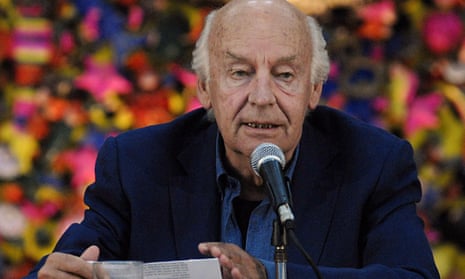

Eduardo Galeano, who has died aged 74, was one of the great writers of Latin America; his unusual and idiosyncratic works served to illuminate the history and politics of the entire continent. Born in neglected Uruguay, he was a significant part of the “boom” generation of the 1960s, inspired by the Cuban revolution, that put Latin American fiction on the global map. Although Galeano wrote novels, he was a radical journalist by trade, a poet and an artist, and a brilliant editor. He was famous for pioneering a form of political essay built on his encyclopedic knowledge of Latin America’s past, and his writings bear some comparison with the similarly innovative works of Ryszard Kapuściński and Sven Lindqvist.

One of Galeano’s early works, Open Veins of Latin America (1971), received an unexpected publicity boost in 2009 when Hugo Chávez, president of Venezuela, thrust a copy into the hands of the US president, Barack Obama, at a summit meeting in Trinidad. Obama read it, which was not altogether surprising, as an English version, subtitled Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, had been available on US campuses since 1973.

Galeano was born in Montevideo to a solidly middle-class and Catholic family. His father, Eduardo Hughes, was a civil servant of Italian and Welsh descent. From his mother, Licia Galeano, he acquired his pen name. His newspaper career began at the age of 14 when he drew cartoons for El Sol, the weekly of the Uruguayan Socialist party. Sometimes he illustrated the columns of Raúl Sendic, a trade union leader who subsequently became the leader of the Tupamaros guerrilla group. Galeano signed his cartoons with the name Gius, designed as a Spanish form of his father’s name. Later, he migrated as a desk editor to Marcha, the influential political and cultural weekly, edited by Carlos Quijano. Then, caught up in the prevailing enthusiasm for the Cuban revolution, he moved briefly to be editor of the leftwing daily La Epoca.

He travelled to China and wrote a book about his adventures, and he also visited Guatemala and wrote about the guerrillas, in Guatemala, País Ocupado (1967). Perhaps his most famous moment as an editor came when he was first exiled to Buenos Aires in 1973 and put in charge of the weekly magazine Crisis. Born at a moment of exhilarating political excitement, with left battling right in an atmosphere of accelerating disaster, Crisis reflected the dramas of the moment, its pages filled with some of the most distinguished writers of the time, from all over Latin America.

Eventually, after the death of President Juan Perón in 1974 and the coup d’état of General Jorge Rafaél Videla in 1976, Crisis was closed by the military, and Galeano again found himself in exile. He re-established himself in Spain, writing an autobiographical account of those years, Days and Nights of Love and War (1978). This is a frightening story, familiar to all those who lived through the military dictatorships that seized control of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Brazil and Uruguay.

When Galeano returned to Uruguay in 1985, after the fall of the dictatorship, he decided with friends to re-establish Marcha. But since the old editor, Quijano, had died in exile in Mexico, they decided to give it a new name, Brecha.

By now, Galeano had an established voice as a writer, and he soon settled down to write a series of books that embellished the formula that had proved so successful with Open Veins, combining contemporary observations with historical anecdote. “I’m a writer obsessed with remembering,’’ he once said, “with remembering the past of America above all, and above all that of Latin America, intimate land condemned to forgetfulness.”

This first new beginning, entitled Memory of Fire, is a three-volume history of the Americas (and sometimes of London and Madrid), told year by year in an enthralling series of anecdotes. The first volume, published in Madrid in 1982 as Los Nacimientos (Genesis), when he was still in Spain, covers pre-Columbian times and subsequent history until 1700. The second volume, Faces and Masks (1984), deals with the 18th and 19th centuries, and the third volume, Century of the Wind (1986), brings the story up to the present day. It was his tour de force. Among his last and most well-regarded books was a wonderful account of Latin American football, Football in Sun and Shadow (1999).

Galeano was a charismatic figure, popular on political platforms and in print, with a tireless if sometimes melancholy enthusiasm for socialism and national liberation. As a journalist, he interviewed most of the famous figures of the continent, including Fidel Castro, Perón when exiled in Spain, Chávez and Salvador Allende, who was a close friend.

Galeano is survived by his third wife, Helena Villagra, whom he married in 1976; a daughter, Veronica, from his first marriage, to Silvia Brando; and Florencio and Claudio, the children of his second marriage, to Graciela Berro.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion