The Skills Gap: America's Young Workers Are Lagging Behind

New findings suggest that U.S. millennials are far less competent than their peers in Europe and Asia.

Young American workers today are more educated than ever before, but the nation’s largest generation is losing its edge against the least and most educated of other countries, according to a provocative new report.

The report’s authors warn these findings portend a growing gap between rich and poor American workers and that the lackluster results threaten U.S. competitiveness in an increasingly globalized market.

The report, produced by testing giant ETS, analyzes data collected by the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). The assessment measures the literacy and arithmetic skills of workers ages 16 through 65 in the U.S. and in other wealthy countries. While the results of the PIAAC have been published before, the new ETS study offers new insight in that it compared U.S. millennials—those between the ages of 16 and 34—with their international colleagues in roughly two dozen countries. The analysis found that more than half of U.S. millennials lack proficiency when it comes to applying reading and math skills at the workplace.

"You’ve seen tons of school-reform efforts in the last 20 years that don’t seem to be able to make a dent. Well, maybe we need to reframe the problem in a larger way," Madeline Goodman, a co-author of the ETS report, said in a phone interview. "It’s a question of putting the problem of skills in a larger context of inequality and opportunity in America today."

Meanwhile, Tom Loveless, an education scholar with The Brookings Institution, said that while the PIAAC results aren’t surprising, the maker of the assessment "is unabashed about its ambitions in this regard ... [it] believes it’s measuring skills that matter in the 21st century. Put me in the ‘I’m skeptical of that claim’ group." While keeping those caveats in mind, the ETS report is worth analyzing and paints a dispiriting picture of U.S. competitiveness. Among the findings:

- Even though U.S. workers complete high school and college at rates similar to those in high-performing countries, U.S. PIACC scores for workers ages 25 through 34 are on par with those in the least educated of participating countries and territories.

- On literacy, America's millennials posted an average score of 274 on 500-point scale while the average among participating countries is 282.

- On numeracy, U.S. millennials are in a statistical dead heat with Spain and Italy for last place, showing an average score of 255 while the average for participating countries is 275 on a 500-point scale.

- One half of U.S. millennials scored below the threshold that indicates proficiency in literacy. By comparison, high-flying nations like Finland and Japan had between 19 percent and 23 percent of their millennials miss the threshold for proficiency in literacy.

- Those same countries had roughly a third of millennials miss the proficiency cut-off score in numeracy, while roughly four in ten millennials in countries like the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Estonia performed below proficiency. Two-thirds of U.S. millennials missed the cut-off mark in numeracy.

- The U.S. had the largest gap in numeracy scores between its millennials in the bottom- and top-10 percent of all performers, and both U.S. groups posted some of the lowest scores compared to other participating countries.

- Perhaps more unsettling, the report indicates that the literacy and numeracy skills of U.S. workers today have largely declined compared to those in the labor force two decades ago.

"As a country, we need to address the question of whether we can afford … to write off nearly half of our younger-adult population as not having the skills needed to effectively engage as full and active participants in their own future and that of our nation," write the authors of the ETS report.

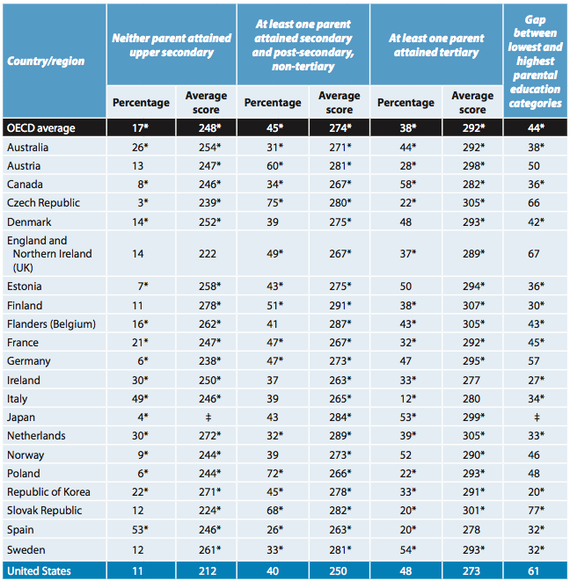

The ETS report also indicates that parental education levels correlate more strongly with U.S. millennial numeracy proficiency than in other countries, suggesting America’s middling scores would be much lower without the high college-completion rates of the previous generation.

Goodman and co-author Anita Sands also ruled out the effect non-native workers have on U.S. millennials' scores, pointing to data that showed American workers born here and abroad performed near the bottom compared to young workers with similar profiles in other participating countries.

PIAAC is produced by the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development, the same organization behind Program for International Student Assessment; since 2000, that academic assessment has found U.S. 15 year-olds to be below average in math and science compared with their peers in other countries. And the International Student Assessment is one of several worldwide tests that have found U.S. students trailing their peers elsewhere. In 1964, the U.S. ranked 11 out of 12 on the first international math assessment—and that was in the middle of a decades-long period of prodigious economic growth.

A January report by the liberal advocacy group Washington Center for Equitable Growth calculated that if the U.S. were to invest in resources to raise the performance of its 15-year-olds on the International Student Assessment—bringing them on par with the average score of test-takers worldwide—the result would jumpstart the economy. The center's researchers concluded that the investment would yield an increase of $900 billion in the country’s local, state, and federal tax revenues over the next 35 years. Those gains far outweigh the resources necessary to improve U.S. student scores, the report’s authors wrote.

Goodman cited the kinds of policy decisions that have shaped the U.S. in the last four decades, largely in response to "globalizing changes in the economy and technology ... But all of those global forces have affected European countries, as well, and yet they made different kinds of policy choices and have different results."

Loveless of The Brookings Institution says that, empirically speaking, the PIAAC results don’t match up with existing data about the U.S. economy’s performance. But a bigger qualm Loveless has is the assumptions that the adult-competencies assessment makes about the skills workers will need going forward. "Let’s say I was alive in 1915 and I gave a test that predicted the job skills and future economic productivity of nations," he said. "I just don’t see how anyone in 1915 could have foreseen the skills that would have been important for the rest of the 20th century, and I doubt that anyone’s doing that now for the 21st century."

No test maker, Loveless said, "has come up with an assessment that’s a crystal ball like that."

But the report’s authors said their findings are consistent with other data sets that capture where the U.S. stands academically on both a national and global scale, particularly the International Student Assessment and the Nation’s Report Card, the federal exam that measures the academic proficiency of students in certain grade levels. "If our data were showing something that’s not in line with other kinds of large-scale assessments, it might raise questions," Goodman said. "But that’s not the case."

This post appears courtesy of The Educated Reporter.