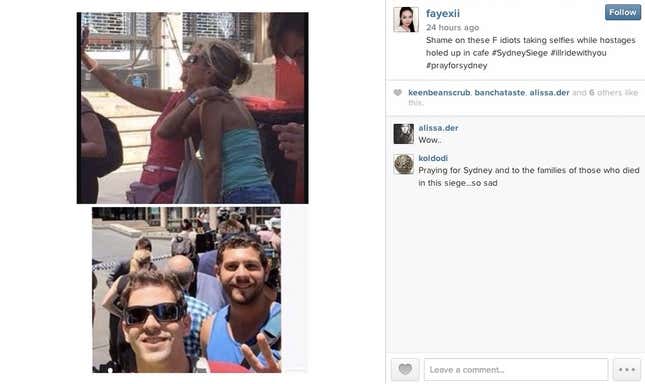

There are funeral selfies. There are Ground Zero selfies. There are Auschwitz selfies. And yesterday, during the hostage crisis in downtown Sydney, there were Sydney selfies. People were predictably outraged.

But they shouldn’t be.

Rubbernecking at disasters is an ancient sport. In 1861, spectators with picnic baskets and opera glasses gathered to watch the first major battle of the American Civil War. One woman, reported the Times of London, was heard to say, “when an unusually heavy discharge roused the current of her blood—‘That is splendid, Oh my! Is not that first rate? I guess we will be in Richmond to-morrow.’”

Visiting disaster zones after the event has a more obviously educational purpose, but it’s still rubbernecking; Mark Twain led a tour group around the abandoned battlefields of the Crimean War, you can book trips around the area devastated by Hurricane Katrina, and it’s a safe bet that people have been taking photographs of themselves standing in bomb craters in Vietnam since long before the internet was invented. We document ourselves in these places for the same reason we document ourselves at weddings and graduations; they are moments we want to remember.

So what makes disaster selfies any different? Sure, there are matters of judgment and taste; Israeli kids probably should not be taking pictures of themselves cuddling or leaping for joy in front of the gas chambers. But the truth about an unfolding disaster, be it a battle or a hostage crisis, is that for a lot of the time, nothing much is happening. Bystanders aren’t going to devote every second of their attention to watching in respectful horror. They make small-talk, call their relatives, eat a sandwich, do stretches, go to the bathroom, laugh at jokes. And they take selfies. It is no more undignified an activity; it’s just more visible.

Finally, a selfie, like any photograph, represents only a fleeting moment in time. Like the notorious picture of Brooklynites apparently relaxing on Sept. 11, 2001 while the Twin Towers burn in the background, it tells you nothing about what the people in the picture were doing outside that instant of the snapshot. Just because you mugged for the camera for a moment doesn’t mean you lacked compassion and seriousness the rest of the time. Much as they’re a symbol of shallowness, selfies also serve as the perfect channel for another very human trait—our almost universal capacity for judging one another on the basis of very little evidence.