By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Martin Scorsese on Fighting For Film Preservation and Not Believing in ‘Old Movies’

READ MORE: Christopher Nolan Joins Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation

Martin Scorsese is not only one of our most important living directors, but he also may be the world’s biggest cinephile. With a famously encyclopedic knowledge of film and an unparalleled love for cinema, the director has committed himself to making movies, as well as to preserving some of the best films of the 20th century. Through the Film Foundation, he has helped to restore over 700 films, which are now available to the public once again through festivals, museums and educational institutions.

Taking the stage at the New York Film Festival following a revival screening of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1943 classic, “Heaven Can Wait,” Scorsese discussed the origins of the Film Foundation and the importance of film preservation. Check out the highlights from his discussion below.

Thank Marilyn Monroe for Scorsese’s interest in film preservation

When asked when he began to take an interest in film preservation, Scorsese was able to point to a specific incident as a young director working in Hollywood. He recounts a double feature of “Niagara” and “The Seven Year Itch,” two Marilyn Monroe star vehicles made only two years apart. The two films were studio prints from Twentieth Century Fox’s own collection. “Niagara,” printed on technicolor nitrate, was in gorgeous condition, while the monopack celluloid of “The Seven Year Itch” was already badly faded.

The discoloration was so bad the projectionists tried to put gel filters over the lens as a makeshift color correction. “You’re missing the narrative. You’re missing the performance. Something’s wrong with the image.” he said, remembering the viewing experience. “And then you put the gels on, and the image starts to get off. And then people started to stamp their feet, and people started to get mad. Then we were like, ‘Let’s get out of here.'”

Scorsese left the theater disturbed by the poor quality of the print, which was barely more than a decade old: “We were so disappointed. Our eyes were so treated to this extraordinary Technicolor of ‘Niagara’ which preceded it that this was like falling off a cliff watching it this way, it was a shock.” At this moment, Scorsese began campaigning for better preservation of studio film prints and for a more stable color film stock, but it would ultimately take nothing less than a reimagining of the value of film as an art form for the studios to take a serious interest in film conservation.

The importance of Film Foundation is to be a middle man

“The whole key of the Film Foundation itself was to unite the archives with the studios, because it turns out the studios weren’t just in production and distribution of the film, they were in production, distribution and conservation. In a way this art belongs to everyone, and you’re the custodians. You have a great responsibility,” Scorsese said.

The “experience” of film

“I was talking about showing certain classic films at times off a Bluray projecting on the big screen for young people who are 13 or 14 years old, the impact of the film — if it has any — is still the same,” Scorsese said. “But it’s not a film experience, it’s a different kind of experience, I think akin to the difference between nitrate film and the celluloid we’ve been familiar with for the last fifty years or so.”

Scorsese kept studios updated on film history

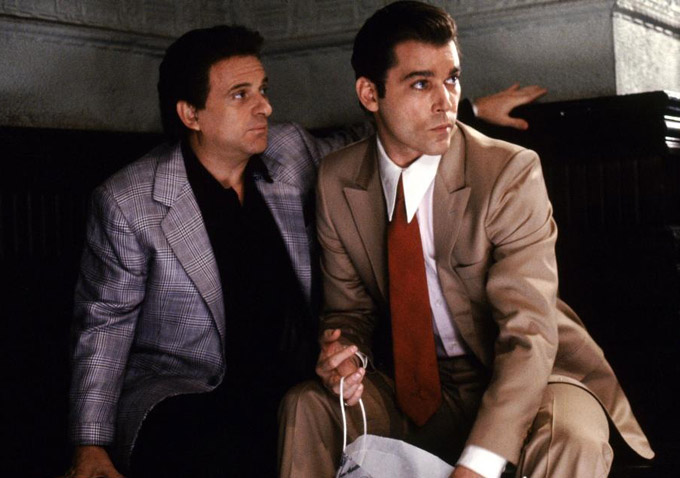

“While I was editing ‘Goodfellas,’ I went through these books that they called ‘The MGM Story’ and ‘The Warner Bros. Story,’ and they had every film the studios ever made, and I started trying to put them in order not of importance but a kind of necessity, whether it’s a film I liked that I thought was overlooked, or it’s a fim — let’s stay it’s Warner Bros.’ first two-strip Technicolor film, and I’ll say, ‘That’s important.’ So I tried to put it into A, B and C categories, and we put them into books,” Scorsese said. “And then I’d try to bring these books to the heads of the studios and they’d let me in because I’d done ‘Goodfellas.’ I think it was one of those things, like, ‘Yeah, it’s a good film, people like it, but he has this thing… just let him do his thing.'”

The nature of film as art and commerce

“There was a question of its value as a work of art. How can it be a work of art if it’s a commercial thing? It means a lot to people, it’s inspired people who are artists, novelists, poets, painters. Not people who are simply enjoying making a narrative from film. If you think art is important at all, whether it’s commercial or non commercial, it seems to me it’s art — with all that effort and all that love you put into something, it might mean something to people,” Scorsese said.

“I put together a program [of] trailers in color, one of them being ‘Invaders from Mars’, and they were all laughing in the audience — this is one of those films that at a certain age, certain people saw and it’s your cinema now. This is where it came from,” Scorsese said. “And so if you’re one of those people who says, ‘Invaders from Mars,’ silly title, who wants to see that? Let it rot’ — well, it changed the industry.”

Scorsese won’t let the art fade away

“I thought about this idea of fading, and if that’s what you think about our culture then there’s nothing in the culture. It’s a culture that you use up and you throw away. You don’t care about it. Well everyone goes walking around thinking that the film that changed their life or the book that changed their life, thinking it’s going to be there all the time, and keep some continuity with the younger generations,” Scorsese said.

“I showed a clip of a rocket going up to the moon — NASA footage — and it was in glorious magenta. We made it to the moon, but the film is gone. What kind of thinking is this?,” Scorsese said. “And then [home] video started, and then they started to realize there’s no such thing as an old film, just a film you’ve never seen. That’s all.”

READ MORE: Exclusive: Martin Scorsese on the Pros and Cons of Digital Filmmaking

By providing your information, you agree to our Terms of Use and our Privacy Policy. We use vendors that may also process your information to help provide our services. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA Enterprise and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.