people wronged them. “One review said they should hand out a free plastic glove with every single, and turn off the life support. I was so angry and hurt. Hand out a wanking glove with every single? Fuck. Off. How fucking dare you? We were young girls at the time, being talked about like that.”

All three women agree that with hindsight, they were pretty good role models, actually. They had done it their way. And for nine years, the public agreed. Bananarama still hold the record for the most singles to chart by a girl group ever. Venus brought them their first US No 1. They were riding high on Love in the First Degree. They were thinking about a world tour. Then Fahey walked out.

“It was a combination of the fact that, musically, we’d gone absolutely full-on pop, at a time when I was feeling lost and dark and depressed in my life. I was obsessed with the Smiths, and I just wanted something that would …” Fahey pauses. Even after three decades, it doesn’t seem to be a comfortable topic. “It had been a real pressure cooker, the three of us being together 24/7, for years. It couldn’t continue.”

Woodward was in a different place entirely. “I absolutely loved and embraced that album [Wow, the band’s fourth],” she says, almost defiantly. “For the first time, I felt, this is what I’m supposed to be doing. Performing pop songs and letting go, just embracing it all. I was thinking: ‘I’m having such a laugh doing this.’”

It took them 10 years to talk to each other again. It was, as Fahey puts it, “a painful divorce. There were sore feelings on both sides. I felt really isolated within the band for a year before I left. And they felt betrayed that I left.” She looks across the table. “I don’t know, I might be putting words in your …” Dallin and Woodward say no, she’s right, simultaneously. “Very much so,” says Woodward. “From my point of view, I just thought: ‘Oh fine, she’s married Dave Stewart and now she’s fucked off and left us in the lurch.’” Fahey takes it on the chin: “It was every bit as intense as a marriage, but without the sex. So we stayed together longer than most marriages these days.”

Fahey went off to indulge her dark side with Shakespears Sister, who had a huge hit with the goth-pop Stay. But there was no question of Bananarama ending. Dallin and Woodward set off on their first world tour, with a new third member, Jacquie O’Sullivan, who was only ever really seen as the new girl, and lasted just a couple of years. “It’s so frustrating, because I left the year before they got their first tour together,” says Fahey. “The whole reason we’d formed a band was to get on stage, and I’d been denied it.” There’s a prickle of tension, just for a second, that Woodward cheerfully dissipates. “Well, not any more,” she trills.

Dallin and Woodward sound like they have genuinely had a blast as Bananarama over the years. Even now, they talk about how ridiculous it is that they can still do it, how lucky they are to travel to places such as Japan and Australia, and stay in nice hotels – where they no longer pinch the sheets – just to perform a few songs, for people who clearly love them. “It isn’t the real world, is it? That’s what’s so great about it,” Woodward smiles. “It’s fantastic. I just want to be in that world the whole time, thank you very much,” says Fahey.

If November’s UK tour goes well, they would like to hit the road in the US, so Fahey can play in LA, and her friends can see it. What about an album? “We’re looking at doing a single, but I’m not sure I was supposed to say that,” Dallin reveals. Fahey says they’re just going to “experiment creatively” in the studio, and see what comes out of it. What about getting Waterman involved? “We’re going straight in to record with him next week,” Woodward fibs. Dallin protests that she likes Peter, actually, and says she doesn’t want to slag him off. “I mean, I’m fond of the old fool,” drawls Fahey. “He’s a massive fan of music,” says Dallin, ever the diplomat. “Music, trains, and bull semen, he used to talk about that a lot,” says Woodward, and then the three of them collapse into giggles.

Tickets for Bananarama’s UK tour go on sale on Wednesday (aegpresents.co.uk)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion