You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Faculty members may not be flocking to all-online class formats, but they’re using technology and other pedagogies to make their classrooms more student-centered. Faculty members are divided, however, along racial, ethnic and gender lines about the state of diversity and climate at their institutions. And while non-tenure-track professors seem to be getting some advance notice for courses, they’re still denied basic resources with which to do their jobs.

Those are some of the major findings of a new report from the Higher Education Research Institute at the University of California at Los Angeles. The institute’s Undergraduate Teaching Faculty survey is published every few years, and it's one of the most comprehensive national data sets on the attitudes and working conditions of undergraduate instructors. This year’s report covers 2013-14; the last was published in 2012. That study found that professors were spending less time teaching and suffering stress from a variety of sources – especially at public institutions. But they still wanted to be college professors.

This year’s report focused on different areas. For Kevin Eagan, the report’s lead author and assistant professor in residence and director of the Cooperative Institutional Research Program at UCLA, the survey points to two important but somewhat divergent trends in teaching. While professors aren’t embracing all-online instruction, they are mixing up their teaching in increasingly student-centered ways, and they are frequently using technology to do so.

Student-Centered Teaching

“It’s still less than one in five faculty members reporting teaching exclusively online,” Eagan said in an interview. “I think that the lack of movement among faculty to teaching a course exclusively online is interesting, considering all the conversations about moving online in the past few years, in regard to MOOCs as a way for colleges and universities to increase number of students they’re reaching.”

The data show a small increase in the number of professors who have taught a course exclusively online between surveys. In the 2012 report, 14 percent of faculty members said they’d taught a course online. This year, it was 17 percent. The proportion of professors who have taught online is biggest at public four-year colleges, at 27 percent this year, up from 24 percent in 2012 – still modest gains. Full professors are least likely to report teaching a course all online. Inside Higher Ed's recent survey of faculty attitudes toward technology also suggests widespread skepticism of all-online instruction.

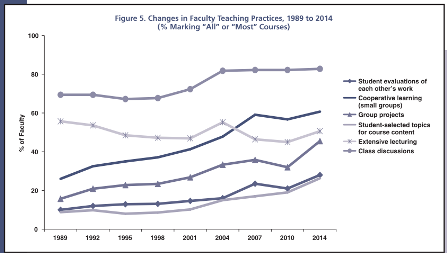

Eagan said the “second story” about instruction is that professors -- while unsure about online education -- still appear to be moving toward “student-centered methods.” It’s a shift observed by the survey spanning the last 25 years.

This year, for example, 83 percent of faculty members reported using class discussions in all or most of their classes, up from 70 percent a quarter-century ago. The number of faculty members using student-to-student evaluation in most of their courses also increased, to 28 percent this year, from 10 percent in 1989-90. More teachers also are using student-selected topics for course content (26 versus 9 percent over the same period).

Professors are using technology, such as YouTube and other videos in the classroom. Some 50 percent said they do it occasionally, and 36 percent of professors do so frequently. About 16 percent of professors frequently ask their students to contribute to online discussion boards, while 34 percent occasionally do.

Professors of business, engineering, fine arts and education were the most likely to say they “frequently" assign work requiring their students to work outside of class with classmates. Those in history or political science, English, biology and the social sciences were the most likely to say they “frequently” require assignments asking students to “weigh the significance and meaning of evidence.”

Eagan said it’s not only colleges and universities putting pressure on professors to make changes in their teaching, but also external agencies such as the National Science Foundation. It has recently awarded large grants for experimentation with such techniques.

The student-centered teaching trend is especially apparent for junior faculty members, Eagan said, which means that it will only increase over time as these professors “move through the academic pipeline.”

Most of the new report was based on responses from 16,112 full-time undergraduate teaching faculty members at 269 four-year colleges and universities. The faculty participation rate was about 35 percent over all.

Tracy Mitrano, former director of IT policy at Cornell University and a blogger for Inside Higher Ed, said the institute’s data on technology and teaching appear “accurate.” She cautioned against assumptions that the findings reflected faculty preference, however, since “individual institutions may not have raised the profile of online learning to the level of strategic planning.” Online learning is very expensive, she added, so institutions may not have the funds to support such initiatives. Insofar as the data do reflect faculty preferences, she said, online teaching requires a pedagogy that some may not have learned or embraced yet. But she said this is something that could change, as higher education is rapidly evolving and becoming more global.

