The other day, I had to hire an electrician. Now, I don’t know any electricians, so this was a shot in the dark, and as I went down the list of electricians named Tom, Dick and Harry, I suddenly came across Kelly and her colleague Sarah. Hmm, I thought, female electricians, that’s unusual. So I hired Kelly and Sarah, and I felt very proud of myself. I had struck a blow for gender equality, after all.

And it did not go unnoticed. A neighbour remarked approvingly on the fact that a woman had arrived at my door with a box of tools. Others referred in conversation to my electrician as “he” and I was able pointedly to correct them, “she” not “he”.

Then I realised that actually, if hiring a female electrician was striking a blow for gender equality, then we are in pretty bad shape. On her website, Kelly says she became an electrician because she likes problem solving. And since when was problem solving a preserve of men? I began to feel the same way I feel when I see news stories excitedly reporting that a toy manufacturer has decided that not all girls’ toys should be painted pink. Really? All these years, and that’s where we’re at?

There are so many things that should be unremarkable – like female electricians, and like blue toys for girls. Better still, that the word “electrician” should conjure up a Kelly as easily as a Kevin in the mind’s eye, or that when someone puts a toy into our hands, we have no clue as to whether it’s marketed for boys or girls because… Hallelujah… it’s for both.

It’s so easy for all of us to slip into easy assumptions about gender, women included. Writers included, too. I was once told by a publisher that I should aim to write about “women in danger”, because readers lapped them up. He was right about that – there is a vast oeuvre of crime fiction about young women as victims, some of it more palatable, some of it verging on torture porn.

Well, it’s one thing to write about women in danger like men are sometimes in danger, that is, they have got themselves into a threatening situation. It’s another to write about women who are in danger because it’s a state of being, as though the entire sex are weak, or frail, or vulnerable.

As a writer, I think long and hard about the girls and women I portray. I don’t want them to be superheroes, because that’s pretty depressing to real girls and young women. I want them to be realistic, and I want them to reflect how women really are, which may be tough, brave, smart, proactive, or weak, passive, manipulative, impressionable. I try to write about women at work and in in a family context – we all have multiple roles, as boys and men do too.

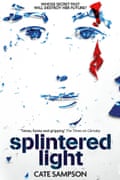

At the heart of my new book for teenagers, Splintered Light, is a young woman called Leah, who has faced danger and tragedy in her short life. It is true that she is a young woman in danger. In one way, she’s a victim, and she bears the scar on her face. And yet she refuses to let that define her, taking control of her own life, trying to unravel the mystery that surrounds the murder of her mother when she was four years old.

Leah’s a strong female character, but when I write that I don’t mean to say that the word “female” should suggest otherwise. She’s a strong female character in the way that there are strong male characters and weak male characters, and in the way that there are weak female characters. Leah’s not on her own either in literature or in real life, and to pretend she’s unique or unusual would be unfair to her gender, as though suggesting that by and large we’re a wimpy lot.

There are plenty of strong young women, both in literature, from Jo in Little Women, to Katniss in the Hunger Games, and in real life. Young women like Malala Yousafzai, the real-life 17-year old Pakistani who stood up for education for girls and was shot by the Taliban. Somehow, Emma Watson has managed to be a strong female character both in the fictional world and the real world, playing Hermione in Harry Potter, and standing up to internet trolls after making an impassioned speech at the UN for gender equality.

The peculiar power of fiction means that readers absorb messages from a novel in the same way they may absorb the messages of real life. Novels are primarily entertainment not message boards, that’s not in question, but to pretend that we don’t absorb signals from them is to stick our heads in the sand.

I made Leah a kickboxer in Splintered Light, not because I wanted her to be some kind of action hero, but because of what it said about her. In my mind, the fact that she devoted her free time to kickboxing told me that she wanted to take control of her life, that she didn’t want to be afraid of anyone. It also said to me that she was at ease with her body, and that she faced men on equal terms. I want to think that she might become an electrician, or a neuro-surgeon, or a chef or a comedian, and that it will be her personality and her drive that will decide what path she takes, and not her gender.

- Cate Sampson’s Splintered Light is available from the Guardian bookshop.

Find out more about the HeforShe campaign: a solidarity movement for gender equality.