In 1985, citing concerns regarding “difficulty determining what has been publicly disclosed,” the CIA had a truly great idea that would serve both the Agency and the public’s interest in government transparency - a “proposal to establish a focal point to record CIA information released to the public.” The resulting Officially Released Information System, or ORIS, would take years to finally implement, and thanks to a recent FOIA - and the CIA’s agreement to release and waive all fees - it might finally become the transparency tool it has the potential to be.

The problem of knowing what had already been acknowledged wasn’t a new problem to the Agency, either. The issue extended back to the 1970s for them, and had been brought up again in 1983. Previous attempts had all failed or resulted in incomplete division-specific systems. CIA needed an Agency-wide solution, and it was finally beginning to be technologically feasible.

The extremely limited system in place only applied to individual departments and directorates, with at least one knowing what documents were released - but not what those documents said or were about. Another system captured released texts on film, but was designed for other purposes as well as being “far from comprehensive” and “not designed for Agency-wide use.”

In response to these problems, the OIS wanted to create a new system to capture and display the text of released documents, including any images or handwritten notes - the Officially Released Information System, or ORIS. The OIS was concerned, however, that it would take years to implement such a system and that needed information might be lost in the meantime.

While OIS had access to some of the information they needed, there were other types of releases they didn’t have “routine access to.” As a result, additional procedures would need to be devised with Agency-wide participation. To fulfill this need, the proposal called for a task force to be headed by the Deputy Director of Information Services.

According to an excerpt from the concept paper, the system was to be rather inclusive. It was meant to include any previously classified information, including information released by another government agency with CIA identified as the source. It was also meant to include “material declassified and released outside the Agency” which would seem to include materials reviewed and declassified by Congress or as a result of the an act of Congress such as the JFK Records Act. Curiously, the Agency has claimed that even describing the final type of unclassified and officially released to be included in the database is exempted from release by statute.

A memo sent later that year indicated that the project was on track. The Deputy Director of the Office of Legislative Liaison (OLL) drafting the memo urged that the system include “full text of every document” released, which would greatly aid in FOIA research.

According to the Deputy Director, OLL would contribute additional unclassified information that didn’t qualify as previously released. This would include formal view letters, proposed legislation, letters to Members of Congress, and unclassified Congressional testimony. While not previously released, all of this information was unclassified and releasable.

By 1986, the system had been partially implemented was useful enough that Agency personnel from the Classification Review Division were requesting direct read-only access to the system. The first steps were being taken to make the system Agency-wide.

Judging by the notes on the routing sheet, this proposal not only met with no objection but with a proposed expansion - CRD personnel should also make copies for their own office.

According to the ORIS storage requirements, the system was initially projected to contain 400,000 pages.

Alongside this estimate were a number of architecture proposals, many with diagrams.

While the proposed system would be a boon to FOIA requesters and public researchers in many ways, CIA listed the system’s first priority as helping limit the release of additional information. Many FOIA requesters, including my friend and fellow FOIA punk Ryan Shapiro, have felt the sting of an exemption claimed under the “mosaic effect.” As explained by CJ Ciaramella, “among federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies, there is a justification for withholding documents known as the “mosaic effect.” The fear is that, by piecing together enough tiny pieces of information, criminals, terrorists, and foreign counterintelligence can gain a working picture of law enforcement and IC activities.”

The ORIS database would allow employees to analyze not only what information was released, but how a new release would add to the collective sum. The paragraph specifically cites the “mosaic effect,” noting that they are required to protect sources and methods. While the basic notion is undoubtedly legitimate, there are no shortage of FOIA requesters and investigative journalists who can attest to the mosaic effect being abused to prevent the release of information.

The secondary purpose to the system was to enable “damage assessments” of intelligence sources and methods being compromised by official releases. While they don’t cite the “mosaic effect” by name, they do refer to analyze “the aggregate of released information.”

The next several purposes of the system were all boons to the FOIA community.

The system would also be used to fact check the media and determine if alleged CIA documents were real or authentic, though it’s unclear if this would aid in documents which had allegedly been leaked.

The document goes on to list material that would be included in ORIS. This listing chooses not to redact the final piece type of material that would be included - “material prepared for elements of the private sector.” Unfortunately, this is only instance of many where CIA’s redactions in CREST are either contradictory or downright nonsensical, such as describing cafeteria construction as being protected by “sources and methods.”

According to the proposal, while the system would have some classified documents, they would have a limited purpose and access would be restricted.

The system would also give users a way to warn of “inadvertent releases or special circumstances releases.”

According to this proposal, the size of the system was now larger than in the original concept. It now estimated 500,000 to 700,000 pages. A 100 gigabyte hard drive was thought to be more than sufficient. For comparison, the size of CREST comes to over 500 gigabytes.