Diversity Concerns

A more sobering section of the report deals with ongoing faculty concerns about diversity and climate among faculty members.

Male faculty members (68 percent) were slightly more likely than female faculty members (60 percent) to agree that their institution has “effective hiring practices and policies that increase faculty diversity,” according to the report. But the differences are more stark along racial and ethnic lines.

Less than half of Latino faculty members (49 percent) and just 43 percent of black faculty members said their institutions are effective at fostering diversity among professors. But 71 percent of Asian and 66 percent of white faculty members said they are.

Faculty members also were divided in their perceptions about campus climate. Over all, about 12 percent of faculty members said there is “a lot” of racial conflict on their campus. But just 10 percent of white professors said so, compared to 19 percent of Latino, 26 percent of Asian, and 27 percent of black faculty members. Those numbers were inverted when professors were asked if their institution was “unprepared to address a diversity-related conflict in class,” with higher proportions of faculty of color agreeing.

“These data suggest an opportunity for institutions to craft professional development workshops to provide faculty with the resources necessary to address diversity-related conflict in class,” the report says.

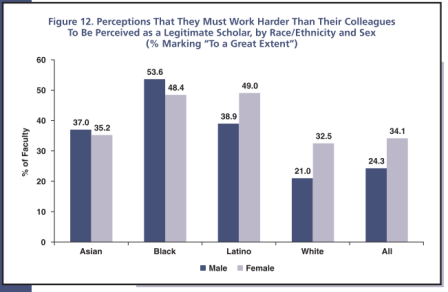

Faculty members also reported being personally affected by climate conditions on their campuses. Overall, 3 in 10 faculty members reported feeling, “to a great extent,” that they must work harder than their colleagues to be perceived as a legitimate scholar. More women (34 percent) than men (24 percent) reported feeling like they have to work harder than their colleagues, with white and Latina women faculty being more likely than their male counterparts to feel that way. But Asian men (37 percent) and black men (54 percent) are slightly more likely than their female counterparts to feel “to a great extent” that they have to work harder to be perceived as legitimate. (Black men were the most likely of all groups to report feeling this way.)

Respondents to an optional module of the survey (8,376 faculty members from 86 institutions) also reported experiences with discrimination in large numbers. About 57 percent of black faculty members said they have been discriminated against or excluded from activities because of their race or ethnicity. Some 40 percent of both Asian and Latino faculty members said the same, compared to just 6 percent of white professors. Women reported higher rates of gender-based discrimination, as well – 38 percent, compared to 12 percent for men.

Similarly high numbers of faculty members said they’ve witnessed an act of discrimination, but relatively few have reported it to campus authorities. Among black men, for example, 74 percent said they’ve witnessed discrimination, but just 38 percent have reported it.

Eagan said he “wished” he’d been surprised by the data on diversity, but wasn’t. He encouraged individual institutions and departments to break down their data to see what’s happening on their campuses, and get to the “root cause” of why “roughly half of black faculty are saying they feel they have to put in more of an effort to gain respect and achieve legitimacy among department colleagues,” and one in three women are saying the same. He pointed to his university’s 2013 Moreno report, which addressed on-campus climate issues, as one example of how such issues have been tackled head-on.

Richard A. Baker, vice president for equal opportunity services at the University of Houston and a regional director for the American Association for Access, Equity and Diversity, said that while the data are “troubling, what is even more troubling is that they persist within institutions that could otherwise provide America with its greatest model of merit, equality, and opportunity." He added: "Intellectually, we are better than this, but this appears to be who we are because, over time, the questions and answers do not appear to change.”

Beyond the obvious, though, Baker said, the data are helpful in “supporting the discussion for systematic transformational change in the way we recruit and retain underrepresented talent into successful careers in higher education.” That’s because “how we treat people and how people feel they are being treated" is a matter of institutional viability and competitiveness, he said.

Catherine Hill, vice president of research for the American Association of University Women, said the gender differences observed in the report are "consistent" with other research suggesting that women have to do more to establish "professional credibility, especially in male-identified fields" such as engineering and computer science.

Resources for Adjuncts

Although the bulk of the institution’s report regards only full-time faculty, this year it includes an unprecedented amount of data regarding part-time adjunct faculty. Eagan said there are still limits to the data, since many institutions don’t have effective ways of reaching all their adjuncts. But he said the data set – an unweighted sample including 2,593 responses from adjuncts at 168 institutions – is still one of the most comprehensive nationally for this ever-growing portion of the faculty.