The document specifies that while the individual releases in the system are all unclassified, “the releases in aggregate will be classified Confidential” per a National Security Classification Guide (NSCG) citation, the identity of which the Agency says is exempt from disclosure. Under another NSCG item, also restricted, the system itself was to be classified Secret.

The document concludes by noting the anticipated schedule for ORIS.

The document’s footnotes are unremarkable, except for a note that ORIS is “is Latin for ‘of the mouth.’ ORIS is intended to capture what the CIA ‘says’ as other systems capture what the CIA collections through its ‘eyes and ears.’”

A memo shows that in 1988, there was strong resistance to creating the system as a massive and complete undertaking because it could “be an embarrassment to the Agency if information, for some reason or another, showed up in the public domain and was not recorded in the central system.”

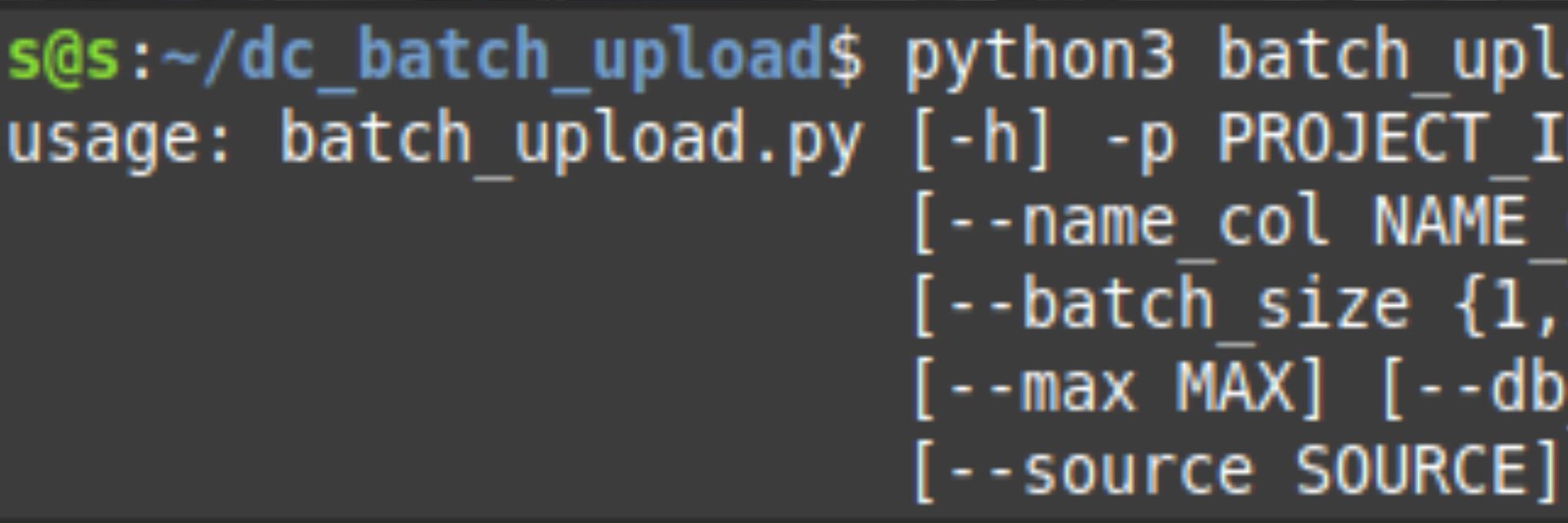

Several months later, a document is authorized which ambiguously describes the scope of ORIS simply as tracking information on “officially released documents.” By early 1991 however, the system was online and SQL-based. The Letter of Acceptance specifies that it tracks information released through the Freedom of Information Act and Executive Order 12356. While it’s not clear if ORIS is as inclusive as it was once described, this does clearly distinguish ORIS from the CREST database.

This leaves a significant question: did/does it include information declassified and released by other government agencies or by Congress, such as through the JFK Records Act or the House Select Committee on Assassinations? There certainly seem to be gaps in the system - or at least in how it’s being used. A FOIA request to CIA regarding their former employee Morton Barrows “Tony” Jackson was met with the unbelievable response that the Agency was unable to locate any acknowledged CIA affiliation. This claim was made despite the fact that not only do declassified CIA documents discuss his employment, but the Agency was pointed to copies of these documents in the initial FOIA request.

By the year 2000, OSIR was considered a “legacy” system and its contents had been merged into the next generation system, Management of Officially Released Information (MORI) which had become operational in 1998. By 2006, MORI was considered aging. It now seems that MORI has been replaced (or at least supplemented) by CIA Automated Declassification Review Environment (CADRE).

FOIA requests have been filed for more information on ORIS and for a copy of the information in the system - which CIA has recently agreed to waive fees for. Future requests will be filed for materials on and from MORI and CADRE. In the meantime, read the 1985 memo embedded below.

Like M Best’s work? Support them on Patreon.

Image via CIA Flickr