In better news for adjuncts – and in contrast to a common narrative of adjuncts receiving course assignments at the last minute – many reported getting some time to prepare for classes. About 40 percent of adjuncts at all institution types reported having between one and three months' notice. An additional group of respondents – some 37 percent of adjuncts at public universities and 33 percent at private, four-year colleges – get even more time, according to the data.

Still, about one in six adjuncts about (16 percent) working at private universities or public four-year colleges reported having a maximum of two weeks to prepare for their courses.

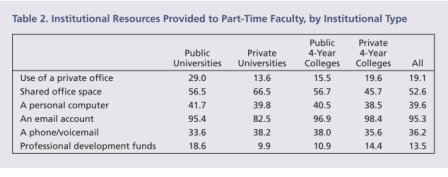

Many adjuncts still lack access to institutional resources and professional development. Across institution types, just 19 percent said they had use of private office space – although 53 percent reported having access to a shared office. Just 40 percent have access to a personal computer, and 36 percent to an official phone or voicemail. Most (95 percent) do have a university email account (although that number could be inflated, given that the survey was shared via email in many cases).

Just 14 percent have access to professional development funds.

Eagan said he was pleased to see that part-time faculty appear to be getting more notice for courses than is often reported, adding that he didn’t know if he could possibly teach a course with just a week to prepare. But he encouraged institutions to invest in resources such as office space.

“Campuses really need to provide ways for those faculty to meet with students; otherwise those conversations are happening in parking lots and hallways,” he said.

Perhaps the most significant finding, Eagan said, was that just one in eight adjuncts have access to professional development funds.

“This represents a huge opportunity for colleges and universities to consider investing,” he said. “It speaks to the areas beyond basic resources that provide the opportunity for faculty to connect with the field and attend workshops to improve their teaching.”

Adrianna Kezar, professor of higher education at the University of Southern California and director of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success, said there was little “news” in the report, but that it included “meaningful questions.”

She said the data on notification time was important, but that the report may have overstated how good it is that 40 percent of professors get one to three months’ course notice, since many others still get little time. She agreed with Eagan’s assessment that professional development for adjuncts would be a prudent place for universities to invest.

Kezar said she wished that the report had focused even more on adjunct faculty, since they now make up the majority of instructors across higher education.

Other Findings

The institute’s report also touched on faculty-administration relations. While a majority of faculty members across institution types said that their administrators consider faculty concerns when making policy, and that their administration is open about its policies, two-thirds of faculty members at both private and public institutions said they’re typically “at odds” with administrators.

Faculty at both public and private universities overwhelmingly said they believe (84 and 90 percent, respectively) that enhancing the institution’s national image is of the highest or a “high” priority at their university. Just two-thirds of faculty at four-year colleges said so. At the same time, about 8 in 10 faculty members across institutions say that promoting students’ intellectual development is as big an administrative priority.

The numbers were lower for fostering student-faculty community, however, across institution types. And faculty members at public universities were especially likely (82 percent) to say that pursuing extramural funding was of the highest priority to their administrations.

There were also questions about scholarly productivity. The CIRP construct for scholarly activity, which measures both career-spanning and recent scholarly output, shows that a greater proportion of male full professors scored “high” on the construction (62 percent) than female full professors (51 percent). The gender gap narrows but persists among all professor ranks.

Data also suggest that institutional support for professors favors junior faculty, with 45 percent of assistant professors having reported receiving internal grants for research, compared to 42 percent of associate and 38 percent of full professors.

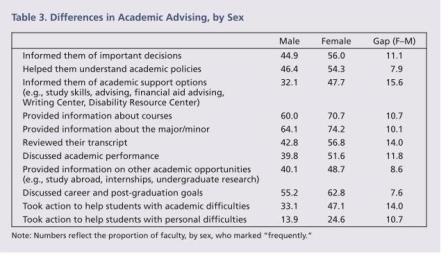

In another, optional section of survey on academic advising, completed by 7,756 faculty members at 108 institutions, significant gender gaps were observed.

Women professors reported interacting more frequently with their advisees; some 48 percent of women said they "frequently" talk to students about academic options, versus one-third of male professors, for example. They were also more likely to report going over transcripts with students and taking action to help solve academic problems.